Number of hochi akiya continues to rise.

So let’s start things off with a quick little Japanese vocabulary lesson about the word akiya. A combination of aki, (“empty”) and ya (“house”) akiya refers to a home with no regular resident.

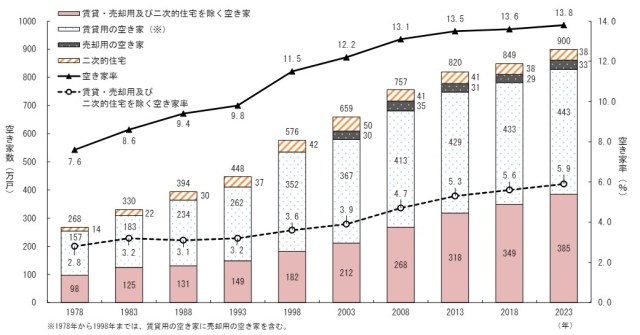

Despite having some very high population densities in its biggest cities, Japan also has a lot of akiya. This week, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications released the results of its Housing and Land Statistical Survey, which it conducts every five years, and determined that there are currently about 9 million akiya in Japan. Those nine million akiya represent an increase of roughly 510,000 since the last survey five years ago, and are double the amount from 30 years ago.

The more startling statistic from the report, though, is that 3.85 million of those akiya are hochi akiya, or “abandoned homes,” which account for 5.9 percent of housing units in Japan. While akiya can include things like vacation houses which don’t have anyone staying there for most of the year, or completed homes that are on the market but haven’t been sold yet, hochi akiya are specifically homes that have no resident and aren’t available for sale or any other use. The number of abandoned homes in Japan increased by 36 million since the last survey in 2018, and has more than doubled since 1998.

● Number of abandoned homes in Japan

1978: 980,000

1983: 1,250,000

1988: 1,310,000

1993: 1,490,000

1998: 1,820,000

2003: 2,120,000

2008: 2,680,000

2013: 3,180,000

2018: 3,490,000

2023: 3,850,000

▼ Graph showing number of akiya in Japan, composed of abandoned houses (pink), homes for rent (white with dots), homes for sale (black with dots), and secondary-use/vacation homes (striped). For each category, the number of homes, in units of 10,000, is written in its section of the by-year bar

So how did this situation come about? The most obvious answer is Japan’s aging population and declining birthrate. Fewer people mean less total demand for housing, and smaller families mean less demand for homes from generations back that were sized for parents, multiple kids, and maybe even grandparents living together under the same roof.

The last few generations in Japan have also seen a continuing migration of the population away from rural areas and towards large cities. The prefectures with the largest percentages of abandoned homes, all over 10 percent, are all mostly rural, and it’s likely that many members of the last few generations born there moved away to pursue educational and professional opportunities not available in their hometowns. For example, three of the top eight are prefectures on Shikoku, the only one of Japan’s four main islands without a single Shinkansen station.

Highest percentage of abandoned homes/hochi akiya (compared to total housing units)

● Kagoshima: 13.6 percent

● Kochi: 12.9 percent

● Tokushima: 12.2 percent

● Ehime: 12.2 percent

● Wakayama: 12 percent

● Shimane: 11.4 percent

● Yamaguchi: 11.1 percent

● Akita: 10 percent

Meanwhile, Tokyo has the lowest percentage of abandoned homes, 2.6 percent. Other prefectures with major urban population centers are also low on the hochi akiya ranking, such as Kanagawa (including Yokohama) at 3.2 percent), Aichi (Nagoya) at 4.3 percent, and Osaka, Fukuoka, and Miyagi (Sendai) all at 4.6 percent. Tokyo’s non-Kanagawa neighbors, Saitama and Chiba, also had low abandoned house figures, at 3.9 and 5 percent respectively.

Given these migration patterns, it’s not hard to envision scenarios where someone born in the countryside moves to the big city for school or work and settles down there. Then, when a parent or elderly relative back home passes away, or when the relative themself moves into a newer home now that the kids are grown up and they don’t need as much space, the house sits idle. Maybe the kid who moved away wants to move back to the countryside once they quit the rat race and retire, but that daydream never pans out. Maybe the difficulties of coordinating the sale of an inherited home from halfway across the country means they keep putting the process off until years and years go by, maybe so many that it gets hard to determine who actually legally owns the home anymore. The result? Another abandoned home to add to the total.

With the number of abandoned homes rising, some towns are becoming concerned about potential safety risks such as collapsing during earthquakes, typhoons, or landslides. There isn’t a quick and simple solution to the issue, however. Not only are may abandoned homes in locations where residential demand is low, years of being unoccupied and unmaintained has, according to the report, left an estimated 20 percent of them damaged or decayed to an extent that they’re not for for human habitation without significant restoration work (having recently purchased a hochi akiya of our own here at SoraNews24, we know first-hand how tough that can be), so it’s likely the number of abandoned houses in Japan is going to continue to increase for at least a while.

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Pakutaso

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Tokyo experiences drop in population for seventh consecutive month

Tokyo experiences drop in population for seventh consecutive month The number of elderly people in Japan this year has yet again smashed multiple records

The number of elderly people in Japan this year has yet again smashed multiple records Japan reports fewer children and more elderly people for 35th year in a row

Japan reports fewer children and more elderly people for 35th year in a row The end of the pay phone? Japanese government considering getting rid of phone boxes

The end of the pay phone? Japanese government considering getting rid of phone boxes Japan suffers 37th consecutive year of low birthrate, Japanese people may become extinct someday

Japan suffers 37th consecutive year of low birthrate, Japanese people may become extinct someday Practical Zelda Tears of the Kingdom merch is here to be Hyrule-helpful in your daily life【Pics】

Practical Zelda Tears of the Kingdom merch is here to be Hyrule-helpful in your daily life【Pics】 We check out Otaru’s real-life locales that inspired scenes in hit anime Golden Kamuy

We check out Otaru’s real-life locales that inspired scenes in hit anime Golden Kamuy 2nd line of Casio watch rings hits Japanese capsule machines and we got the secret one!

2nd line of Casio watch rings hits Japanese capsule machines and we got the secret one! McDonald’s Happy Meals in Japan now come with Shinkansen robots

McDonald’s Happy Meals in Japan now come with Shinkansen robots Starbucks releases an official green tea chai latte with special Japanese ingredients

Starbucks releases an official green tea chai latte with special Japanese ingredients Kyoto study finds nearly 500 translation errors for foreign tourists, new guidelines released

Kyoto study finds nearly 500 translation errors for foreign tourists, new guidelines released Japanese public toilet tours become popular with foreign tourists in Tokyo

Japanese public toilet tours become popular with foreign tourists in Tokyo New vending machines at Shinjuku Station emit scent, play projection mapping with your purchase

New vending machines at Shinjuku Station emit scent, play projection mapping with your purchase Mt. Fuji-blocking screen installed as response to bad tourist manners to be in place by next week

Mt. Fuji-blocking screen installed as response to bad tourist manners to be in place by next week Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】 Life-size vibrating Legend of Zelda Master Sword for sale from Nintendo【Photos】

Life-size vibrating Legend of Zelda Master Sword for sale from Nintendo【Photos】 Yes, our new smartphone looks like at least two Studio Ghibli anime characters, Sharp says

Yes, our new smartphone looks like at least two Studio Ghibli anime characters, Sharp says Starbucks releases special matcha Frappuccino made with Japan’s first matcha leaves of the year

Starbucks releases special matcha Frappuccino made with Japan’s first matcha leaves of the year Japanese man tells friend to wear suit to wedding party, so he comes as Mobile Suit Gundam

Japanese man tells friend to wear suit to wedding party, so he comes as Mobile Suit Gundam Studio Ghibli releases new mug and tumbler collection featuring Jiji and Totoro

Studio Ghibli releases new mug and tumbler collection featuring Jiji and Totoro Cool capsule toys recreate how Japan navigated trains in pre-smartphone days【Photos】

Cool capsule toys recreate how Japan navigated trains in pre-smartphone days【Photos】 Fried Pokémon: Tokyo restaurant serves up an unusual dish【Taste Test】

Fried Pokémon: Tokyo restaurant serves up an unusual dish【Taste Test】 McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society New Tokyo restaurant charges higher prices to foreign tourists than Japanese locals

New Tokyo restaurant charges higher prices to foreign tourists than Japanese locals “Mt. Fuji convenience store” issues apology for bad tourist manners, adds multilingual signs

“Mt. Fuji convenience store” issues apology for bad tourist manners, adds multilingual signs Tokyo’s famous Lost in Translation hotel is closed

Tokyo’s famous Lost in Translation hotel is closed Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes Bad tourist manners at Mt Fuji Lawson photo spot prompts Japanese town to block view with screens

Bad tourist manners at Mt Fuji Lawson photo spot prompts Japanese town to block view with screens Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Japan’s Japanese population dropping in every part of the country, foreign population rising

Japan’s Japanese population dropping in every part of the country, foreign population rising Sturgeons in Japanese village outnumber human population, used as marketing strategy

Sturgeons in Japanese village outnumber human population, used as marketing strategy Abandoned Japanese houses transformed into stunning modern homes

Abandoned Japanese houses transformed into stunning modern homes Squat toilets’ popularity fading as parents call for them to be abolished in Japanese schools

Squat toilets’ popularity fading as parents call for them to be abolished in Japanese schools Buying a house in Tokyo? This town is giving away brand new homes to applicants in Japan

Buying a house in Tokyo? This town is giving away brand new homes to applicants in Japan Locked and blocked! Japanese people don’t trust others on social media, survey finds

Locked and blocked! Japanese people don’t trust others on social media, survey finds The price of newly built apartments in central Tokyo skyrocketed over 100 million yen last year

The price of newly built apartments in central Tokyo skyrocketed over 100 million yen last year The Tokyo area welcomed more new foreign residents than Japanese ones last year

The Tokyo area welcomed more new foreign residents than Japanese ones last year Japanese travelers are avoiding Kyoto as the city’s number of foreign visitors continues to grow

Japanese travelers are avoiding Kyoto as the city’s number of foreign visitors continues to grow Japanese schools are losing their pools due to rising maintenance costs and aging facilities

Japanese schools are losing their pools due to rising maintenance costs and aging facilities Are anime and idol songs the musical choice of poor people? Income survey has some otaku worried

Are anime and idol songs the musical choice of poor people? Income survey has some otaku worried Japanese travel agency reveals summer 2022’s most popular destinations domestically and abroad

Japanese travel agency reveals summer 2022’s most popular destinations domestically and abroad Japanese town suffers population decline, turns its local elementary school into an aquarium

Japanese town suffers population decline, turns its local elementary school into an aquarium What will 2021 mean for Valentine’s Day in Japan? Survey asks teens their chocolate plans

What will 2021 mean for Valentine’s Day in Japan? Survey asks teens their chocolate plans What’s the best way to eat Japanese cream stew and rice, “together” or “separate?”【Survey】

What’s the best way to eat Japanese cream stew and rice, “together” or “separate?”【Survey】 Meet the the 90-year-old Japanese woman who is McDonald’s Japan’s oldest female employee

Meet the the 90-year-old Japanese woman who is McDonald’s Japan’s oldest female employee

Leave a Reply