Japan’s most famous urban ruins weren’t always deserted, as shown in this video from the 1960s when Gunkanjima’s ghost town was still alive and well.

Looking at the abandoned ruins of Gunkanjima, the island in Nagasaki Prefecture seen in movies such as Skyfall, Battle Royale II, and the live-action Attack on Titan, it can be hard to imagine anyone living there. The structures, deteriorating even as their remains become overgrown with vegetation, have such an atmosphere of oppressive emptiness that it’s easy to forget it really wasn’t all that long ago that Gunkanjima, or Battleship Island, was home to a thriving coal mining community.

▼ Gunkanjima today

It wasn’t until 1974 that the mine was shut down, and while that was the result of a long-coming shift away from coal power in Japan, the facility was still a legitimate enterprise in 1965, when Mainichi News sent a camera crew to record footage of life on Gunkanjima.

The transportation technology of the time made Gunkanjima, officially called Hashima, a one-hour trip from the Nagasaki mainland. Rather than commute by ship, though, the mineworkers lived on the island, along with their families, and in 1965 some 2,700 men, women, and children called Gunkanjima home.

While there were rich mineral deposits to be found below, there was precious little buildable land on the surface of the manmade island. With no direction to build except up, the average apartment house was 10 stories tall, and the Mainichi video reports that “the residents live comfortable lives.”

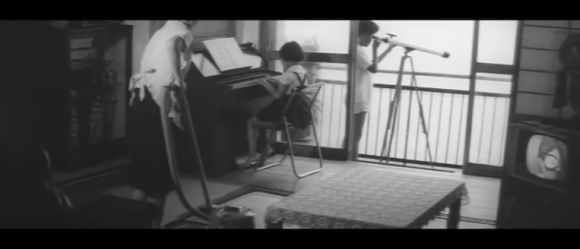

▼ Although with one kid looking through a telescope, the other playing the piano, and Mom vacuuming, we’re not sure why the TV is still on.

Obviously, everyone’s life was in some way linked to the coal mines, from which massive quantities of the ore were pulled up.

Priests were periodically called to the island to pray for the safety of the workers, and even young children would participate in the ceremonies, asking for the protection of their fathers and older, working-age siblings.

After their shift, the miners would come back so covered in soot that they’d hop into the communal tub still wearing their work clothes, turning the water opaque in the process.

The miners weren’t the only ones who spent part of their day underground, though. The island’s topography meant that travelling on the surface from point A to point B meant climbing up and down a series of stairways.

As an alternative, though, there were subterranean passageways that allowed residents to take a more direct course.

Gunkanjima wasn’t exactly brimming with entertainment options, although it reportedly had a movie theater and a pachinko parlor. The video says that fishing was also a popular way for miners to spend their downtime.

There wasn’t any father/son bonding going on there, though. Fishing along the seawall was considered too dangerous for children, so they were prohibited from casting their poles into the ocean. Instead, many took up raising carrier pigeons.

▼ We wonder, did they endlessly bicker over which kind of pigeon was the best, like how gamers argue about Nintendo vs. Sony?

And while the community’s layout meant that there was no advantage to using a bicycle to get around, being able to ride one was still considered a necessary skill for if and when the children left the island, which is why they would practice on the school’s athletic field, one of the few open areas on Gunkanjima at the time.

Another tricky thing to teach kids was an appreciation for nature, seeing as how they were surrounded by concrete high-rises. The 10th-story preschool shown in the video tried to instill some sense of the natural environment with a small indoor garden and fish pond.

▼ A sign near an athletic field with “Let’s all plant grass and trees” written on it

The video closes with the narrator saying, “The people living on the island are hoping to create a warmer atmosphere with more greenery.” Ironically, though, Gunkanjima is now greener than ever after more than 40 years of no one at all living there.

Source: Grape

Images: YouTube/懐かしの毎日ニュース

You can build Japan’s hauntingly beautiful Gunkanjima as a papercraft kit【Photos】

You can build Japan’s hauntingly beautiful Gunkanjima as a papercraft kit【Photos】 Cruising around Gunkanjima, Japan’s otherworldly “Battleship Island”【Photos】

Cruising around Gunkanjima, Japan’s otherworldly “Battleship Island”【Photos】 Check out this absolutely stunning drone video of Nagasaki’s Battleship Island in Ultra HD

Check out this absolutely stunning drone video of Nagasaki’s Battleship Island in Ultra HD Battleship Island: Five Reasons Why More Movie Villains Should Live Here

Battleship Island: Five Reasons Why More Movie Villains Should Live Here Thomas the Tank Engine’s video visit to Japan is more Japanese than life in Japan

Thomas the Tank Engine’s video visit to Japan is more Japanese than life in Japan Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway

Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of

Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is

Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The Sailor Moon theme song is based on another song about drinking a lot of tequila【Video】

The Sailor Moon theme song is based on another song about drinking a lot of tequila【Video】 SoraReview: Mary and the Witch’s Flower, the newest anime from Studio Ghibli director Yonebayashi

SoraReview: Mary and the Witch’s Flower, the newest anime from Studio Ghibli director Yonebayashi Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Anime holy ground – A visit to the real-world location of Look Back【Photos】

Anime holy ground – A visit to the real-world location of Look Back【Photos】 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says