In 1963, Kazuo Ishikawa was convicted of the murder of a high school girl in Sayama City, Saitama Prefecture. A member of the Buraku, Japan’s historical untouchable caste, Ishikawa grew up poor and uneducated, and the police built the case against him by taking advantage of his naivety, by capitalizing on social prejudices, and by manipulating an already unfair legal system to their advantage. Now 74, he is still fighting to clear his name and to make sure others have access to a fair trial.

The Case

On May 1, 1963, a female high school student disappeared on her way home from school. That evening, a ransom note was delivered to her home, but soon after a botched attempt to deliver the money allowed a possible culprit to escape, her body turned up in a nearby field, the girl having been raped and murdered. After a team of 40 police investigators failed to make an arrest, public pressure was mounting.

The police decided to investigate a local Buraku area on the off-chance the criminal was there. The burakumin as they are sometimes called in Japanese are not an ethnic minority, but a social one. In the feudal era, people who were cast out from society or engaged in professions considered unclean, like undertakers or tanners, lived in separate villages or ghettos. Even in modern times, they are negatively stereotyped as especially criminal and lazy.

The police picked up Ishikawa on an unrelated charge, as well as a few other youths from the Buraku district. Ishikawa was released on bail, but then they decided to go after him for the murder and took him into custody again.

The Substitute Prison System and Forced Confessions

Ishikawa was held in police detention for a total of 47 days, with access to his lawyer limited to five minutes at a time and subjected to 16-17 hour interrogation sessions.

This treatment is actually permissible under Japanese law. Detainees can be held under the direct police management for up to 23 days before formal charges are laid. After a warrant is issued, the police can hold a person for 72 hours without laying charges. If they deem that is not sufficient, they can apply for two 10-day extensions. However, if the person faces multiple charges, the charges can be dealt with separately and the process repeated over and over.

Keeping a suspect in direct custody makes things much easier on the police. In comparison with the rules governing a state detention center run by the Ministry of Justice, in police detention lawyers cannot be present in an interrogation, nor can it be videotaped or tape-recorded. There is no legal limit on the length of the interrogation sessions, nor is there a law stipulating that matters raised during interrogation have to be related to the charges. The ‘confessions’ are not actually written or dictated by the detainee but composed by the police and simply signed by the detainee.

During this time, the suspect is not legally guaranteed access to a lawyer, except in cases involving the death penalty–a provision that wouldn’t have helped Ishikawa anyway, as it was enacted in 2006.

While he was in custody, the police intimidated Ishikawa, threatening to arrest and prosecute his brother, the sole breadwinner in the family at that time, if he did not confess to the crime. They also misleadingly assured him that if he did confess, he could plea out to 10 years instead of getting the death penalty. Eventually, broken down by the long interrogations sessions and thinking he was protecting his family, Ishikawa agreed to confess.

“Things didn’t turn out the way the police had told me,” Ishikawa says. “I was sentenced to death, and my brother lost his job anyway, because people refused to employ someone related to a confessed murderer. My younger sister was harassed out of school. Those years in prison were really tough for me.”

Appeal After Appeal

Ishikawa was sentenced to death on March 11, 1964. On appeal at the Tokyo High Court in 1974, they confirmed his guilty verdict on the weight of his confession, although he had retracted it. They did, however, reduce his sentence to life. That case then made it to the Supreme Court, but no effort was made to investigate how Ishikawa’s confession was obtained or to look into unreleased evidence, and they upheld the verdict again.

In fact, there may have been exonerating evidence all along. Japanese law only requires that evidence used in court by the prosecution be disclosed to the defense. All other evidence can be withheld.

In Ishikawa’s case, a large amount of evidence remains undisclosed, as evidenced by missing sequential numbers in the evidence list. The defense has stated that they are willing to have any sensitive data in the documents blacked-out to protect the privacy of concerned parties and that they would be willing to examine this evidence only in the prosecutor’s office, but the prosecution continues to deny them access or even release a list of the types of evidence they hold.

A Prison Education

Ishikawa would eventually serve 32 years of hard labor in prison, but he says the time was not completely wasted. In prison, a guard taught him how to read and write, and this opened up a whole new world for him.

“My parents never told us anything about Buraku issues. I don’t even know if they ever even mentioned the word. They had to have known it, had to have some idea that they were from a Buraku, but they never told us anything about it,” he says.

“It was only after those years of study in jail that I learned that the things I had experienced as a child were something happening all over Japan. I learned that I was from a Buraku and that’s why my family faced such poverty and that’s why I went to jail for a crime I didn’t commit.”

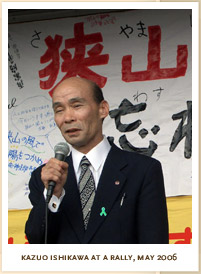

Parole, but Not Freedom

In 1994, Ishikawa was released on parole, but still continues to suffer the stigma of a murder conviction as well as the restrictions of a parolee. He continues to make public appearances to talk about the case and to advocate for judicial reform and minority rights. Over 1 million people have signed a petition asking the government to retry his case.

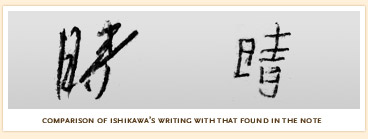

In 2006, he and his defense team launched a third appeal for retrial. Focusing on exculpatory evidence such as the lack of any similarity between the handwriting on the ransom note and Ishikawa’s handwriting and the the fact that his fingerprints do not appear anywhere on it or the envelope, the team hopes that this final appeal will be successful.

“I am actually not asking the court to quickly give me a not-guilty verdict because I am innocent. I am only asking that the court review the evidence, and the truth will reveal itself in the process,” he said at the time.

Yet, it is now the 50th anniversary of the crime and nearly seven years after this most recent request for an appeal, but the court has not yet issued a decision. For Ishikawa, time is running out, but he says he will keep fighting.

“My time in prison was difficult, but… I connected with a movement that extends beyond me and affects the lives of thousands of people all over Japan. It is for these people as much as for myself that I fight for recognition of my innocence.”

Photos: RocketNews24, Buraku Liberation and Human Rights Research Institute, IMADR

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag

Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results

Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Sanrio brings some smiles to Evangelion with new collaboration merch line【Photos】

Sanrio brings some smiles to Evangelion with new collaboration merch line【Photos】 Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag

Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results

Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Sanrio brings some smiles to Evangelion with new collaboration merch line【Photos】

Sanrio brings some smiles to Evangelion with new collaboration merch line【Photos】 The fish in rural Fukui that rivals Japan’s most auspicious sea bream

The fish in rural Fukui that rivals Japan’s most auspicious sea bream Final Fantasy and Shinkansen announce collaboration with in-train audio play, SD art and merch

Final Fantasy and Shinkansen announce collaboration with in-train audio play, SD art and merch Convenience store onigiri rice balls become even more expensive…but are they worth it?

Convenience store onigiri rice balls become even more expensive…but are they worth it? Michelin-approved Japanese chef teaches us two gourmet-standard dishes using ice cream and toast

Michelin-approved Japanese chef teaches us two gourmet-standard dishes using ice cream and toast Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says The fish in rural Fukui that rivals Japan’s most auspicious sea bream

The fish in rural Fukui that rivals Japan’s most auspicious sea bream Final Fantasy and Shinkansen announce collaboration with in-train audio play, SD art and merch

Final Fantasy and Shinkansen announce collaboration with in-train audio play, SD art and merch Convenience store onigiri rice balls become even more expensive…but are they worth it?

Convenience store onigiri rice balls become even more expensive…but are they worth it? Michelin-approved Japanese chef teaches us two gourmet-standard dishes using ice cream and toast

Michelin-approved Japanese chef teaches us two gourmet-standard dishes using ice cream and toast Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Playing Switch 2 games with just one hand is possible thanks to Japanese peripheral maker

Playing Switch 2 games with just one hand is possible thanks to Japanese peripheral maker Bizarre or brilliant? Takoyaki and okonomiyaki rice balls available in convenience stores now

Bizarre or brilliant? Takoyaki and okonomiyaki rice balls available in convenience stores now The 10 best Japanese hot spring resorts locals want to go back to again and again

The 10 best Japanese hot spring resorts locals want to go back to again and again Abuse Cafe Japan: We get abused by waitresses in maids’ uniforms at Tokyo’s viral pop-up diner

Abuse Cafe Japan: We get abused by waitresses in maids’ uniforms at Tokyo’s viral pop-up diner Passing the JLPT N1 — Here’s how I did it, so you can too!

Passing the JLPT N1 — Here’s how I did it, so you can too! New sake earrings let you wear your love for Japanese rice wine on your ears

New sake earrings let you wear your love for Japanese rice wine on your ears Nearly one in ten young adults living in Japan isn’t ethnically Japanese, statistics show

Nearly one in ten young adults living in Japan isn’t ethnically Japanese, statistics show Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now

Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026