“Beating up tea” and college classes and “fixing” things that aren’t broken.

Our Japanese-language reporter Udonko grew up in a small town in east Japan, so when she graduated from high school and moved to Kyoto to start college, she had some adjusting to do. It wasn’t just the transition from small-town to big-city life or the switch from living with her parents to having her own apartment that Udonko had to get used to, though, because there was another set of new challenges waiting for her in Kyoto: how the people there speak Japanese.

The Japanese language has a number of regional dialects. Over time, the style of speaking in Tokyo and east Japan has become what’s considered hyojungo, or “standard Japanese.” On the other hand, the Kansai region, which includes the cities of Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe, has its own dialect, called Kansai-ben.

Unlike, for instance, Chinese dialects, the differences between Japanese dialects aren’t so pronounced that speakers of hyujungo and Kansai-ben can’t generally understand each other pretty easily. Core grammar is basically the same across Japanese dialects, as is almost all vocabulary. However, sometimes the same word, or words that are pronounced the same, can have very different meanings in standard Japanese and Kansai dialect. Here are four that tripped up Udonko, and might do the same to you if you’ve been studying/speaking standard Japanese before arriving in Kansai.

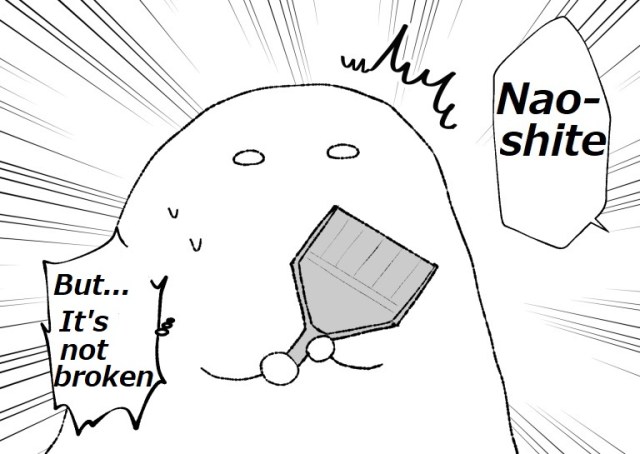

1. naosu

In standard Japanese, naosu means “to fix” or “to repair,” and if you want to make it a command, you say naoshite.

So imagine Udonko’s confusion when one of her art class schoolmates handed her a brush that, to Udonko’s eyes, was in perfect condition, and told her “Naoshite.”

This happened shortly after Undoko had moved to Kyoto, and she was completely stumped as to what her classmate wanted her to do. Was there some hidden defect that she just wasn’t noticing? But then she looked around and saw other people putting their art supplies away. It turns out that in Kansai, naosu can also be used the same way as the word katatzukeru (katatzukete in its command form), which means “to straighten up, put away, or organize” something.

2. -kaisei

Kaisei, written in kanji as 回生, means “regenerate,” “resuscitate,” or “resurrect.” It’s pretty easy to trace why, as 回 means, loosely, “iteration” and 生 means “life.”

As a result, Udonko was pretty shocked when she was having a conversation with a guidance counselor at her new school and the administrator recommended a selection of classes for her ikkaisei, or, to Udonko’s east Japan brain, her “first-time life.”

Was…was Udonko’s guidance counselor telling her that she was going to die? Wait, wait, maybe she was just saying that Udonko was going to meet with some grievous injury, and that these classes would be a manageable study load as she…regenerated? Was the school going to teach her how to regrow parts of her body?!?

The truth, though, was far less morbid/awesome. The counselor was simply giving Udonko a list of recommended classes to take as a first-year student. In standard Japanese, a first-year student is called an ichinensei (literally “year-one life”). In Kansai, though, first-year university students can also be called ikkaisei, because it’s their first time making an iteration around that specific school’s academic year.

3. sara

Depending on where/how it’s used in a sentence, sara has a couple of potential meanings, even in standard Japanese. When it’s used as a verb, though, sara generally means a “plate” or “dish,” as in the kind you eat off of.

Yet when Udonko, who’d just finished putting a new protective sheet on her tablet, showed off the recently reinforced gadget to one of her new Kansai friends, that friend smiled and said, “Oh, wow! You made it sara!” which Udonko took to mean “Oh, wow! You made it a plate!”

Kansai in general is known for having a rich culinary culture, and that goes double for Kyoto. But Udonko couldn’t imagine that when it’s time to eat in Kansai, people just lay their electronic devices down on the table and put their food on the screen, regardless of whether or not it’s outfitted with a protective sheet.

Actually, though, in Kansai dialect sara is a way of saying “new” or “a new one.” Unlike the above examples of naosu and kaisei, where the same words can have different meanings depending on the region, Kansai’s “new” sara is a homonym to the “plate” sara, but it’s one that momentarily caused Udonko’s brain to bug out all the same.

4. cha wo shibaku

Udonko had one more food/beverage-related linguistic culture shock after arriving in Kyoto. Cha means “tea,” and shibaku means “to hit, strike, or beat.” So Udonko was baffled, and a little frightened, when a friend nonchalantly suggested that they go cha wo shibaku, or “Beat up some tea.”

The gap between Udonko’s violent vocabulary and cheerful demeanor was unnerving…until Udonko learned that, in Kansai, cha wo shibaku is an alternate way of saying ocha suru, the standard Japanese way of saying “have some tea,” and by extension “take a break and have something to drink (and probably some snacks or sweets).”

▼ It’s worth noting, too, that cha wo shibaku doesn’t carry the same rowdy tone of saying “Let’s crush some beers!” in English, and so Udonko and her friend’s “tea-beating” session ended with no cups shattered or desserts thrown across the room.

Again, Japanese dialects aren’t so different that people from different parts of the country face an actual language barrier, but that makes it all the more jarring when situations like these do pop up. There were far from the last bit of Kansai dialect Udonko encountered for the first time while living in Kyoto, but they’re the ones that left the deepest impression on her, so keep an ear out for them if you’re in region, and keep them in your back pocket if you want to sprinkle them into conversation with your Kansai-ben friends.

Illustrations ©SoraNews24

Top photo: Pakutaso

Insert photo: Pakutaso

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he once confused his hyojungo-speaking coworkers by saying “tawan.”

Taking the Kyoto overnight bus for the first time

Taking the Kyoto overnight bus for the first time Can Kyoto supermarket takeout let you enjoy the local cuisine without fancy restaurant prices?

Can Kyoto supermarket takeout let you enjoy the local cuisine without fancy restaurant prices? Kyoto’s “ikezu” culture of backhanded compliments explained in hilarious souvenir sticker series

Kyoto’s “ikezu” culture of backhanded compliments explained in hilarious souvenir sticker series Apprentice geisha fire drill in Kyoto leaves Internet charmed and chuckling【Video】

Apprentice geisha fire drill in Kyoto leaves Internet charmed and chuckling【Video】 Our search for Kyoto Station’s cheapest souvenir reveals a surprisingly sweet find

Our search for Kyoto Station’s cheapest souvenir reveals a surprisingly sweet find Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model

Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model Japan Snow Battle Federation looking to make snowball fights Olympic event

Japan Snow Battle Federation looking to make snowball fights Olympic event Japanese Prime Minister once criticized deploying military to fight Godzilla

Japanese Prime Minister once criticized deploying military to fight Godzilla Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism”

Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism” Tokyo Station staff share their top 10 favorite ekiben

Tokyo Station staff share their top 10 favorite ekiben Real-life Spirited Away train line found in Japan?

Real-life Spirited Away train line found in Japan? The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens

Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens Playing Switch 2 games with just one hand is possible thanks to Japanese peripheral maker

Playing Switch 2 games with just one hand is possible thanks to Japanese peripheral maker Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】

Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】 Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Why you shouldn’t call this food “Hiroshimayaki” if you’re talking to people from Hiroshima

Why you shouldn’t call this food “Hiroshimayaki” if you’re talking to people from Hiroshima Kyoto accidentally calls all old people “terrible drivers”【Why Does Engrish Happen in Japan?】

Kyoto accidentally calls all old people “terrible drivers”【Why Does Engrish Happen in Japan?】 Takoyaki…inarizushi? New fusion food boggles the mind in Japan

Takoyaki…inarizushi? New fusion food boggles the mind in Japan Is Kyoto less crowded with tourists after China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning?【Photos】

Is Kyoto less crowded with tourists after China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning?【Photos】