We’re back for another look at how the arms and armor of samurai developed, and this time we learn why they ditched their otachi for uchigatana.

Last week, we took a trip through samurai history, examining how the armor worn by Japan’s warriors changed through different eras of Japan’s past. Of course, it wasn’t just the defensive nature of warfare that shifted over time, and Japan’s samurai swords also evolved.

Once again, our guide on this journey is the Fukuoka City Museum’s ongoing Samurai: The Beauty and Pedigree of Warriors exhibit. With nearly 150 pieces on display, there’s a lot to look at, but let’s start in the late years of the Heian period (which lasted from 794 to 1185).

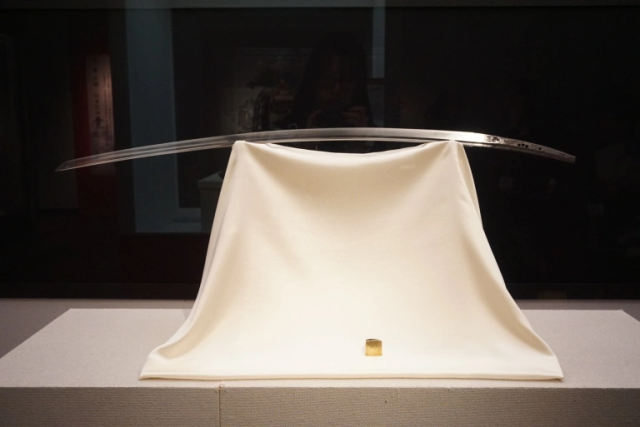

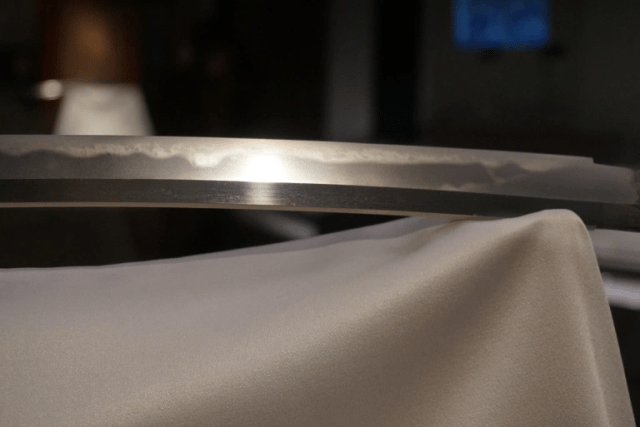

▼ A blade from swordsmith Tomonari of Bizen (present-day Okayama Prefecture), with a protracted curve that starts almost immediately after the hilt.

Despite all the dramatic martial arts movie narration you may have heard about the sword being the soul of the samurai, it wasn’t always their most useful weapon. For several centuries, archery was what set a samurai apart on the battlefield, as conflicts were often fought by well-funded warriors firing arrows at each other from horseback. Eventually, though, commanders started looking for ways for foot soldiers to take down mounted foes, which led to long, slender-curved swords meant to be used to cut the legs of a rider’s horse out from under him. This continued into the early years of the Kamakura period (1185-1333), during which polearms such as the naginata and nagamaki also rose in prominence.

But as you might remember from our discussion of samurai armor evolution, samurai lords began building more and more castles in the years following the Kamakura era. With cavalry ineffective for either side in a siege, foot soldiers became increasingly important, and hand-to-hand fighting became a more prevalent part of military conflicts. Armor became lighter and more form-fitting, since it no longer needed the large gaps between plates that horseback archers required to ride and shoot. In response, swords became larger and heavier, characterized by the weapons called otachi in the Nanbokucho period (1336-1392).

With their curve shifted to the mid-point of the blade, otachi were designed to hack and slash with, since you had to cut through armor and were trying to outright kill your opponent, not simply hurt his horse’s bare shin and render it unable to run.

However, fighting on foot also meant that samurai had to conserve their stamina, and running around swinging bulky otachi for an entire battle wasn’t always the best strategy. So in the Muromachi and Sengoku periods (1336-1600), preferences changed again, with samurai now favoring the shorter, straighter uchigatana. These katana were particularly suited to close combat, with a balance between swiftness and cutting ability. They were also easier to quickly draw from a sheath, enabling them to remain popular even as Japan’s age of armored combat came to a close.

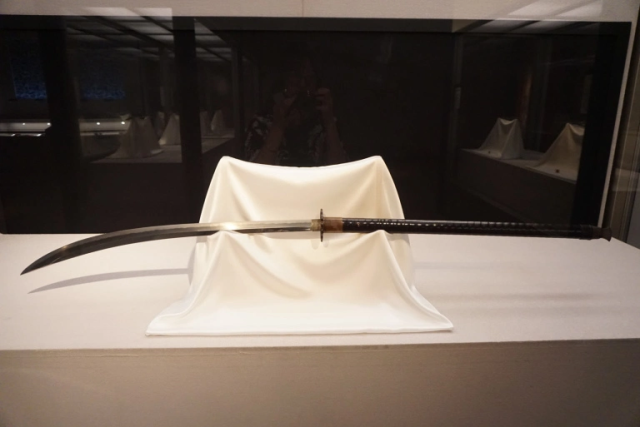

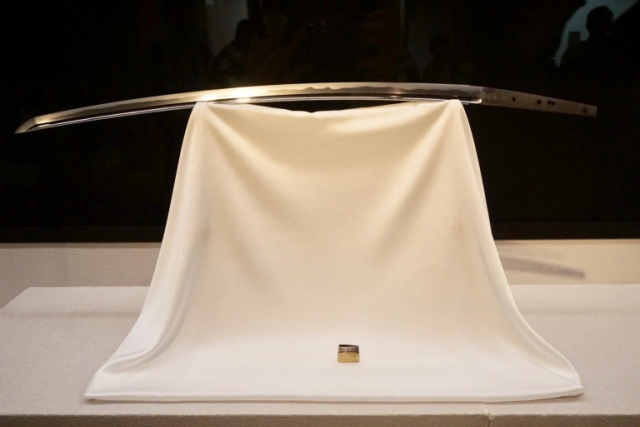

Some otachi which had been forged in earlier times were even modified by their Sengoku period owners. For example, the Heshikiri Hasebe was forged roughly 200 years before it was wielded by warlord Oda Nobunaga, who had its tang (the metal protrusion that extends into the sword’s handle) shortened, brining its size closer to that of an uchigatana.

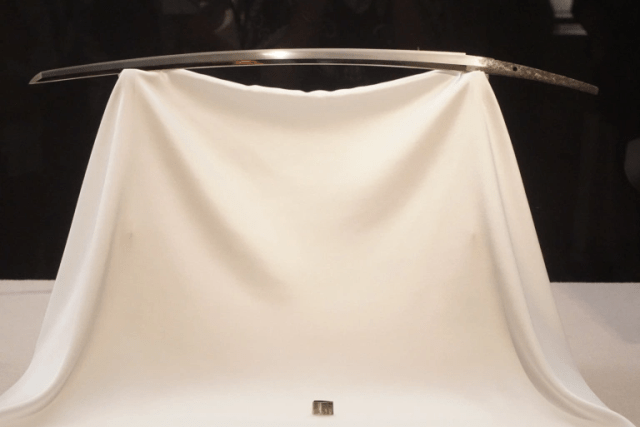

Another unique aspect of the Heshikiri Hasebe is that the entire blade was quenched when it was forged, resulting in dramatic tempering lines across its entire face.

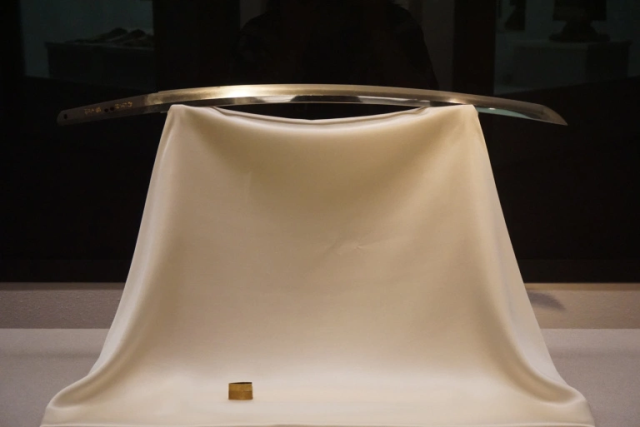

Speaking of tempering marks, the Nikko Ichimonji. A certified Japanese national treasure from the Kamakura period, the Nikko Ichimonji’s has a series of flower petal-shaped temper colorings near its tip.

Also part of the exhibit and another national treasure, at just 54 centimeters (21.3 inches) long the Raikunitoshi is the shortest sword in Japan to bear that distinction.

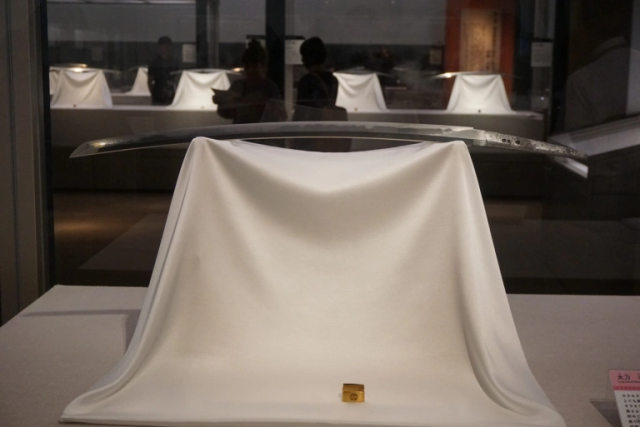

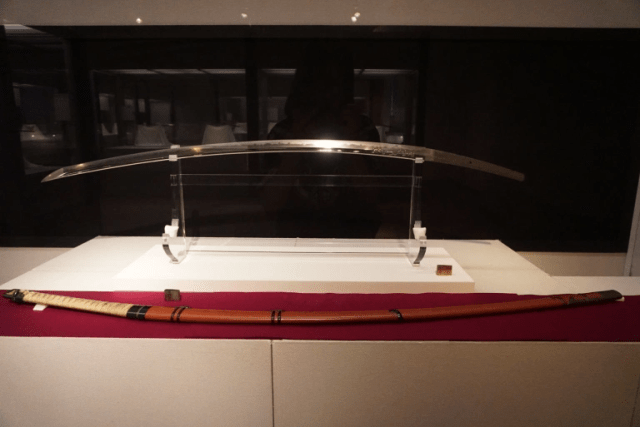

But if you’re of the mind that bigger is always better, the museum is also showing the longest national treasure sword, the 159-centimeter Bishu Osafune Tomomitsu, an intimidating blade forged sometime around 1360, when otachi influences were still being felt.

The exhibit also includes a number of tanto (daggers), with the Taiko Samonji, once again a national treasure, with a crystal-like sparkle historians call jinie.

We also had a chance to look at another piece from master smith Samonji Genkei, who worked during the mid-1300s, in the form of his Yoshimoto Samonji.

However, while the tang bears Samonji’s mark, the blade itself has temper lines quite unlike the jagged patterns regularly associated with his work, leading some to speculate that the sword was retempered by another smith at some point in time.

While the Yoshimoto Samoji was only on display until October 6, there’s still plenty to see in the exhibit, which runs until November 4.

Museum information

Fukuoka City Museum / 福岡市博物館

Address: Fukuoka-ken, Fukuoka-shi, Sawara-ku, Momochihama 3-1-1

福岡県福岡市早良区百道浜3丁目1-1

Open 9:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m.

Closed Mondays

Admission 1,500 yen (US$14)

Museum website

Exhibition website

Photos ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

This hotel has one of the coolest katana collections in Japan, and admission is totally free【Pics】

This hotel has one of the coolest katana collections in Japan, and admission is totally free【Pics】 Dojigiri, the millennium-old katana said to have slain a demon, is now on display in Tokyo【Pics】

Dojigiri, the millennium-old katana said to have slain a demon, is now on display in Tokyo【Pics】 Scholars confirm first discovery of Japanese sword from master bladesmith Masamune in 150 years

Scholars confirm first discovery of Japanese sword from master bladesmith Masamune in 150 years Swords of famous samurai reborn as beautiful kitchen knives from Japan’s number-one katana town

Swords of famous samurai reborn as beautiful kitchen knives from Japan’s number-one katana town Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana, forged by master swordsmith, now on display【Pics】 Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Seaside scenery, history, and so many desserts on Yokohama’s Akai Kutsu【Japan Loop Buses】

Seaside scenery, history, and so many desserts on Yokohama’s Akai Kutsu【Japan Loop Buses】 Should you add tartar sauce to Japanese curry rice? CoCo Ichi makes diners an unusual offer

Should you add tartar sauce to Japanese curry rice? CoCo Ichi makes diners an unusual offer Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day

Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates

Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it Japan’s cooling body wipe sheets want to help you beat the heat, but which work and which don’t?

Japan’s cooling body wipe sheets want to help you beat the heat, but which work and which don’t? Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it

Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it Smash Bros. director Sakurai stabs Kirby in the face, has delicious justification for it

Smash Bros. director Sakurai stabs Kirby in the face, has delicious justification for it Amazing exhibition of Japan’s legendary “cursed katana” is going on right now【Photos】

Amazing exhibition of Japan’s legendary “cursed katana” is going on right now【Photos】 McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Japan’s legendary Brother Katana might not be brothers after all? Investigating the mystery【Pics】

Japan’s legendary Brother Katana might not be brothers after all? Investigating the mystery【Pics】 Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin katana forged based on sword of series’ most merciless villain【Photos】 Demon-slaying Dojigiri, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display at Kasuga Shrine

Demon-slaying Dojigiri, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display at Kasuga Shrine Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo

Legendary crescent moon katana, one of Japan’s Five Swords Under Heaven, now on display in Tokyo Japan is running out of swordsmiths, and a strict apprenticeship requirement is a big reason why

Japan is running out of swordsmiths, and a strict apprenticeship requirement is a big reason why Slice into a traditional sweet range with some of Japan’s most famous swords

Slice into a traditional sweet range with some of Japan’s most famous swords Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana now on display in Tokyo【Photos】

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade katana now on display in Tokyo【Photos】 Amazing exhibition of Japan’s legendary “cursed katana” is going on right now【Photos】

Amazing exhibition of Japan’s legendary “cursed katana” is going on right now【Photos】 Samurai fashion guide – Should you wear your sword blade-up or blade-down?

Samurai fashion guide – Should you wear your sword blade-up or blade-down? Katana of four of Japan’s greatest samurai turned into gorgeous scissors

Katana of four of Japan’s greatest samurai turned into gorgeous scissors Samurai Ninja Museum Tokyo With Experience is true to its name, lets you slice with real katana

Samurai Ninja Museum Tokyo With Experience is true to its name, lets you slice with real katana Genuine Muramasa blade and Muromachi katana on display at Tokyo’s Touken Ranbu store【Photos】

Genuine Muramasa blade and Muromachi katana on display at Tokyo’s Touken Ranbu store【Photos】 Tokyo’s new samurai photo studio sends you to Japan’s feudal era with awesome digital backdrops

Tokyo’s new samurai photo studio sends you to Japan’s feudal era with awesome digital backdrops Foreign tourists pick the top 10 must-visit museums in Japan

Foreign tourists pick the top 10 must-visit museums in Japan Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade sword to be displayed in Tokyo

Real-life Rurouni Kenshin reverse-blade sword to be displayed in Tokyo A roundup of some of this year’s best “Samurai Sanders”: KFC’s mascot in samurai armor【Photos】

A roundup of some of this year’s best “Samurai Sanders”: KFC’s mascot in samurai armor【Photos】

Leave a Reply