Producer of When Marnie Was There pontificates on psychological differences between men and women.

You’ll find very few entities in any creative field that enjoy the sort of widespread respect and goodwill that Studio Ghibli does. The studio’s animated films are consistently held up as shining examples of theatrical storytelling, a feat that’s all the more impressive when you consider how passionate and opinionated anime fans can be.

As such, many fans of animation, both Japanese and in general, were looking forward to the June 10 U.K. release of Ghibli’s latest, and possibly last, film: When Marnie Was There. Despite premiering in Japan in July of 2014 and making its way to the U.S. in 2015, it’s taken two years for the film to arrive in U.K. theaters, despite being an adaptation of the novel of the same name by British author Joan G. Robinson.

And yet, a comment from Yoshiaki Nishimura, one of the film’s two co-producers, has some Ghibli fans who’d been no doubt excited to see Marnie seeing red instead.

Along with Marnie director Hiromasa Yonebayashi, Nishimura recently traveled to London to promote the film’s U.K. opening. While there, the pair sat down with The Guardian correspondent Chris Michael. While the majority of the interview, which can be found here, deals with the themes in Marnie and their connection to Japanese culture and society, at one point Michael asks “Will Ghibli ever employ a female director?” to which Nishimura responds:

“It depends on what kind of a film it would be. Unlike live action, with animation we have to simplify the real world. Women tend to be more realistic and manage day-to-day lives very well. Men on the other hand tend to be more idealistic – and fantasy films need that idealistic approach. I don’t think it’s a coincidence men are picked.”

It didn’t take long for the 38-year-old Nishimura’s logic to elicit a negative response on the English-speaking Internet.

https://twitter.com/sewzinski/status/739879220403273728was looking forward to rewatching Princess Mononoke next week but reading stuff like this is sort of a mega downer https://t.co/ngxke9T2zh

— Fergal (@Fergtron) June 8, 2016

Oooh... I used to be a huge fan till I heard I'm unable to imagine and fantasise coz I'm a girl. GFYS https://t.co/5HpLD0JXFP

— Olivia Quinn 🇺🇦 (@_olivia_quinn) June 7, 2016

Nishimura’s remarks are surprising for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that the vast majority of Ghibli’s films have a female protagonist. In addition, the studio’s Kiki’s Delivery Service, Only Yesterday, Whisper of the Heart, Howl’s Moving Castle, Tales from Earthsea, Arrietty, When Marnie Was There, and Ocean Waves are all based on novels or manga written by women. Of Ghibli’s true adaptations, only Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbors the Yamadas come from source material with a man as their sole creator (the manga version of From Up on Poppy Hill was written by a man and illustrated by a woman).

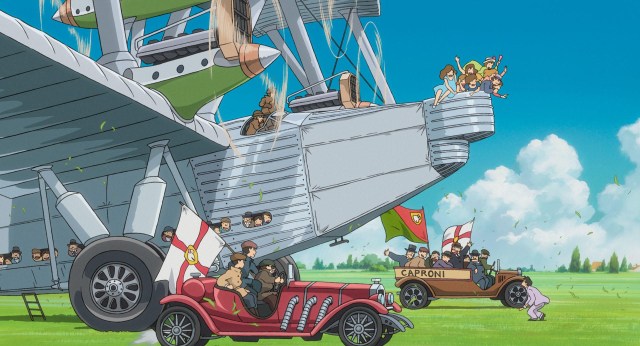

▼ While The Wind Rises takes elements from an identically titled book by a male author, the Ghibli movie is largely Miyazaki’s own story.

Still, Nishimura wasn’t expressing skepticism at women’s ability to write or draw fantasy, only to direct it in animated form. Again, that’s a pretty broad-brushed, and far-less-than-sensitive, generalization, although he doesn’t frame his statement as pointing out a shortcoming per se, but rather a difference in natural tendencies between the sexes he claims to have observed.

On the other hand, a comment by Yonebayashi in the same interview suggests that rather than a discrepancy in how male and female directors approach storytelling across the board, he feels they might react differently depending on the gender of the characters their project is centered on.

“I’m male myself, and if I had a central character who was male, I’d probably put too much emotion into it, and that would lead to difficulty in telling the story.”

While Nishimura’s remarks are hardly diplomatic, they could stem from Ghibli’s oddly insular position in the anime industry. Unlike other studios which are primarily staffed on a rotating, per-project basis, Ghibli retains its workers as regular employees. While that policy creates stability, it also makes the studio somewhat removed from outside trends such as the increased role of, and demand for, female-helmed works of fiction.

Finally, while Nishimura’s statement is being interpreted by many as “Ghibli won’t hire female directors,” it’s worth considering that, in general, Ghibli doesn’t hire directors who aren’t Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata. Of Ghibli’s 21 features (including the made-for-TV and often forgotten Ocean Waves), studio co-founders Miyazaki and Takahata directed 13, including the first seven. It wasn’t until nine years after Castle in the Sky Laputa, the first release under the Ghibli name, that someone other than them, Yoshifumi Kondo, sat in the director’s chair for Whisper of the Heart, and even that was with Miyazaki writing the script.

After that came Princess Mononoke (directed by Miyazaki), My Neighbors the Yamadas (directed by Takahata), and Spirited Away (Miyazaki again). 2002’s The Cat Returns was the first Ghibli theatrical release without Miyazaki or Takahata handling direction or scriptwriting, and you have to go all the way to From Up on Poppy Hill in 2011, directed by Hayao’s son Goro, for the first time someone other than Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata directed a Ghibli movie for the second time (and once again, Goro’s father was involved in writing the script).

As a matter of fact, when you look at the history of Studio Ghibli, there are only four features (again, including Ocean Waves) that don’t have the elder Miyazaki or Takahata as a director, writer, or producer, which suggests the atmosphere at Ghibli might be less “old boys’ club” and more “club for two old boys.” Also, female writers Keiko Niwa and Riko Sakaguchi collectively have co-writing credits for four of Ghibli’s last five scripts.

Nevertheless, with Ghibli currently appearing more than a little rudderless in the post-Miyazaki era, it might want to take a closer look at female directors to help the studio find its direction.

Source: The Guardian via Hachima Kiko

Top image: Studio Ghibli

Insert images: Studio Ghibli (1, 2, 3)

Hayao Miyazaki spends retirement from anime by…spending every day at his animation studio

Hayao Miyazaki spends retirement from anime by…spending every day at his animation studio Poster for Ghibli’s new movie under fire … from the big guru himself!

Poster for Ghibli’s new movie under fire … from the big guru himself! New anime from director of When Marnie Was There is a Ghibli movie in everything but name【Video】

New anime from director of When Marnie Was There is a Ghibli movie in everything but name【Video】 Our take on Studio Ghibli’s newest anime, When Marnie Was There【Impressions】

Our take on Studio Ghibli’s newest anime, When Marnie Was There【Impressions】 Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki retires as producer

Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki retires as producer Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels

Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag

Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag We try five menu recommendations from a clerk at CoCo Ichibanya and almost fall in love

We try five menu recommendations from a clerk at CoCo Ichibanya and almost fall in love Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now

Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now Kura Sushi adding premium tier pricing for better chance at capsule machine game

Kura Sushi adding premium tier pricing for better chance at capsule machine game Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Tokyo Station staff share their top 10 favorite ekiben

Tokyo Station staff share their top 10 favorite ekiben Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Former Ghibli Producer Apologizes: ‘Gender Has Nothing to Do With Making Movies’

Former Ghibli Producer Apologizes: ‘Gender Has Nothing to Do With Making Movies’ American singer to perform theme song for newest Studio Ghibli film 【Video】

American singer to perform theme song for newest Studio Ghibli film 【Video】 Hayao Miyazaki turns down offer to watch new anime film from former Studio Ghibli director

Hayao Miyazaki turns down offer to watch new anime film from former Studio Ghibli director Anime critic thinks Miyazaki may be unable to fill Ghibli talent void quickly enough for new film

Anime critic thinks Miyazaki may be unable to fill Ghibli talent void quickly enough for new film Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There nominated for Academy Award

Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There nominated for Academy Award Ghibli successor Studio Ponoc announces new theatrical anime for release this summer【Video】

Ghibli successor Studio Ponoc announces new theatrical anime for release this summer【Video】 Ghibli casts its 1st film with 2 female leads & all-English theme song

Ghibli casts its 1st film with 2 female leads & all-English theme song Studio Ghibli’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya nominated for Academy Award

Studio Ghibli’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya nominated for Academy Award Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There previewed 30 seconds in aired footage

Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There previewed 30 seconds in aired footage Ghibli’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya gets a North American release date and new trailer 【Video】

Ghibli’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya gets a North American release date and new trailer 【Video】 Former Ghibli producer has (somewhat) harsh words about the Ghibli working environment

Former Ghibli producer has (somewhat) harsh words about the Ghibli working environment New anime movie from former Studio Ghibli members is adaptation of British children’s book【Video】

New anime movie from former Studio Ghibli members is adaptation of British children’s book【Video】 Studio Ghibli animator Makiko Futaki passes away at 58

Studio Ghibli animator Makiko Futaki passes away at 58