Want to make katana for a living? Hope you don’t mind not getting paid a single yen for the next five years.

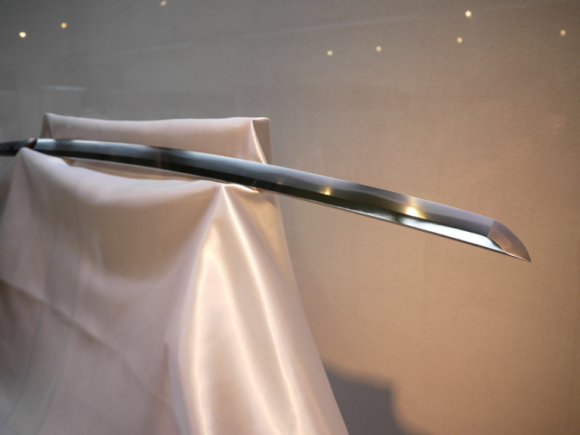

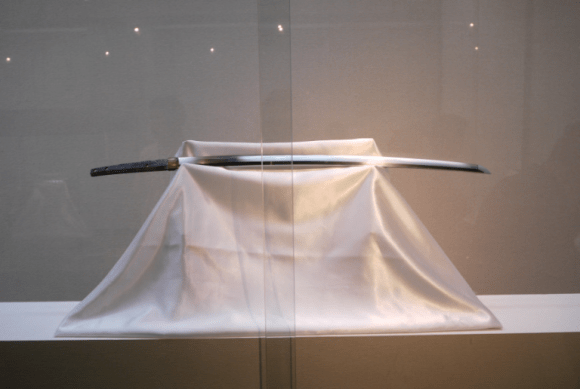

Although it might sound unusual for artifacts with a centuries-long history, swords are currently in vogue in Japan. Museum exhibitions of historically significant katana have been attracting large, enthusiastic crowds in recent years, but the blades’ surging popularity is yet to solve a few problems.

In 1989, the Japanese Swordsmith Association counted 300 registered swordsmiths in the country. Not 20 years later, that number has been nearly cut in half, with only 188 smiths currently registered, and their average age rapidly increasing.

Swordsmithing isn’t just an industry, it’s also part of Japan’s cultural heritage. To preserve the craft, Tetsuya Tsubouchi, one of the Japanese Swordsmith Association’s directors, says two things have to be done. First, new swordsmiths have to be trained and certified to replace the craftsmen who’re retiring or otherwise being lost to old age, but there are some major hurdles in the way.

Not just anyone start hammering away and producing swords for sale in Japan. Practitioners are required to first serve as an apprentice under a registered swordsmith for a period of five years. These apprenticeships are unpaid, meaning that blacksmithing could be considered one of Japan’s harsh “black enterprises.” Those who want to complete the training must either burn through savings they amassed working in another field (before quitting that job to start their apprenticeship) or rely on financial support from their families. But while Japanese parents are generally willing to invest in their children’s education, it’s pretty difficult to convince Mom and Dad to cover all of your living expenses for a half-decade so that you can take a shot at making it in as niche an industry as swordsmithing. As a result, Tsubouchu says that though there’s actually been a recent uptick in apprenticeship applications, very few apprentices actually make it to the end of their five-year training period.

Even if they do complete their apprenticeship, prospective smiths still have to pass a national certification test, which takes place over a period of eight days. The test is offered only once a year, so if you fail, you’ve got a long wait until you get to take another swing at it. Oh, and once that’s all done, the estimated cost to set up a swordsmithing business of your own is 10 million yen (US$91,000), an amount of seed money that’s kind of hard to scrape together when your last paycheck was five years ago.

The other thing the industry needs, Tsubouchi says, is new customers. Collectors of art and antiquities have long been happy to buy and sell historical pieces, but a demand for preexisting blades isn’t creating much work for present-day smiths. What they need are people who’re interested in buying freshly forged swords, especially since they can7t just sell batches to the local samurai warlord like their predecessors in the feudal era did.

Luckily, a surge in popularity among sword-carrying anime and video game characters (some of which are actually swords themselves), as well as cosplayers dressed as those characters, has raised awareness of katana among young people, especially Japanese women, who’ve been showing a renewed interest in Japanese history in general over the past decade. Tsubouchi also points to collaborative efforts such as exhibitions that combine anime and katana aesthetics, such as a popular traveling display of swords inspired by the Evangelion franchise.

Tsubouchi also sees potential in the fact that rekijo, as Japan calls women with an interest in samurai history, range in age from teens up through women in their 30s and 40s. The director points out that in the past, it was often older, married men who wanted to buy katana to keep as family heirlooms, only to have the idea shot down as overly extravagant by the women of their household. But if both husband and wife, and maybe their daughter too, are keen on having a sword on display in the home, that purchase becomes a lot more justifiable.

The hope, Tsubouchi says, is not necessarily for new customers to convince people to buy ultra-premium pieces, but rather to cultivate a market for Japanese swords that are within the budget of even people who aren’t wealthy art collectors. He even muses about the possibility of reestablishing the largely forgotten custom of omamorigatana, in which swords were given as a good luck charm commemorating auspicious occasions such as births and marriages.

Still, with Japan placing so much importance on financial stability, it’s going to be an uphill battle encouraging people to seriously consider a career in swordsmithing, at least until there’s some solid evidence that all those people lining up to see swords at the museum would be genuinely willing to buy one for themselves.

Source: Yahoo! News Japan/Oricon News via Otakomu

Images ©SoraNews24

Want to become a swordsmith? Apprenticeship opens in Japan, but the fine print might shock you

Want to become a swordsmith? Apprenticeship opens in Japan, but the fine print might shock you Dojigiri, the millennium-old katana said to have slain a demon, is now on display in Tokyo【Pics】

Dojigiri, the millennium-old katana said to have slain a demon, is now on display in Tokyo【Pics】 Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo

Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】 Japan’s legendary Brother Katana might not be brothers after all? Investigating the mystery【Pics】

Japan’s legendary Brother Katana might not be brothers after all? Investigating the mystery【Pics】 Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Seaside scenery, history, and so many desserts on Yokohama’s Akai Kutsu【Japan Loop Buses】

Seaside scenery, history, and so many desserts on Yokohama’s Akai Kutsu【Japan Loop Buses】 Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day

Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it

Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it The 2023 Sanrio character popularity ranking results revealed

The 2023 Sanrio character popularity ranking results revealed Should you add tartar sauce to Japanese curry rice? CoCo Ichi makes diners an unusual offer

Should you add tartar sauce to Japanese curry rice? CoCo Ichi makes diners an unusual offer Starbucks Japan releases new mugs and gifts for Mother’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new mugs and gifts for Mother’s Day Smash Bros. director Sakurai stabs Kirby in the face, has delicious justification for it

Smash Bros. director Sakurai stabs Kirby in the face, has delicious justification for it Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】 Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade sword to be displayed in Tokyo

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade sword to be displayed in Tokyo Samurai sword hunt begins as storm washes away blacksmith’s warehouse in Gifu Prefecture

Samurai sword hunt begins as storm washes away blacksmith’s warehouse in Gifu Prefecture Demon-slaying Dojigiri, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display at Kasuga Shrine

Demon-slaying Dojigiri, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display at Kasuga Shrine Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana now on display in Tokyo【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana now on display in Tokyo【Photos】 “Katana steel cookies” are the latest sweet treat from Japan’s samurai sword capital【Taste test】

“Katana steel cookies” are the latest sweet treat from Japan’s samurai sword capital【Taste test】 Japanese samurai sword ice cream crafted by master swordsmith from famous katana town of Seki

Japanese samurai sword ice cream crafted by master swordsmith from famous katana town of Seki This hotel has one of the coolest katana collections in Japan, and admission is totally free【Pics】

This hotel has one of the coolest katana collections in Japan, and admission is totally free【Pics】 Genuine Muramasa blade and Muromachi katana on display at Tokyo’s Touken Ranbu store【Photos】

Genuine Muramasa blade and Muromachi katana on display at Tokyo’s Touken Ranbu store【Photos】 Katana of four of Japan’s greatest samurai turned into gorgeous scissors

Katana of four of Japan’s greatest samurai turned into gorgeous scissors Japanese city offering authentic handcrafted swords in exchange for “tax” payments

Japanese city offering authentic handcrafted swords in exchange for “tax” payments Mini samurai sword scissors are here to help you slice paper and plastic foes to pieces【Photos】

Mini samurai sword scissors are here to help you slice paper and plastic foes to pieces【Photos】 Want to see a katana being made from scratch? Of course you do!【Video】

Want to see a katana being made from scratch? Of course you do!【Video】 Scholars confirm first discovery of Japanese sword from master bladesmith Masamune in 150 years

Scholars confirm first discovery of Japanese sword from master bladesmith Masamune in 150 years Final Fantasy artist Yoshitaka Amano anthropomorphizes katana made from a meteorite

Final Fantasy artist Yoshitaka Amano anthropomorphizes katana made from a meteorite

Leave a Reply