One of Japan’s most beautiful blades is now on display, and owes its existence to some dude who just wanted to eat some potatoes and pickles.

Roughly 130 years ago, a farmer in what’s now Japan’s Toyama Prefecture was digging for potatoes when he came across an unusual stone. Even appraisers from the Osaka mint couldn’t tell what it was, and it spent the next several years being used as a tsukemono ishi, basically a large stone placed on top of vegetables as part of the pickling process.

However, this mysterious mineral was destined for greater things. In 1895, geologists from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce determined that the stone was a meteorite, which they would dub the Shirahagi Meteorite (Birch Meteorite). It was purchased by Enomoto Takeaki, a samurai who would go on to play a key role in the creation of Japan’s first modern navy and also serve as Minister of Communications, Education, Foreign Affairs, as well as two separate terms as Minister of Agriculture and Commerce.

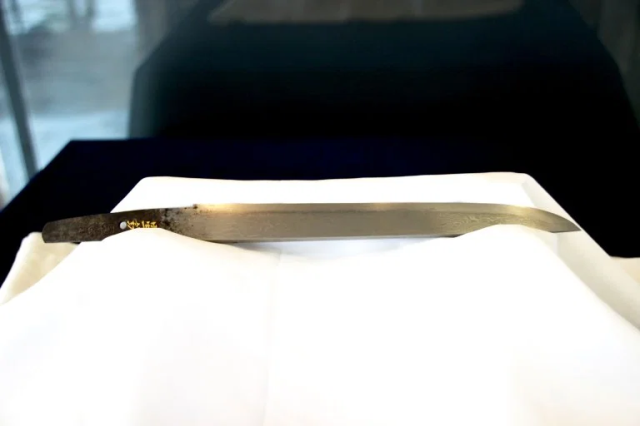

Instead of using the meteorite to make some pickles, Enomoto decided to use it to make some swords. Enlisting the services of swordsmith Okayoshi Kunimune, Enomoto commissioned five blades, two long swords and three tanto (literally “short swords,” but often closer in length to daggers) to be forged from the Shirahagi Meteorite. One of the tanto is housed at the Toyama Science Museum in Toyama City, and we took a trip to see its celestial craftsmanship for ourselves.

▼ Field reporter Meg arrives at the Toyama Science Museum

Of the five meteorite blades, collectively known as the Ryuseito (literally “comet swords”), the higher quality of the two katana was presented by Enomoto to the current crown prince of Japan, who would later become Emperor Taisho, who reigned from 1912 to 1926. The remaining four were handed down to Enomoto’s descendants. The second katana is now owned by Tokyo University of Agriculture (which grew out of an institution Enomoto founded). As for the three tanto, one is in the possession of Ryugu Shrine in Otaru, on the island of Hokkaido, one’s whereabouts are unknown, and one is the blade seen here, kept as part of the Toyama Science Museum’s collection.

The tanto isn’t on permanent display, but visitors can feast their eyes on it between now and October 14. On our visit, we also had the chance to talk to Mr. Hayashi, the museum’s astronomy curator, who told us more about what makes the blade so special.

For starters, it’s not just the origin of the metal in the Ryuseito that makes it different. Meteoric iron has a nickel content of about 10 percent, which is higher than terrestrial iron, and also less carbon. That actually makes it somewhat difficult to work with, since a lower carbon content makes the metal comparatively resistant to hardening during quenching. Because of that, the ryuseito aren’t made from meteoric iron alone, but an alloy that’s 70 percent meteoric iron and 30 percent tamahagane, the iron sand-rich metal used for regular katana.

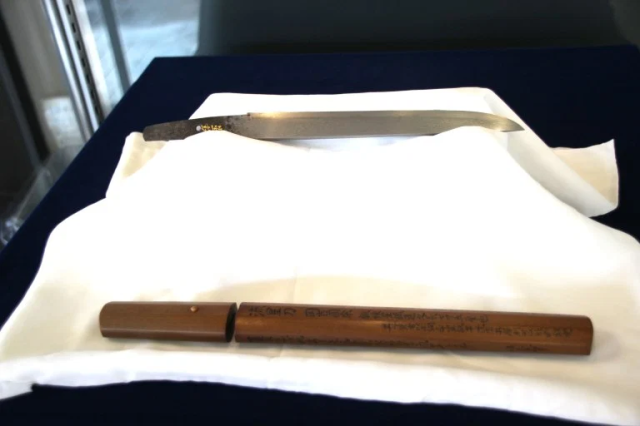

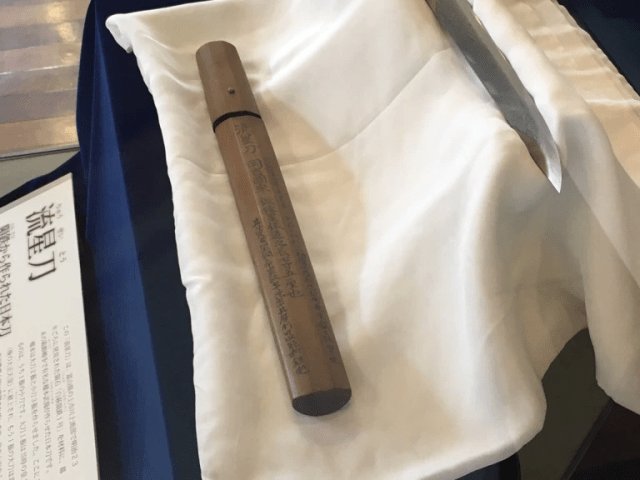

▼ The Ryuseito’s scabbard

In his journals, Enomoto says that the Ryuseito “cut well,” but Hayashi is somewhat skeptical of the claim. Even with their tamahagane content, the Ryuseito have less carbon than similar swords forged from occurring-on-earth components, and so while “meteorite sword” sounds like the sort of thing that should let you slay dragons and cleave ogres, it might not actually be the most combat effective blade, not that Hayashi and his colleagues have actually tried cutting anything with the priceless historical artifact which it’s doubtful anyone could repair (it took Okayoshi three years to complete the five swords).

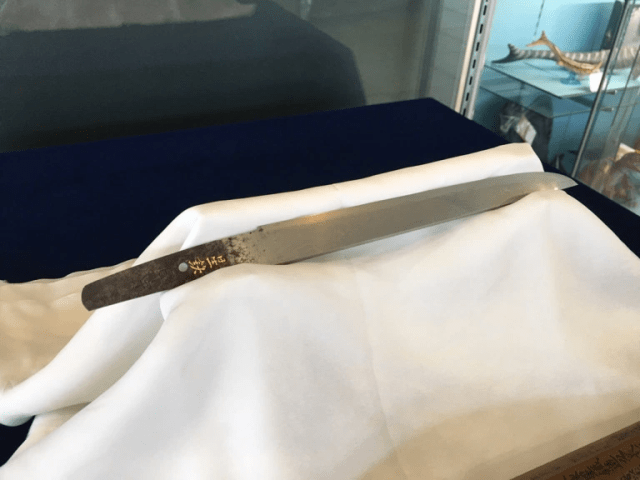

However, there is one advantage to the use of meteoric iron, which is that it produces uniquely beautiful hamon (tempering marks) along the blade’s surface. The Ryuseito had to be forged at higher-than-normal temperatures, and the final result is stark black waves that flow over the metal.

▼ Hamon totally unlike the ones we saw at the Evangelion and Katana exhibit in Tokyo

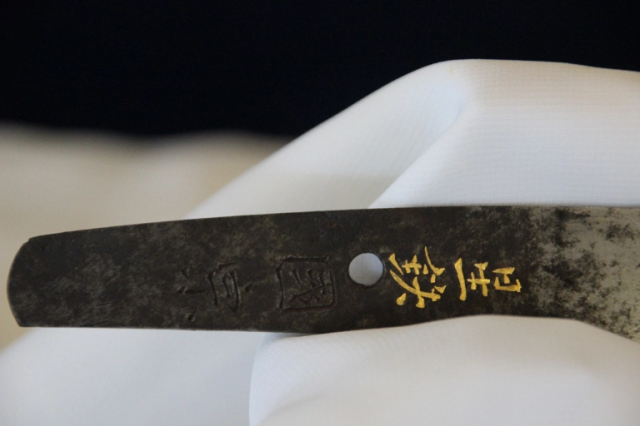

Hayashi was also able to dispel a rumor about the Ryuseito. Some people claim that unlike most notable Japanese swords, which bear the smith’s inscribed signature on their inner hilt, the Ryuseito are unmarked. That’s not the case, though, as we can clearly see the kanji for “Kunimune” engraved into the sword, as well as a solid-gold inlay reading seitetsu, or “star iron.”

So while the Ryuseito may or may not do you much good in a duel, it’s undeniably awesome to look at, and well worth stopping by the Toyama Science Museum to see if you happen to be in the area. As for the fifth Ryuseito, we’ll just have to keep our fingers crossed that it turns up, but if a farmer can find a meteorite while looking for potatoes, hopefully someday someone will find the long-lost fifth sibling sword too.

Museum information

Toyama Science Museum / 富山市科学博物館

Address: Toyama-ken, Toyama-shi, Nishinakanomachi 1-8-31

富山県富山市西中野町1丁目8-31

Open 9 a.m.-5 p.m.

Closed September 17-19

Admission 520 yen (US$4.80)

Website

Photos ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he wishes he could go back in time and tell his younger self ‘One day, you’ll write multiple professional articles about tamahagane.’”

[ Read in Japanese ]

Final Fantasy artist Yoshitaka Amano anthropomorphizes katana made from a meteorite

Final Fantasy artist Yoshitaka Amano anthropomorphizes katana made from a meteorite “Katana steel cookies” are the latest sweet treat from Japan’s samurai sword capital【Taste test】

“Katana steel cookies” are the latest sweet treat from Japan’s samurai sword capital【Taste test】 Japan’s legendary Brother Katana might not be brothers after all? Investigating the mystery【Pics】

Japan’s legendary Brother Katana might not be brothers after all? Investigating the mystery【Pics】 Demon-slaying Dojigiri, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display at Kasuga Shrine

Demon-slaying Dojigiri, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display at Kasuga Shrine Dojigiri, the millennium-old katana said to have slain a demon, is now on display in Tokyo【Pics】

Dojigiri, the millennium-old katana said to have slain a demon, is now on display in Tokyo【Pics】 McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge McDonald’s Japan releases a pancake pie for new retro kissaten coffeeshop series

McDonald’s Japan releases a pancake pie for new retro kissaten coffeeshop series More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles

Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Beautiful Sailor Moon manhole cover coasters being given out for free by Tokyo tourist center

Beautiful Sailor Moon manhole cover coasters being given out for free by Tokyo tourist center The 2023 Sanrio character popularity ranking results revealed

The 2023 Sanrio character popularity ranking results revealed One of Tokyo’s most famous meeting-spot landmarks is closing for good

One of Tokyo’s most famous meeting-spot landmarks is closing for good Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo

Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】

Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】 Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it?

Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it? Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball

Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community

We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down

Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train

Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears?

Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears? New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty Kyoto creates new for-tourist buses to address overtourism with higher prices, faster rides

Kyoto creates new for-tourist buses to address overtourism with higher prices, faster rides Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Sword of one of Japan’s last samurai discovered in house in America

Sword of one of Japan’s last samurai discovered in house in America Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】 Amazing exhibition of Japan’s legendary “cursed katana” is going on right now【Photos】

Amazing exhibition of Japan’s legendary “cursed katana” is going on right now【Photos】 Get a piece of space with this lucky bag sold by a half-man, half-alien

Get a piece of space with this lucky bag sold by a half-man, half-alien This hotel has one of the coolest katana collections in Japan, and admission is totally free【Pics】

This hotel has one of the coolest katana collections in Japan, and admission is totally free【Pics】 Mini samurai sword scissors are here to help you slice paper and plastic foes to pieces【Photos】

Mini samurai sword scissors are here to help you slice paper and plastic foes to pieces【Photos】 Japan is running out of swordsmiths, and a strict apprenticeship requirement is a big reason why

Japan is running out of swordsmiths, and a strict apprenticeship requirement is a big reason why Jewelry forged with Japanese sword-making techniques are a cut above the rest

Jewelry forged with Japanese sword-making techniques are a cut above the rest One Piece anime katanas recreated as exquisite letter openers by Japan’s swordsmith legacy heirs

One Piece anime katanas recreated as exquisite letter openers by Japan’s swordsmith legacy heirs Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo

Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo Wear a genuine piece of Japanese sword around your neck with beautiful new jewellery range

Wear a genuine piece of Japanese sword around your neck with beautiful new jewellery range Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】 Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana now on display in Tokyo【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana now on display in Tokyo【Photos】 Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade sword to be displayed in Tokyo

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade sword to be displayed in Tokyo Revealed! Japan’s top 10 handsome samurai【Photos】

Revealed! Japan’s top 10 handsome samurai【Photos】 Swords of famous samurai reborn as beautiful kitchen knives from Japan’s number-one katana town

Swords of famous samurai reborn as beautiful kitchen knives from Japan’s number-one katana town

Leave a Reply