Like so many foreigners living in Japan, I first entered the country as an eigo shidou joshu, more commonly known as an Assistant Language Teacher, or ALT for short. Although terms like “grass-roots internationalisation” and “globalisation” are uttered during ALT training seminars and by boards of education across the country with such frequency that you’d swear they’re being sponsored to use them, in reality an ALT’s role at a Japanese junior high school (where the majority in Japan are employed) is to go along to class with a non-native Japanese teacher of English (or JTE) and, as their job title implies, assist in teaching. The idea is that students, particularly those from rural areas, will benefit from the presence of and instruction from a native English speaker.

But are native speakers entirely vital to English language education in Japan? And should native English speakers, rather than Japanese teachers of English, be the ones taking the lead role in the classroom?

Readers of Japan Today, one of RocketNews24’s own partners, recently took to their keyboards to discuss the role of ALTs in Japan’s schools and whether English ought to be taught by native speakers. Occasionally controversial Japanese culture blogger Madame Riri later analysed these responses and revealed to the Japanese-speaking online community that “ALTs feel that native speakers are not necessarily required in Japanese schools, but much of the problem [with English education in Japan] lies with the English language ability of Japanese teachers of English.”

Through my own five years’ experience in the role and having heard, read, and even actively collated accounts from others who have taught in Japan, I can honestly say that the amount an ALT actually “assists” in a typical English class in Japan depends on a number of factors, from the attitude and English language ability of the JTE whose class they are joining to the skills an individual ALT possesses and the amount of time they have at each school. Particularly in the Japanese government-sponsored JET Programme, the phrase “every situation is different” was something of a mantra during my time as an ALT, and for good reason, though perhaps not the one it was originally intended: while some ALTs are never off their feet and find their job infinitely rewarding, others spend a vast amount of their day sitting at their desks with nothing to do and, feeling completely redundant, can’t wait to leave at the end of the day.

But surely with all that taxpayer money going into schemes like the JET Programme, there must be some benefit to having a native speaker present in English classes? And for that matter, wouldn’t it be better if the main (Japanese) English teachers themselves were native speakers?

Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting comments from Japan Today’s readers on the subject, and how they feel native speakers could be better utilised at schools in Japan.

- Leave pronunciation to the native speaker, please

“There are times when a non-native teacher simply doesn’t know if their students are pronouncing a word correctly,” wrote one commenter. “I once even taught some of my students perfect native pronunciation for an interview they were taking, but the Japanese interviewer couldn’t understand what they were saying. You’ve got to be kidding me!”

Providing native speakers to give pronunciation guidance sounds like such an obvious point to make, but I’m afraid to say that during my years as an ALT there were times when some, shall we say less enthusiastic, teachers I worked with would actually tackle the pronunciation of new words themselves, leaving me standing to the side like a lemon. During my first week on the job, one teacher actually had her entire class repeat the word “maneh” (money) after her while I looked on in abject horror, immediately wanting to teach the kids the correct way to say it but well aware that pointing the teacher’s mistake in front of her 33 students might not be the best move. (I resolved to move on to the next subject as quickly as possible and quietly told the teacher at the end of the class, in case you were wondering.)

But is correct pronunciation really all that important in the Japanese educational system?

- Test scores are king

Perhaps the most frustrating thing for ALTs, and dare I say it JTEs who are passionate about English and would love their students to achieve true fluency, is that English education in Japan is almost entirely focused on test scores, with speaking and listening being given something of a back seat for the most-part.

“English language education in Japanese schools is all focused on the paper test;” wrote one commenter, “If you want to focus on a test of vocabulary and grammar then it doesn’t matter if the teacher is a native English speaker or not.”

For all the love and passion ALTs and (some) JTEs may have for the language, what matters as far as schools, universities, PTAs, Boards of Education and even parents are concerned are the scores students get on their end-of-year and entry tests. The majority of English tests are designed to test students’ understanding of grammar and the size of their vocabulary alone, and so with the right amount of focused study it’s possible for a student to ace a test without having to open their mouth even once.

- Hire communicators, not grammarians

“Japanese teachers place far too much emphasis on English grammar,” wrote another commenter, alluding to the amount of time some teachers spend breaking down English sentences and providing students with lists of verbs and how they are conjugated. And having been quizzed with numerous grammar-related questions myself, I can’t help but agree.

Had it not been for my prior training, I can honestly say that I would have been at a total loss when some of my Japanese colleagues approached me with questions about the past participle and verbs in the perfect tense during my five years as an ALT. Terms that even native speakers have no business knowing are discussed with great frequency in English classes in Japan, and many teachers have their kids recite lists of verbs in every form and have them use differently coloured ink for verbs, adjectives, nouns and adverbs in their writing. Perhaps part of the reason some ALTs become a third wheel in class is because some JTEs, whether out of choice or necessity, devote such time and energy to grammatical analysis of the English they are teaching.

“Japanese schools should be hiring JTEs who have had experience of living overseas, or native speakers who majored in Communications,” the same commenter suggests as a means of breaking out of this grammar-focused approach. “There are so many teachers at schools in Japan who simply cannot speak English.” Perhaps she’s got a point – after all, what is language besides a way to communicate?

- One doesn’t have to be “native” to teach English

“So long as they are well educated and receive proper training, the nationality of an English teacher really doesn’t matter,” said one commenter. “English teaching isn’t limited to just native speakers.” Another wrote: “There are tons of people from countries like Africa and India who speak two or three languages, and whose English ability is on par with a native speaker. I taught English at a Japanese high school, and the Japanese teacher I worked with had, due to her husband’s job, spent time abroad. She spoke incredibly well, and was able to provide explanations in both Japanese and English.”

Indeed, it would be wrong to suggest that a teacher who is not, technically speaking, a “native” English speaker cannot possess native-level English ability, and JTEs with a natural gift for the language should not be seen as inferior to their foreign, English-speaking colleagues. But are there enough Japanese teachers of English whose English ability could be relied upon in this way? Our next commenter thinks not.

- Japanese teachers are bad at English

“I think that the ideal way to teach English is to have a Japanese teacher of English and a native English speaker working together. But the problem is that there are many JTEs whose English level is low to the point that it is not possible to actually communicate properly. This is especially common in junior high and high schools in Japan.”

No doubt due to the profound emphasis that is placed on the ability to read well and understand English grammar rather than speaking and putting the language to use, it is startling just how low some (far from all–there are some superb English speakers amongst teachers in Japan) teachers’ English speaking ability can be. It’s easy to laugh when you hear examples of JTEs whose colleagues jokingly leave pamphlets for English conversation schools on their desk, or of English teachers who reply to a simple “Hello, Mr. XX. How are you?” with “I’m fine too!” (true story), but it does not bode well for future generations of English speakers in Japan when many of those educating them today genuinely struggle to communicate their wishes and teaching plans to ALTs, or indeed respond to a simple greeting in the hallway.

Teachers don’t all have to be the Yodas of their field of education, but equally no one wants to learn lightsabre duelling from a young Luke Skywalker, even if he knows exactly how to disassemble, clean, and re-wire his lightsabre.

- The solution?

As Madame Riri suggests, the general consensus between ALTs in Japan seems to be that native English speakers, be they assistants or the main English teacher, are a valuable asset to schools – if used properly. Ultimately, it’s called “team teaching” for a reason, and as this final commenter suggests, it’s down to teachers to make the most of the skills they have and to work well as a pair. “For listening and speaking, it’s got to be a native speaker. For reading and writing, it’s probably better to have someone who can provide explanations in ones mother tongue.”

What do you think of English education in Japan? Have you ever worked as an ALT? If so, how do you think the presence of a native speaker – given that so little emphasis is given to speaking – is beneficial to students? If you could make any changes to the way English is taught in Japan, what would you do? Let rip in the comments section below!

Source: Madame Riri

Top image: Gap Year

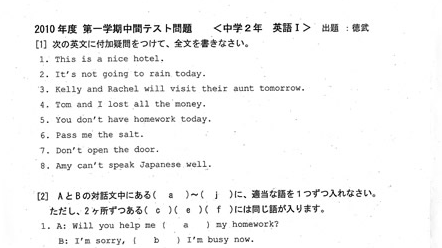

Inset image: Hitotsubashi Chukouikkan,

What’s wrong with English education in Japan? Pull up a chair…

What’s wrong with English education in Japan? Pull up a chair… Want to live and work in Japan? Apply to the JET Program this fall!【Video】

Want to live and work in Japan? Apply to the JET Program this fall!【Video】 English teachers in Japan apologize for having low-proficiency kids say “poison” in assigned video

English teachers in Japan apologize for having low-proficiency kids say “poison” in assigned video Japan reaches its lowest-ever ranking on Education First’s 2024 English Proficiency Index

Japan reaches its lowest-ever ranking on Education First’s 2024 English Proficiency Index ALT in Japan asked to remove earrings by Board of Education

ALT in Japan asked to remove earrings by Board of Education Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now

Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Sync! Illumination lets you watch Tokyo Disneyland Electrical Parade from home on multiple phones

Sync! Illumination lets you watch Tokyo Disneyland Electrical Parade from home on multiple phones 566 million yen in gold bars donated to Japanese city’s water bureau

566 million yen in gold bars donated to Japanese city’s water bureau Japanese video 18-Year-Old Grandpa has important, moving message behind its silly-sounding title

Japanese video 18-Year-Old Grandpa has important, moving message behind its silly-sounding title Photos from 140 years ago show Tokyo’s skyline was amazing long before the Skytree was ever built

Photos from 140 years ago show Tokyo’s skyline was amazing long before the Skytree was ever built Shin Godzilla trailer released, hits very close to home【Video】

Shin Godzilla trailer released, hits very close to home【Video】 Top 100 manga of all time chosen by survey of 150,000 Japanese people

Top 100 manga of all time chosen by survey of 150,000 Japanese people Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results

Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says The anime girl English teacher textbook character that stole Japan’s heart has gotten a promotion

The anime girl English teacher textbook character that stole Japan’s heart has gotten a promotion Japanese student’s “drug dealer” English gaffe confuses foreign ALT

Japanese student’s “drug dealer” English gaffe confuses foreign ALT The reason why Japanese students don’t pronounce English properly

The reason why Japanese students don’t pronounce English properly Under 35 percent of middle school English teachers in Japan meet government proficiency benchmark

Under 35 percent of middle school English teachers in Japan meet government proficiency benchmark Over half of Japanese students in nationwide test score zero percent in English speaking section

Over half of Japanese students in nationwide test score zero percent in English speaking section Is Japan overworking its teachers? One exhausted educator says, “YES!”

Is Japan overworking its teachers? One exhausted educator says, “YES!” Kyoto Board of Education administers English test for teachers with disheartening results

Kyoto Board of Education administers English test for teachers with disheartening results American English teacher fired from Japanese high school after exposing genitals

American English teacher fired from Japanese high school after exposing genitals English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect

English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect Foreign English teacher in Japan calls student’s ability garbage, says it was an “American joke”

Foreign English teacher in Japan calls student’s ability garbage, says it was an “American joke” When “yes” means “no” — The Japanese language quirk that trips English speakers up

When “yes” means “no” — The Japanese language quirk that trips English speakers up American English teacher in Japan takes a moment to remind student that anime is not real

American English teacher in Japan takes a moment to remind student that anime is not real Foreign English teacher in Japan caught hitting 2-year-old child at daycare facility 【Video】

Foreign English teacher in Japan caught hitting 2-year-old child at daycare facility 【Video】 Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker

Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker 20 percent of Japanese junior high students score a zero on nationwide English writing test

20 percent of Japanese junior high students score a zero on nationwide English writing test