Spokesmen say this week’s ceremony, and another scheduled for October, violate the principal of separation of church and state.

On Tuesday afternoon, the abdication ceremony for Emperor Akihito was held at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. At roughly the same time, though, a different gathering was taking place in the capital’s Shinjuku district, where a number of Japanese Christian organizations, including the Japan Baptist Convention, National Christian Council in Japan, and The Society of Jesus, held a joint press conference to voice their complaint about the ascension ceremony for Akihito’s son, Naruhito, which was scheduled to take place the next day.

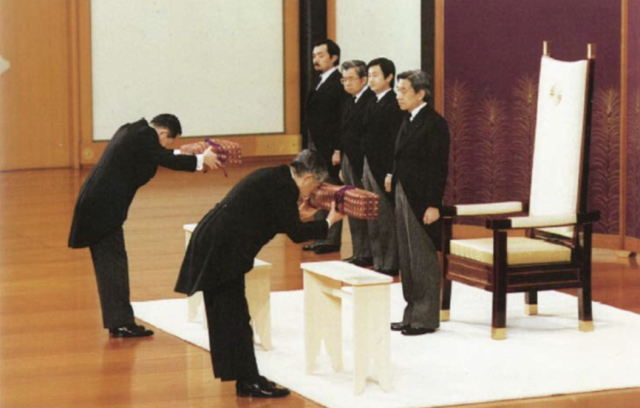

At the heart of the Christian groups’ grievance is the fact that while the imperial changeover is an event of great cultural significance in Japan, there’s a religious aspect to it as well. Traditional Shinto belief holds that Japan’s emperors are the descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu, the religion’s most important deity, and that by extension the emperor himself is a god in human form. In addition, Japan’s imperial regalia, called the Three Sacred Treasures and consisting of a sword, curved bead, and mirror, also have millennia-old connections to Shinto belief, and both the sword and bead are presented to the new emperor during the ascension ceremony.

▼ The sword and bead are presented, within wrappings, to Emperor Akihito during his ascension ceremony in 1989.

This prompted the assembled Christian groups to issue a joint statement declaring the ascension ceremony, an official state function which Prime Minister Shinzo Abe both attended and delivered a speech during, “a violation of the fundamental principles of democratic sovereignty, as well as the separation of government and religion, as specified in the constitution of Japan.” The organizations hold the same opinion about Emperor Naruhito’s enthronement ceremony, the second ceremony in the succession process, which is scheduled to take place in October, saying that the official state status of the ceremonies shows “a resurgence of State Shinto,” a term used to describe the strong reciprocal influences of Shinto doctrines, including the absolute divinity of the emperor, and government policies on each other during Japan’s bellicose political climate during the first half of the 20th century.

However, while Shinto fundamentalists do exist in Japan, it would be an exaggeration to say that the majority of the Japanese people revere the emperor as a god. Naruhito’s grandfather himself, Hirohito, famously made a public statement rejecting the idea that he was a living god following Japan’s surrender in World War II, and in the current era, the emperor is seen more as a symbol of Japan’s traditional values and culture, not as a religious leader.

Since the Emperor of Japan commands no official political power, it’s unlikely that the Japanese Christian groups’ claim that the ascension and enthronement ceremonies constitute a violation of the constitution will lead to any changes in the planned October event, just as Naruhito’s ascension ceremony went on as planned on May 1.

Source: Livedoor News/Asahi Shimbun Digital via Hachima Kiko

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert image: Wikipedia/RSSFSO

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Japanese Christian groups hold press conference to protest emperor’s enthronement ceremony

Japanese Christian groups hold press conference to protest emperor’s enthronement ceremony Buildings used for the emperor’s Daijosai ceremony are open for public viewing until December 8

Buildings used for the emperor’s Daijosai ceremony are open for public viewing until December 8 Japan’s new emperor ascends to throne, makes first speech with wish for peace, happiness

Japan’s new emperor ascends to throne, makes first speech with wish for peace, happiness Heavy rain falls in Tokyo on day emperor is presented with Sword of Heavenly Gathering Clouds

Heavy rain falls in Tokyo on day emperor is presented with Sword of Heavenly Gathering Clouds Pokémon GO player claims his in-game snapshot shows Japan’s new emperor and Pikachu together

Pokémon GO player claims his in-game snapshot shows Japan’s new emperor and Pikachu together Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Which Japanese convenience store has the best plain onigiri rice balls?

Which Japanese convenience store has the best plain onigiri rice balls? Magical senzu beans from Dragon Ball now available in chocolate form!

Magical senzu beans from Dragon Ball now available in chocolate form! 7-Eleven now has make-it-yourself smoothies in Japan, and they’re amazing

7-Eleven now has make-it-yourself smoothies in Japan, and they’re amazing 7-Eleven Japan’s sakura sweets season is underway right now!

7-Eleven Japan’s sakura sweets season is underway right now! Tokyo travel hack: How to enjoy a free sightseeing boat tour around Tokyo Bay

Tokyo travel hack: How to enjoy a free sightseeing boat tour around Tokyo Bay How to make curry in a rice cooker with zero prep work and no water[Recipe]

How to make curry in a rice cooker with zero prep work and no water[Recipe] The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years

Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Donald Trump will probably be the first foreign leader to meet with Japan’s new emperor

Donald Trump will probably be the first foreign leader to meet with Japan’s new emperor Japanese Emperor’s abdication date to be decided next month, expected later than initial reports

Japanese Emperor’s abdication date to be decided next month, expected later than initial reports Emperor of Japan abdicates throne, issues final imperial statement to people of Japan【Video】

Emperor of Japan abdicates throne, issues final imperial statement to people of Japan【Video】 Overworked Japan loses last public holiday of the year, even though it’s still on the calendar

Overworked Japan loses last public holiday of the year, even though it’s still on the calendar Japan issuing beautiful new coins to celebrate Emperor Naruhito’s enthronement

Japan issuing beautiful new coins to celebrate Emperor Naruhito’s enthronement How do you say “Happy New Era” in Japanese?

How do you say “Happy New Era” in Japanese? Poll finds support to let women inherit imperial throne as Japan faces possible succession crisis

Poll finds support to let women inherit imperial throne as Japan faces possible succession crisis Japan announces new era name, Reiwa, but what does it mean and why was it chosen?

Japan announces new era name, Reiwa, but what does it mean and why was it chosen?