Being able to read is something many people take for granted. I mean, English with its Latin alphabet only consists of 26 letters. Now imagine that the writing system (or script) of your country was changed for political reasons. Cities and towns across the border share almost the same spoken language, but with a totally different way of writing it down. This has been the situation in Mongolia. Drastic changes in scripts throughout the twentieth century have led to recurrent headaches for native readers.

I’ve met many a foreigner in Japan, or third culture kid who despite their fluent spoken language skills was unable to read. Here’s an example. A friend of mine who learned Bulgarian from her parents was visiting her native land. She jumped into a taxi, confident that she’d be driven to her destination, and fluently gave the address. The taxi driver gave her an extremely odd look. It turned out that where she wanted to go was right there, but she couldn’t read the signs to figure that out.

Spoken Japanese is fairly easy to pick up if you live in Japan, while memorizing the bare minimum of 2,136 kanji characters for everyday use requires serious study. And that doesn’t include the incredibly varied characters for personal names or place names. Foreigners who can chat comfortably in Japanese are a lot less likely to be able to read signs or menus, let alone newspapers. Let’s just say I’ve seen even native speakers sneakily looking up how to write a particular kanji on their phones.

Not being able to read easily is tough, wherever you live. In Mongolia, reading can be a huge pain for native speakers… this is why!

– “Ma, why do I have to learn my alphabet twice?”

There are currently two forms of writing the Mongolian language. One is the traditional Mongolian script (“Old Mongol script”) written vertically down the page like this:

The other is Mongolian Cyrillic, written horizontally like this:

Монгол Кирилл үсэг

Cyrillic is used in the state of Mongolia, while the traditional Mongolian script is used in neighboring Inner Mongolia (an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China). You might expect that because Mongolian is now written in Cyrillic it’s similar to Russian, but in terms of grammar Mongolian is much more like Japanese.

Traditional Mongolian script is said to date from 1204, when scribe Tatar-Tonga was captured by the Mongols and introduced the Uyghur form of writing, originally written horizontally. Eventually, this became written vertically—Mongolians might say that happened because it was easier to write down the horse’s neck rather than across.

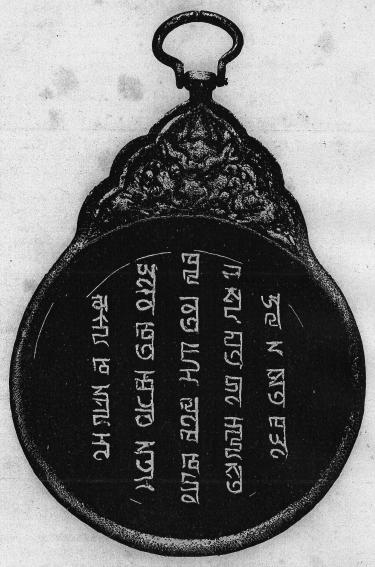

However, by the end of the century this would change. The Yuan dynasty of Kublai Khan (famous grandson of Genghis) promoted the imperial Phagspa script for the vast area they controlled. This intricate writing system was invented by Tibetan lama Zhogoin Qoigyai Pagba for Kublai Khan. It ambitiously aimed to be a script able to be used for all the languages under their sway, including Chinese, Tibetan and Mongolian.

▼ Phagspa script

In 1368 the Yuan dynasty collapsed, and as the Mongols retreated to the steppes, this writing system soon fell out of use and was replaced by traditional Mongolian script once more. The reason Phagspa disappeared so quickly could have been its privileged existence as a faithful representation of the language of the imperial court—it didn’t reflect how ordinary people spoke.

About 600 years later, Mongolian script reached another turning point. In 1921 revolution broke out, and by 1924 communist rule was established in the new Mongolian People’s Republic.

– “Workers of the world, unite!” Different alphabets adopted under Soviet pressure

▼ Latin script propaganda

In 1924, the literacy rate was below 10 percent. Mongolian script was held up to ridicule, and Latin script was named the alphabet of the revolution for writing Mongolian. Away with the old ways of thinking and in with the new—the traditional teaching of Buddhist parables gave way to educational reform.

From the early 1930s, there were attempts to switch from Mongolian to Latin script, but these early attempts met with strong opposition. However, in the latter half of the decade circumstances changed as continued use of Mongolian script was denounced as “nationalist” in the wake of Stalin’s Great Terror. Everyone was forced to support the Latinization of Mongolian writing, in fear for their lives.

In February 1941, the government gave an official green light to the use of Latin script, but the following month, these same public officials decided Mongolian should be written using the same Cyrillic alphabet as Russian. Clearly, there had been some kind of pressure exerted by Moscow.

In the 1950s, linguistically-divided Chinese Inner Mongolia also began to consider adopting Cyrillic. But from the end of the decade the Sino-Soviet split came to a head and cast a pall over this movement, which eventually sputtered and died.

During the perestroika period, Moscow’s grip loosened. People regained their appreciation for tradition, and cultural renaissance was in the air. A new movement to abolish Cyrillic and restore Mongolian script arose. In September 1992, education began in Mongolian script from the first year of primary school. Unfortunately, when these children reached third year, Cyrillic was adopted once more. In the face of harsh economic reality, the budget couldn’t stretch to train teachers and educate students in the vertical Mongolian script.

– Writing systems divided by national borders

As a result, while the state of Mongolia and Chinese Inner Mongolia speak almost the same language, it is written in totally different ways in each country. It’s possible that these writing systems may never be united.

The phenomenon of border lines creating linguistic division can be seen all over the world. A country which gains independence generally wishes to gain independence from the language of the oppressors and a distinct voice, especially if there is a shared border. Crucially, the changes in written Mongolian did not come about through the will of the Mongolian people, but through the political posturing of surrounding nations. Next time you come across a written English word that you don’t know how to pronounce, spare a thought for Mongolia’s differing systems of writing.

Source: Yukiyasu Arai, Japan Business Press

Featured image: Rona Moon

Insert images: Wikipedia, Akihabara Area Blog

Mongolian professor says Japan’s name for Mongolian barbecue, “Genghis Khan,” is disrespectful

Mongolian professor says Japan’s name for Mongolian barbecue, “Genghis Khan,” is disrespectful Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Chinese bootleg invites us to learn about the wonderful world of anime legend…Guzuo Miyazaki?!?

Chinese bootleg invites us to learn about the wonderful world of anime legend…Guzuo Miyazaki?!? Clever font sneaks pronunciation guide for English speakers into Japanese katakana characters

Clever font sneaks pronunciation guide for English speakers into Japanese katakana characters Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of

Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is

Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is Family Mart’s Shibuya Cat Street shop hosts first-ever rescue cat photo exhibition for Cat Day

Family Mart’s Shibuya Cat Street shop hosts first-ever rescue cat photo exhibition for Cat Day Man arrested in Japan after leaving car in coin parking lot for six years, racking up three-million-yen bill

Man arrested in Japan after leaving car in coin parking lot for six years, racking up three-million-yen bill We turn into paranormal investigators, check out the “world’s scariest” haunted spot in the U.K.

We turn into paranormal investigators, check out the “world’s scariest” haunted spot in the U.K. How to turn cold McDonald’s fries into the best hash browns you’ve ever tasted

How to turn cold McDonald’s fries into the best hash browns you’ve ever tasted Second ramen restaurant in Tokyo receives Michelin star for 2017

Second ramen restaurant in Tokyo receives Michelin star for 2017 Site of the worst bear attack in Japanese history is a chilling place to visit

Site of the worst bear attack in Japanese history is a chilling place to visit The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says