Do you find yourself living in the now, enjoying the time and money you have presently without worrying so much about putting away for the future? According to one economist, the language you speak may play a role in how well you’re able to save money. Speakers of Norwegian or Japanese, for example, are more likely to save more money per year, and have more money saved up by the time they retire, than are speakers of, say, English or Greek.

But what is it exactly that differs between these languages, and most importantly, what relation does that have to money?

As it turns out, our language has an effect on the way we see the world. To give a simple example, in English, we can refer to a specific sibling as either “my brother” or “my sister” without consideration for their age in relation to ourselves. But in Japanese, there is no singular word for “brother” or “sister”, so speakers must convey whether the sibling they are referring to is an older brother or sister (ani or ane, respectively) or a younger brother or sister (otouto or imouto), even in the case of twins. Then there are the words used for other people’s siblings, but that’s another story…

While English speakers might not see the necessity of always indicating whether a sibling is older or younger, in a society like Japan that places more emphasis on age and hierarchy, it’s only natural to make that distinction.

▼I may be only four minutes older, but I’m still your elder!

In this same way, economist Keith Chen believes that whether or not a language differentiates between present and future tense has an effect on how we view time and, in turn, how likely we are to put money aside for the future.

In English, we have different verbs to help us distinguish between past, present, and future. Using Chen’s example, we would say, “It rained yesterday”, “It’s raining today”, or “It will rain tomorrow”, to indicate when exactly the rain has happened, or will happen. But in futureless languages such as German or Japanese, there is no future tense. To say in Japanese, “Ame ga furu” translates simply as “It rains”. In order to indicate the future tense, you need to attach a time-related word like “tomorrow” (ashita) to indicate when the rain will happen, thus making the sentence, “Tomorrow it rains” (Ashita ame ga furu).

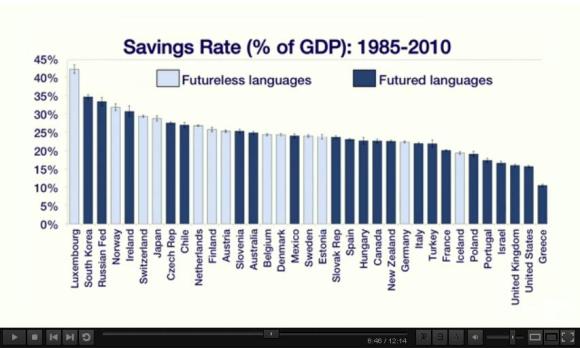

Chen theorizes that the lack of a future tense makes the speaker feel like the future is closer to the present, while the presence of a future tense does the opposite, making the speaker more aware and concerned about the now, as opposed to the later. He claims in his research to have found a correlation between speakers of futureless languages and their likelihood to be better savers.

▼Futureless languages display higher average savings overall when compared to futured languages

Even after controlling for various cultural, economical, and religious factors, Chen still found that futureless language speakers are 30 percent more likely to save in any given year, and are going to retire with about 25 percent more in savings.

He admits his theory that there is a relation between language and one’s inclination to save is a fanciful one, but claims he has yet to find anything to disprove it. If you’re starting to think it might be in your best interest to begin studying a futureless language, we won’t stop you – being multilingual is awesome, and does have many other benefits, whether this includes Chen’s theory or not. But if you are mostly just concerned about your future savings, it might be easier to change your attitude and thoughts about time instead.

Source: TED Talks (DigitalCast) via NAVER Matome

Featured image: David Castillo Dominici at FreeDigitalPhotos

If you want to explore the Hermit Kingdom of North Korea, there’s an app for that

If you want to explore the Hermit Kingdom of North Korea, there’s an app for that Japanese book “nekotan” teaches foreign language the best way possible: by talking about cats

Japanese book “nekotan” teaches foreign language the best way possible: by talking about cats When “yes” means “no” — The Japanese language quirk that trips English speakers up

When “yes” means “no” — The Japanese language quirk that trips English speakers up Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them

Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them Sony unveils bizarre new TV remote control with built-in speaker, met with confusion and LOLs

Sony unveils bizarre new TV remote control with built-in speaker, met with confusion and LOLs How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan

How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration

Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide

Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir

New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir New Nintendo Lego kit is a beautiful piece of moving pixel art of Mario and Yoshi【Photos】

New Nintendo Lego kit is a beautiful piece of moving pixel art of Mario and Yoshi【Photos】 Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys

Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience

Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience 10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan

10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan McDonald’s adds new watermelon frappe and fruity macaron to its menu in Japan

McDonald’s adds new watermelon frappe and fruity macaron to its menu in Japan “The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】

“The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】 Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan

Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters

Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches

McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous?

Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous? Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not

Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists

Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners

To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear

Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka

Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model

Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose

Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】

Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】 Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Japanese students despair over the many, MANY ways you can describe a dead flower

Japanese students despair over the many, MANY ways you can describe a dead flower The Japanese you learn at school vs the Japanese used in Japan【Video】

The Japanese you learn at school vs the Japanese used in Japan【Video】 Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker

Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese

RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese Westerners in Japan – do they really ALL speak English? 【Video】

Westerners in Japan – do they really ALL speak English? 【Video】 Adult Cream Pie coming to McDonald’s Japan

Adult Cream Pie coming to McDonald’s Japan “Japanese English” can baffle native English speakers — but what about Korean speakers? 【Video】

“Japanese English” can baffle native English speakers — but what about Korean speakers? 【Video】 Nine reasons why Japanese men hesitate to say “I love you”

Nine reasons why Japanese men hesitate to say “I love you” Japanese student protesters announce “WE WILL STOP!!!!” in English on Twitter, get clowned for it

Japanese student protesters announce “WE WILL STOP!!!!” in English on Twitter, get clowned for it Japanese Twitter user embarrassed to learn why American friend is studying Japanese, not Chinese

Japanese Twitter user embarrassed to learn why American friend is studying Japanese, not Chinese Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 Peace-making Great Pyrenees is everything the world needs this year 【Video】

Peace-making Great Pyrenees is everything the world needs this year 【Video】 Nihon-no: Is an entirely English-speaking village coming to Tokyo?

Nihon-no: Is an entirely English-speaking village coming to Tokyo? Looking for a job in Japan? New “Sugoi Kawaii” maid cafe in Akihabara now hiring foreigners!

Looking for a job in Japan? New “Sugoi Kawaii” maid cafe in Akihabara now hiring foreigners! Hugh Jackman stars, sings J-pop cover, and speaks Japanese in ads for Toyota【Videos】

Hugh Jackman stars, sings J-pop cover, and speaks Japanese in ads for Toyota【Videos】

Leave a Reply