With the 26 letters of the alphabet, we can make pretty much any sound present in the majority of languages. But Japanese just doesn’t contain certain sounds present in English, like “th” or “v”, and their “r” is somewhere right between our “r” and “l”, making them sound almost exactly the same to Japanese ears.

Since most Japanese people grow up only speaking Japanese, it means that when they start learning English at school, they either have to learn entirely new sounds (difficult) or else try to render English in Japanese sounds (which isn’t accurate). As a result, many Japanese English learners feel a lot of anxiety over the accuracy of their pronunciation. But should that really be holding them back?

Japanese syllables generally consist of the vowels a, i, u, e, o, and consonant-vowel compounds such as ka, shi, tsu, etc. Therefore, rendering English into Japanese pronunciation results in extraneous sounds. Take, for example, the anime buzzword “waifu“, from the English word “wife”. In Japanese, this can only be rendered into three syllables: WA, I, and FU. The extra “u” sound at the end sounds odd to native English-speaking ears, but is perfectly natural in Japanese. In fact, our cut-off consonants probably sound pretty weird to them, like we’re only pronouncing half of the letter.

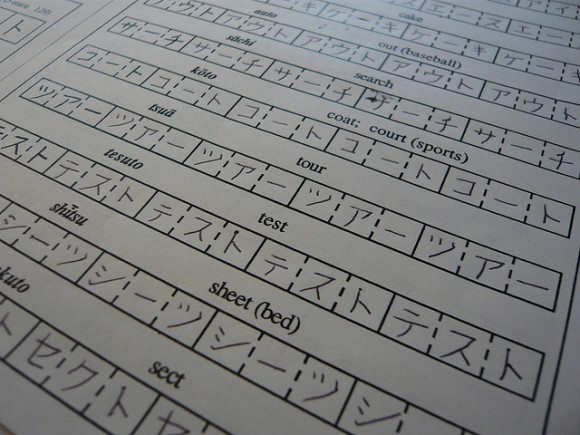

Rather than learning English the way a native-speaking child would, through memorising phonics, many Japanese students rely on pronunciation guides which provide that word in a Japanese pronunciation. Known as “Katakana English”, rendering English into Japanese script actually impedes learning, and is an almost impossible habit to break. Sometimes, however, it’s just too difficult for an ear untrained to English to discern a word without the “crutch” of a Japanese pronunciation. Just the other day, I was talking to a Japanese friend about RocketNews24, and I lazily pronounced it “Rocket News”. After a puzzled silence, I tried “Roketto Nyuusu” and was finally met with a smile of recognition.

As we’ve previously lamented, much of the English education in Japanese schools revolves around standardised test-taking and memorising written grammar over learning pronunciation. So it’s probably not much of a surprise that Japanese people who learn English as a second language tend to have a Japanese accent to some degree. But is this really a Japan-specific thing? Personally, I’ve known many people from a variety of countries who speak excellent English as their second language, yet still retain a distinctive accent. It doesn’t mean that their English is any less accurate.

So why is it that Japanese people are so paranoid about their accent?

▼ Recently, English education in Japan is increasingly leaning towards emphasising spoken English.

Paradoxically, Japanese English learners can sometimes feel more comfortable speaking English with other English speakers rather than in front of their fellow Japanese. The other day I went to a nail salon in Tokyo, and was assigned a nail technician who had recently returned from a working holiday in the US. She was so nervous about the prospect of speaking English to me in front of her Japanese colleagues she was practically trembling, but once the novelty wore off and the others stopped paying attention, she relaxed. “I don’t mind speaking English with English-speaking people,” she explained, “But I can’t do it in front of other Japanese people.”

Recently, a TV interview in English with New York Yankees’ pitcher Masahiro Tanaka caught the attention of Japanese netizens because they didn’t feel his English was accurate enough. “He said ‘My name is’;” complained one Japanese commenter, “nobody actually says that in English, it sounds old-fashioned!” Others, thankfully, were quick to respond with comments along the lines of “Who cares? It’s still English!” and another commenter stated: “Now I know why Japanese people are so scared to be seen speaking English in front of other Japanese people. It seems native English speakers are more understanding! What’s that about?”

▼ Masahiro Tanaka. Skilled pitcher, budding bilingual.

It may be too late now for many Japanese English speakers to go back and undo years of standardised tests and “Katakana English” lessons, but it seems that the more immediate issue is overcoming that pronunciation anxiety and just relaxing into it. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with being a perfectionist, but it’s important not to sweat the small stuff. And as far as problems rank, having a bit of an accent when you speak really isn’t such a big deal after all, is it?

Source: Togetter, Japan Times, Naver Matome

Main Image: Flickr © Jessica Spengler

Inset Images: Flickr © Official US Navy, Flickr © Arturo Pardavila III

Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker

Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker Chopstick anxiety: Painfully shy Japanese diners struggle with communal restaurant containers

Chopstick anxiety: Painfully shy Japanese diners struggle with communal restaurant containers The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu”

The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu” RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese

RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese The top 10 hardest Japanese words to pronounce – which ones trip you up?【Video】

The top 10 hardest Japanese words to pronounce – which ones trip you up?【Video】 Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience

Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan

How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir

New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration

Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】

High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】 Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide

Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide New Nintendo Lego kit is a beautiful piece of moving pixel art of Mario and Yoshi【Photos】

New Nintendo Lego kit is a beautiful piece of moving pixel art of Mario and Yoshi【Photos】 Japan’s cooling body wipe sheets want to help you beat the heat, but which work and which don’t?

Japan’s cooling body wipe sheets want to help you beat the heat, but which work and which don’t? Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys

Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys “The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】

“The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】 Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan

Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters

Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches

McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous?

Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous? Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not

Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists

Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners

To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners 10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan

10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear

Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka

Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model

Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose

Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】

Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】 Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan What’s wrong with English education in Japan? Pull up a chair…

What’s wrong with English education in Japan? Pull up a chair… Japanese expat remembers the words that changed his life when he started working in Australia

Japanese expat remembers the words that changed his life when he started working in Australia “We wasted so much time in English class” — Japanese Twitter user points out major teaching flaw

“We wasted so much time in English class” — Japanese Twitter user points out major teaching flaw Westerners in Japan – do they really ALL speak English? 【Video】

Westerners in Japan – do they really ALL speak English? 【Video】 Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them

Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them Blind Filipino girl Elsie stuns with her mature singing voice【Videos】

Blind Filipino girl Elsie stuns with her mature singing voice【Videos】 Over half of Japanese students in nationwide test score zero percent in English speaking section

Over half of Japanese students in nationwide test score zero percent in English speaking section Everyday Japanese names that make English speakers chuckle

Everyday Japanese names that make English speakers chuckle When “yes” means “no” — The Japanese language quirk that trips English speakers up

When “yes” means “no” — The Japanese language quirk that trips English speakers up “Same sh*t different day” – Nice Japanese people swearing in English 【Video】

“Same sh*t different day” – Nice Japanese people swearing in English 【Video】 Foreign English teacher in Japan calls student’s ability garbage, says it was an “American joke”

Foreign English teacher in Japan calls student’s ability garbage, says it was an “American joke” English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect

English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect Nihon-no: Is an entirely English-speaking village coming to Tokyo?

Nihon-no: Is an entirely English-speaking village coming to Tokyo? Japanese anime girl virtual YouTuber also speaks perfect English!【Video】

Japanese anime girl virtual YouTuber also speaks perfect English!【Video】 Keisuke Honda apologises for English mistake at press conference 【Video】

Keisuke Honda apologises for English mistake at press conference 【Video】 Under 35 percent of middle school English teachers in Japan meet government proficiency benchmark

Under 35 percent of middle school English teachers in Japan meet government proficiency benchmark Top 10 most irritating Japanese borrowed words – Part 2 (The people’s top 10)

Top 10 most irritating Japanese borrowed words – Part 2 (The people’s top 10)

Leave a Reply