You could say that the traditional Japanese sword, or katana, symbolizes the strength and beauty of the Japanese spirit. We see these swords quite often in comics, anime and movies, but how well do we really know the spiritual and cultural elements they embody?

To find out, we went to a true expert to learn about the fascinating and mysterious world of Japanese swords. Join us for an in-depth interview with master katana maker Norihiro Miyairi!

Miyairi was born in the city of Sakaki in Nagano Prefecture in 1956 as the first son of Kiyomune Miyairi, who was also a swordsmith. His entire family has been involved in sword-making for generations, a tradition dating back to the end of the Edo period roughly some 160 years ago, and his uncle, Yukihira Miyairi, was even designated as a living national treasure in 1963 for his sword crafting skills. So it really isn’t surprising that Miyairi chose to follow in his father’s and uncle’s footsteps and also became a katana craftsman.

Miyairi has since exhibited great talent in his chosen career, becoming the youngest swordsmith at age 39 to be ranked as a mukansa (meaning that his swords are “beyond judgement” and of such high quality that they are accepted to the annual contemporary swordsmith exhibition without screening by judges). Miyairi also counts among his numerous accomplishments creating protective short swords for three princesses of the imperial Takamadonomiya family as well as the sumo ring entrance sword for yokozuna champion wrestler Asashoryu. In 2011, he was further bestowed the honor of being designated as an intangible cultural asset of Nagano Prefecture as a master swordsmith.

But what is the world of sword making really like? We sat down with the master himself for an interview to find out:

▼ Miyairi lives in Karuizawa, a peaceful area of Nagano Prefecture rich in nature.

▼ Here’s Norihiro Miyairi, the sword maker.

RocketNews24: Why did you decide to become a swordsmith?

Miyairi: Basically because I liked it. That’s pretty much all there was to it.

RN24: Having been born into a family of katana makers, did you ever think about pursuing a different career?

Miyairi: Of course, I did. Growing up in a family of craftspeople, I liked pottery too, which I seriously considered as a career at one point. I even went around various pottery establishments across Japan, but when I really thought about it, although it was still a craft that would allow me to create something with my hands, going into pottery would have meant starting from scratch for me.

With sword making, because it was already something my family did, it wouldn’t have been a start from complete scratch. My family environment meant that I had grown up watching how swords were made, which I thought would give me just a bit of an advantage, and that seemed a good enough reason to choose sword making as my specialty. But the truth is, I would have been happy to pick up any craft.

RN24: You really liked creating and crafting things, didn’t you?

Miyairi: Well, I knew that I really couldn’t work in a typical office environment. I couldn’t integrate well with society (laughs).

RN24: Maybe artists tends to be that way in general.

Miyairi: That’s true. People in the creative world all tend to be loners, and wouldn’t do to well in society at large.

RN24: What do you think is the most difficult part about creating swords?

Miyairi: All of it is difficult. Getting the material you need for a to complete a sword, handling and working with the charcoal — it’s all difficult. We don’t have a large number of sword makers in Japan, and we also have fewer and fewer people burning and making charcoal. There are now very few people active in all the various fields necessary to carry on traditional Japanese arts and crafts, and I think it’s truly become a critical situation.

Take the charcoal, for example. I used to obtain charcoal from Iwate Prefecture in the past, but a lot of the establishments with kilns were destroyed by the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 and so they became unable to produce charcoal. There has also been the problem of fewer young people taking up the trade in recent years. All of this combined to almost cut off our supply of charcoal, and at one point there were quotas on how much charcoal we could buy – just 20 to 30 bales per person. We can’t do our work without charcoal, so it really made things difficult for us for a time.

But through the network of people I know, I’ve been able to find a suitable kiln and also someone able to produce the charcoal for me locally, and I’m now able to get by. It’s a tough time for craftspeople now because there’s so much they have to manage — there’s a lot to be concerned about other than just creating things, like securing the necessary fuel.

RN24: We’ve heard that it’s very difficult to make a living as a swordsmith. Is this true?

Miyairi: Well, there are some young swordsmiths who have recently gone out on their own, but with the economy what it is these days, many of them struggle to earn a living and are forced to give up their craft.

RN24: So it is quite difficult, after all?

Miyairi: Yes, I have to say it is. If you think about it, swords are objects people don’t really need. By comparison, pottery, for example, is something you can actually use. You wouldn’t be using a katana in this day and age, would you?

RN24: That’s true. You wouldn’t use swords today to cut people down…

Miyairi: The bottom line is, swords are weapons. That’s why we swordsmiths need to be approved by the Japanese government before we can make swords. To obtain that approval, you need to first apprentice with a master swordsmith for at least five years and then complete a practical katana making training course conducted by the government’s Agency for Cultural Affairs. Only then are you allowed to make swords.

There are plenty of aspiring swordsmiths who begin this process but find they’re unable to complete it because of the difficulties. And even those who pass the training and become licensed often discover that they can now make swords but aren’t able to sell enough of them to make a living and are forced to give up swordmaking as an occupation. I think the ones who really love the craft, though, are able to keep their motivation up and stick with it, regardless of how little money there is to be made. But it does mean that there are fewer and fewer truly capable people in the trade.

▼Here Miyairi shows us a sword he is repairing for a client.

▼ It was quite heavy in our hands!

▼ We were able to see our faces clearly reflected in the blade! We were impressed with how much more beautiful an actual sword looked compared to what we’d seen in books or movies.

RN24: So, many people eventually give up being swordsmiths even though they get licensed?

Miyairi: That’s right. Like I said, they simply can’t earn enough. Using pottery as an example again, a work of pottery can be sold as a product soon after it’s taken out of the kiln. But with swords, after you make the actual sword, it still has to go through various processes: the saya (scabbard) and the habaki (the metal wedge fitted on the blade that keeps the sword securely in the scabbard) have to be made, and the sword also requires expert polishing (togi), all of which has to be done by different craftspeople. And of course, each process costs money.

If you outsource to have the saya and habaki made and the polishing done by expert craftsmen, it costs about 500,000 yen (US$4,178), and for young swordsmiths, they’re lucky if they can get 1,000,000 yen ($8,358) for a sword. And you still have all the initial costs of the raw material and fuel and such, that have to be accounted for. When you take all those costs into consideration, there isn’t much left for the swordsmith at the end of the day.

So, what happens is, you make your swords, but they don’t make enough profit for you to make a living, and you’re caught in a vicious cycle until eventually you can’t keep going on and you’re forced to find another job. It’s really tough.

RN24: Swords were originally created as weapons with which to cut people. Now, we look at swords and appreciate their beauty and the sense of the Japanese spirit they inspire in us, so they’ve probably taken on a different purpose. Are swords today different from what they were in the past?

Miyairi: No, fundamentally, they’re not different. Swords have traditionally been made as weapons and also as works of art to be admired for their beauty, depending on their intended purpose. Today in Japan, we only make swords for artistic purposes; otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to obtain approval from the government. Also, most famous swords which are considered meitou (名刀, literally “excellent sword”) are swords that were created as works of art.

RN24: Does that mean famous meito swords don’t cut very well?

Miyairi: Well, I wouldn’t know since I’ve never actually used them, but they are genuine swords, so there’s no doubt you can use them that way. Now, how strong the blades on such swords would be, I can’t say, as I haven’t tried using them.

RN24: Why is it that so many famous swords from so long ago are still in existence today?

Miyairi: That’s because the daimyo (feudal lords in the age of the samurai) families protected and took care of the swords. Swords worthy of national treasure status would all have been valued and treated with extreme care by the families that owned them. Just to give you some perspective, you can find references to the price of swords in written material going back to the Muromachi period in the 1470s, in which a meitou quality sword was valued at 10,000 hiki (the currency of the Muromachi Period) and a regular sword at 100 hiki.

So even back then, a meitou was worth 100 times a regular sword. That would roughly translate to a 1,000,000 yen ($8,358) sword and a 100,000,000 yen ($835,800) sword today. That’s how different their values were.

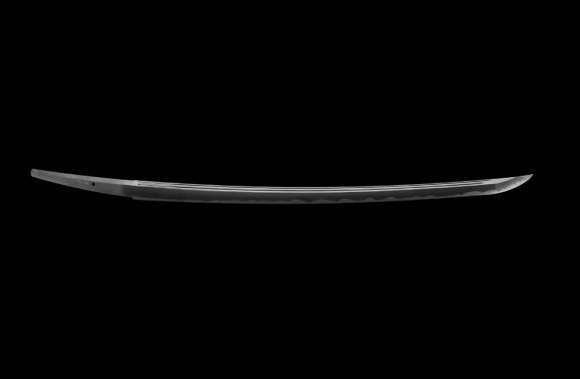

▼A tachi sword that Miyairi made in 2009:

▼ The patterns on the blade that look like thunderclouds are gorgeous!

RN24: What would you say is the proper way to appreciate Japanese swords?

Miyairi: Just looking at them isn’t really enough. Whether you’re Japanese or from abroad, there’s some studying required. As with many other objects, there are different ranks of swords. You need an eye for distinguishing superior swords from those of lesser quality, and for that you need to do a fair amount of studying.

RN24: There are many different types of weapons around the world. What do you think makes Japanese swords so deeply appealing?

Miyairi: If you look around, you can find swords in every part of the world. But of all the different types of swords in the world, the Japanese katana is probably the only kind of sword that is appreciated for the beauty and artistry of the steel itself.

Swords from other countries are ornately decorated and valued for carvings or jewels added to the blade, but Japanese swords are valued for the material they are made of. I think that’s the biggest difference. Historically, one of the three sacred treasures (sanshu no jingi) of Japan has been a sword, and the katana with its bright, shiny surface has traditionally been created as a kind of talisman, playing an important role in the culture and spirit of the Japanese people.

And I think a major reason the Japanese sword came to be acknowledged for its artistic value is because the skill of polishing, or kenma as it’s called, has also existed as a well-established craft for a long time. Now, I’m not sure if this is a perception limited to Japan, but it seems to me that we tend to think of steel as something just plain black and metallic.

But if you look back to written sources from the Kamakura Period (1180s to 1330s) or Muromachi Period (1330s to 1570s), you see descriptions of swords in colors such as black, white, red, blue. The fact that such colors are mentioned means that they had advanced polishing techniques which they used on the swords. In other words, they had the skill to distinguish between all of these different colors of steel. I think the availability of such fine polishing techniques had a great deal to do with why the Japanese sword has been loved and cherished to this day.

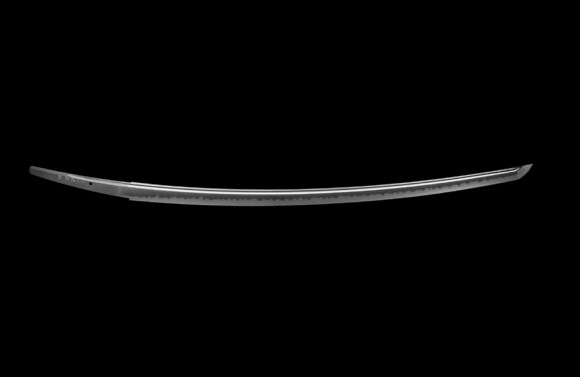

▼ The tachi sword Miyairi made when he was designated an intangible cultural asset of Nagano Prefecture:

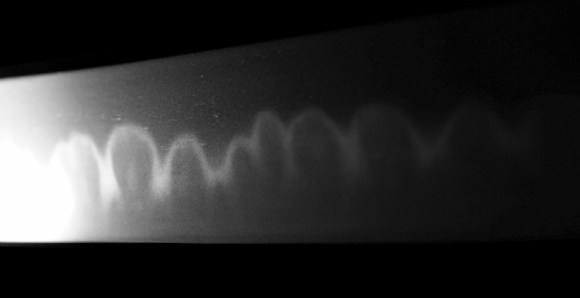

▼ The pattern of the hamon (temper lines) which looks like clove fruits strung together is characteristic of the Bizen-Den division of sword making.

RN24: We heard that when you were an apprentice, you went to study under Masamine Sumitani, despite opposition from your uncle, Yukihira. What were your thoughts at that time? What prompted you to leave your home and study elsewhere?

Miyairi: I really loved Master Sumitani’s work. But I wouldn’t have been able to apprentice with him if it hadn’t been for certain circumstances coming into being quite by coincidence. First, in the November before I graduated from college, Uncle Yukihira passed away. Then, in February the next year, Kanzan Sato, who was a sword appraiser and the leader figure of the The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords at the time, and who was also opposed to my apprenticing with Sumitani, also passed on.

It was purely by coincidence that the two people opposed to my learning the craft away from my family passed away around that time and I was able to apprentice with Sumitani. In that way, I guess I feel a kind of connection with Master Sumitani, that it was somehow meant to be. I really liked Sumitani’s personality and his work and so asked him to take me on as an apprentice.

RN24: And there was a lot of opposition to your decision at the time?

Miyairi: Practically everyone objected. I had no one on my side, although I guess that was to be expected.

RN24: And yet you stuck with your decision, despite all this opposition. You really must have wanted to learn from Sumitani.

Miyairi: Yes, I did. Master Sumitani made swords with the heart of an artist, not just the techniques of a craftsman. He wrote superb calligraphy and drew beautifully. He was amazingly talented in most things he did, and he just seemed a wonderful mentor to study under. He wasn’t just about sword making; he was cultured and knowledgeable in a wide range of fields.

And all of that contributed to his creativity. The way he worked and the works he produced were innovative, which is what made it all so attractive. In the end, it’s about what you want to make, and you don’t need to be concerned with what other people say or do. That’s how I became Sumitani’s apprentice.

RN24: Why was everyone around you so opposed to your apprenticeship?

Miyairi: The world of swordmaking is very conservative. Like in the world of sumo, we cling fiercely to the idea of the close-knit, family based group. There are currently three main schools of swordmaking in Japan: the Miyairi, the Gassan and the Sumitani, and even today, if a direct heir to one of the schools were to try to study under a different school, there would be stiff opposition.

RN24: Had something like that been done in the past?

Miyairi: Never!

RN24: So what you did really was groundbreaking.

Miyairi: Well, it’s something that simply wouldn’t have been allowed under ordinary circumstances.

RN24: How did Master Sumitani deal with the situation?

Miyairi: Oh, he accepted it. The very fact that I asked to study under him meant that the Miyairi school held his skills in high regard, so it didn’t hurt him at all.

▼The “Shige-Bachiru-Tsuka-Saya-no-Tosu” made by Miyairi — the short sword is based on the “Ryokuge-Tsuka-Saya-Bachiru-Kinkazari-no-Tosu“, one of the treasures of the famous Shosoin Museum. Miyairi has also done work restoring valuable tosu swords stored in the Shosoin.

▼Tosu are short swords that were used in the Nara Period (early to late eighth century) adorned with various outer decorations and carried by aristocrats of the time as talismans.

RN24: How would you like future owners of your work to use the swords?

Miyairi: If the sword is for the family, I hope it will be cherished and passed through the generations as a family talisman.

RN24: By talisman, you mean something that will keep the family safe from harm?

Miyairi: Exactly. The sword is one of Japan’s traditional three sacred treasures, in addition to the “magatama” bead and the mirror, and there’s also a custom in the Imperial family where a sword is presented by the emperor in a ceremony called the Shiken no Gi (literally, “sword gifting ceremony”) when a new baby is born into the family. The purpose of that ceremony is to wish for the healthy growth of the newborn child.

RN24: In an ideal world, how would you like the culture and knowledge of swords to spread in Japan in the future? For example, would you want all households in Japan to have their own talisman sword?

Miyairi: I would want as many people as possible to be interested in swords. Also, unless young swordsmiths are able to make a decent living, we won’t have the next generation of sword makers to carry on the trade no matter how many apprentices we train, so I hope we can create a system to better support young sword craftsmen and hopefully see an increase in the overall number of katana makers.

RN24: A system to support sword makers?

Miyairi: Yes. Ideally, it would be great if the national government’s system could be adapted for that purpose, but if that’s difficult, maybe opening channels abroad can help improve the situation for young swordsmiths. To that end, it would be good if we could think internationally and promote the trade of sword-making to the world.

▼Miyairi personally showed us the process called matome (literally, “putting things together”), in which the steel to be used for the sword is fixed into a square shape.

▼The fire sparks reach temperatures of about 1,300ºC (2,372ºF). It was incredibly hot just watching from close by.

RN24: Do you ever receive orders from overseas clients?

Miyairi: Yes, I do.

RN24: And what kind of clients are they?

Miyairi: Many of them are katana fans from foreign countries.

RN24: Which countries are they from?

Miyairi: In my case, many are from Sweden and Denmark – a good number are from Scandinavia.

RN24: So, katanas are popular in Scandinavia?

Miyairi: There just happens to be a person in Scandinavia who loves katanas and has set up a group, a kind of society you could say, for katana enthusiasts. I’ve received several orders through that person.

RN24: Are overseas fans mainly collectors?

Miyairi: Yes, I’d say they are.

RN24: Do such fans typically decide they want to own a sword after learning about the Japanese cultural background behind it?

Miyairi: These are people who have visited Japan and taken time to study about swords. They know more about appreciating and evaluating swords than most average Japanese. They’ve also taken the initiative to start their own group back home and learn about katanas.

▼ Here are more pictures of the master at work.

▼ A machine hammer is used to firmly strike the steel into shape.

RN24: Swords have recently gained some popularity among young women due to an online game called Token Ranbu (literally, “wild dancing with swords”), in which swords appear as anthropomorphisized human characters. How do you feel about such social phenomena?

Miyairi: I think it’s a good thing for swords to gain attention and wider recognition. If even a few people can go on from there to take a serious interest in swords and study them, then that’s great. I guess it’s a bit like sushi; there’s traditional Japanese sushi, and when it’s taken out of Japan, it changes into different kinds of sushi around the world. I think that’s fine.

Naturally, there will be people who come to Japan and want to have traditional, authentic Japanese sushi, and people might end up being surprised by how good it is. In that way, if a video game is what gets people to take notice of swords, then I’m sure it’s a good thing.

RN24: Have you ever played any video games?

Miyairi: No, I never have.

RN24: Do you watch any television in your daily life?

Miyairi: Maybe just the news on (Japan’s national public broadcasting channel) NHK . I don’t watch variety shows and such.

RN24: Speaking of entertainment, do you ever watch movies?

Miyairi: Only very rarely.

RN24: What do you do to relax?

Miyairi: Enjoy drinks in my living room, I guess.

RN24: Wow!

Miyairi: Why so surprised?

RN24: Because it seems like you’re so far removed from typical mundane and earthly wants and desires…

Miyairi: Well, living here, you don’t really need much.

RN24: You don’t get stressed?

Miyairi: No, I don’t. There’s not much I want. In a city like Tokyo, though, I’m sure there would be plenty of temptations.

RN24: There’s nothing you particularly want?

Miyairi: Hmm…something I want? No, not at the moment!

▼ Here’s the steel after the matome process. The pieces really are square!

In the next part of our interview, we asked Miyairi some questions from our readers.

RN24: What are the basic ingredients used to make a sword?

Miyairi: The basic ingredient is tamahagane (literally, “round steel”; a type of high quality steel made from iron sand). But if you use the same ingredient, you end up making the sword the same way, so if you want to create something new, you have to think of original ingredients to use.

RN24: What kind of new ingredients, for example?

Miyairi: I’ve been using a type of steel called zuku (pig iron) that has a higher carbon content than tamahagane.

▼Depending on the work to be done, Miyairi sometimes spends the entire day in the workroom. It can be a lonely world with just you and the sword.

▼During the process called tanren (literally, “to train and harden”) where the steel is struck to remove impurities, the curtains are shut to keep the room completely dark. With all the curtains closed, the temperature in the room during the Summer can reach above 40°C (104°F), creating a sauna-like environment.

▼The reason the room is kept dark is to better judge the color of the flames.

The following question was also from one of our readers.

RN24: If you were allowed to make a sword with any single swordsmith from history, who would you choose?

Miyairi: Hmm…that’s difficult to answer. Every sword has its own beauty, so I don’t think I could choose one swordsmith in particular.

RN24: Do you have any ingredients that you want to get hold of right now?

Miyairi: As a matter of fact, I do. The term is a bit technical, but I really want some hocho-tetsu (literally, “knife steel”). It’s a soft type of steel you get from removing as much carbon as possible from zuku. That’s what I want right now.

RN24: Is there no one who can make this hocho-tetsu?

Miyairi: The skill to produce it doesn’t exist.

RN24: Is that so?

Miyairi: At present, the skill doesn’t exist, and there’s no one to make it, either.

RN24: Is there actually a sword made from hocho-tetsu?

Miyairi: Hocho-tetsu by itself can’t be made into a sword. You have to process it by mixing it with various ingredients in order to use it for a sword.

RN24: What would be different about a sword made with hocho-tetsu?

Miyairi: The view – what you see in the sword – would be different. There are three important points to see in a sword. The first is the shape, or form, of the sword. The second is what we call the jigane, the pattern or “view”, if you will, that appears on the material of the sword as a result of the folding back and tanren striking process. The third is the hamon, or temper lines that appear at the border where materials of different consistencies come together on the blade. These lines create various patterns that may look like lightning or clouds and also give the sword a unique “view”. These are the points you want to look for in a sword, and the beauty you see in each of them will vary greatly depending on the material used.

▼ Here we have pictures of Miyairi showing us the polishing process.

▼ The swordsmith does some light polishing, but the sword is taken to a specialist polisher for the final polish.

RN24: What do swords mean to you?

Miyairi: In a way, swords are like small copies of myself, since I put my whole being and soul into making them.

RN24: Does that mean the person you are when you’re making the sword is reflected in the katana?

Miyairi: That’s right, because I put a lot of thought into what I want to do with each sword.

RN24: So, the environment you’re in and your state of mind–

Miyairi: –influences the result you get in the finished sword. That’s right.

RN24: And now, we’ve come to our final question. What are your dreams for the future?

Miyairi: In the world of katanas, it’s still a matter of how your swords measure up to old swords from the past. Contemporary swords are judged on how their quality compares to that of ancient swords. Simply for that reason, I want to make swords just as good or better than the valued old katanas. I guess creating a sword comparable in quality to one of the famous meitou swords would be my dream.

RN24: And these swords would be judged by specialist appraisers?

Miyairi: Yes, that would generally be the case, but in the end, I have to trust my own eyes the most. That’s why I try to see as many objects of fine quality as possible, to see items considered to be first-rate whenever I have the chance. You could say that appraisers can only see what’s on the surface, while we have the advantage of knowing all the material that went into making the object, which gives us a different perspective and allows us to look a little bit deeper inside than the appraisers.

RN24: So, your dream would be to make a sword that you yourself are satisfied with and that rivals the quality of historic swords?

Miyairi: Yes, it would. I may never be able to accomplish it, but I certainly want to get as close to it as possible. That’s my dream.

RN24: Thank you so much for sharing your time with us.

– – –

So, that concludes our interview with Norihiro Miyairi. We hope you found it educational as well as interesting. We still have more photos to share with you below, but what impressed us most during the interview was Mr. Miyairi’s stoic professionalism and dedication, and most of all, the kindness he showed us. Not only did he take the time to give us the interview we requested, he was extremely welcoming and courteous to us, as if we were special guests rather than probing reporters.

He carefully explained to us each step involved in sword making, and after we were done with the interview, he even drove his car to lead us on the right way back. It almost felt like we were being taken care of by family, and we were truly grateful for his warmth.

After meeting with Mr. Miyairi, we left feeling that someone who has seriously strived for excellence in something, whatever the field, probably learns to be kind to others.

To get where they are now, masters in any field will have had to have support from many people and will know how valuable kindness from others can be. Perhaps this allows them to always be grateful for what people have done for them and to be kind to others in return. We found Mr. Miyairi to be an awesome, warm-hearted artisan and human being who made us want to be like him when we reached his age. Thank you again, Mr. Miyairi for an insightful as well as informative experience!

And now, we have some pictures of our reporters trying their hands at some of the steps in sword making. Enjoy!

▼ We experienced a little of the “polishing” process.

▼ You have to seat yourself in a unique position, and you may hurt your knees if you’re not used to it.

▼ This is the low stool you sit on.

▼ It’s very hard to keep your balance in this position!

▼ You’re supposed to place your weight on your right leg.

▼ Yoshio here seems to be faring better now, but keeping this position for a long time would definitely be quite uncomfortable.

▼ We also tried the sumi-kiri (charcoal cutting) process, where you are supposed to cut the charcoal into pieces of the exact same size. This is the first step that aspiring swordsmiths learn, and it usually takes about three years for them to become able to cut the charcoal quickly and cleanly.

▼ Miyairi tells us to be careful, as some apprentices crack their nails with the knife. This completely frightens our poor reporter Yoshio.

▼ It’s near impossible for us to cut the charcoal cleanly. Amazingly, swordsmiths usually complete this task in a dark workroom with the lights turned off!

▼ Burns are part of the daily routine, and Miyairi says his burns seem to be healing faster these days. All the small charcoal particles in the air can also frequently hurt your throat. Not surprisingly, when our reporter blew his nose after the interview, the tissue became black with soot.

▼ Miyairi’s hands are sometimes called “God’s hands”.

▼ It’s amazing to think that these hands have produced numerous beautiful sword masterpieces!

▼ Miyairi says that a swordsmith is at his most productive in his late 50s to early 60s. All his life experiences play an important part in forging the sword.

▼Here’s a video summarizing our fascinating visit and interview with Miyairi. Check out all the steel-striking action!

We’d like to end with one final message from Mr. Miyairi to our readers: “The more drawers you have access to, the more ways you’ll have to apply your talents and create something meaningful. And the more failures you’ve experienced, the more drawers you’ll have. So don’t be afraid to face challenges and fail many times over.”

Wise words indeed.

Reference: Facebook (The Norihiro Miyairi Supporters’ Group)

Original report by: Daiichiro Tashiro

Photos © RocketNews24 except where otherwise noted

[ Read in Japanese ]

Japanese samurai sword ice cream crafted by master swordsmith from famous katana town of Seki

Japanese samurai sword ice cream crafted by master swordsmith from famous katana town of Seki Cruel angels, beautiful blades: The amazing sword of the Evangelion and Katana exhibition【Photos】

Cruel angels, beautiful blades: The amazing sword of the Evangelion and Katana exhibition【Photos】 “Katana steel cookies” are the latest sweet treat from Japan’s samurai sword capital【Taste test】

“Katana steel cookies” are the latest sweet treat from Japan’s samurai sword capital【Taste test】 Oddly-satisfying video shows katana warping and bending in water as it is forged

Oddly-satisfying video shows katana warping and bending in water as it is forged Cool housewarming bonus: free Japanese katanas, potentially carved by a master craftsman

Cool housewarming bonus: free Japanese katanas, potentially carved by a master craftsman Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Skyscraper sized Pokémon cards to appear in Tokyo all year long in Tocho projection mapping event

Skyscraper sized Pokémon cards to appear in Tokyo all year long in Tocho projection mapping event Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Clever and cute cat keyhole bra is only one-fourth of lingerie set’s feline charms 【Photos】

Clever and cute cat keyhole bra is only one-fourth of lingerie set’s feline charms 【Photos】 Beautiful blue apple jam is taking the Japanese internet’s breath away!

Beautiful blue apple jam is taking the Japanese internet’s breath away! Japanese Twitter user shares a genius-level tip for drawing manga characters in skirts【Pics】

Japanese Twitter user shares a genius-level tip for drawing manga characters in skirts【Pics】 566 million yen in gold bars donated to Japanese city’s water bureau

566 million yen in gold bars donated to Japanese city’s water bureau The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】 Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo

Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo Want to become a swordsmith? Apprenticeship opens in Japan, but the fine print might shock you

Want to become a swordsmith? Apprenticeship opens in Japan, but the fine print might shock you You can get a custom-made katana and a tax discount by donating to this Kyoto city【Photos】

You can get a custom-made katana and a tax discount by donating to this Kyoto city【Photos】 Chop up paperwork with katana scissors inspired by the swords of Oda Nobunaga and other samurai

Chop up paperwork with katana scissors inspired by the swords of Oda Nobunaga and other samurai Authentic Japanese sword letter openers available through crowdfunding

Authentic Japanese sword letter openers available through crowdfunding Mini samurai sword scissors are here to help you slice paper and plastic foes to pieces【Photos】

Mini samurai sword scissors are here to help you slice paper and plastic foes to pieces【Photos】 Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】 Genuine Muramasa blade and Muromachi katana on display at Tokyo’s Touken Ranbu store【Photos】

Genuine Muramasa blade and Muromachi katana on display at Tokyo’s Touken Ranbu store【Photos】 “2D vs. Katana” exhibition shows off recreations of swords from anime and video games in Osaka

“2D vs. Katana” exhibition shows off recreations of swords from anime and video games in Osaka Crowdfunded samurai sword-inspired kitchen knives now available for general sale

Crowdfunded samurai sword-inspired kitchen knives now available for general sale Swords of famous samurai reborn as beautiful kitchen knives from Japan’s number-one katana town

Swords of famous samurai reborn as beautiful kitchen knives from Japan’s number-one katana town Elderly anime fan allegedly threatens to kill man who complained about loud TV with fake katana

Elderly anime fan allegedly threatens to kill man who complained about loud TV with fake katana Fight like a ninja in a samurai town, with sword-fighting experience at Kyoto Toei movie studio park

Fight like a ninja in a samurai town, with sword-fighting experience at Kyoto Toei movie studio park We get a haircut by a stylist who cuts with katanas and fire at “Samurai Salon” in Spain

We get a haircut by a stylist who cuts with katanas and fire at “Samurai Salon” in Spain