And even though there are some staples on the menu throughout the nation, what goes into those staples also varies!

New Year’s is a highly auspicious time in Japan, a time when you want to keep a peaceful, quiet home to welcome any visiting spirits and promote good fortune for the year. That means there are some rules for the first three days of the New Year that, if broken, could result in bad luck.

Two of those involve cooking or eating–no boiling water over a fire and no eating four-legged creatures–and another says no cleaning, so naturally, that sort of precludes anyone from being able to cook their own meals in the first three days of the year. Luckily, there’s a tradition for that: cooking (or buying) a boatload of food before the New Year and eating it over three days!

New Year’s food is called “osechi ryori” and is composed of dozens of different small dishes of vegetables and seafood, but as it turns out, the dishes used can vary greatly by region. Food production company Kibun Foods released its annual “Oshougatsu Hyakka” magazine, which is all about New Year’s and osechi, and this year’s included the results of a survey about what people eat on New Year’s. The results were pretty interesting!

The survey asked 5,875 married women from all 47 prefectures between the age of 20 and 60 about what they prepare for osechi. 49 answers were supplied, but there was a definite most popular dish: kamaboko, or steamed and seasoned fish paste. 83.2 percent of respondents said they included it in their osechi meals.

▼ Shown here as the pink and white squares

In the second position was ozoni, a soup of mochi and vegetables. Mochi is a symbolic food for New Year’s, but it’s a dangerous ingredient in soup; when not chewed properly, slippery mochi can be a choking hazard. Still, that doesn’t deter people from eating it; 73.5 percent of respondents said they prepare it every year.

Also on the list were black soybeans cooked with sugar and soy sauce in third place (68.9 percent); datemaki, a rolled omelet mixed with fishpaste, in fourth (65.8 percent); and kazunoko, herring roe, in fifth (58.6 percent).

▼ Black soybeans

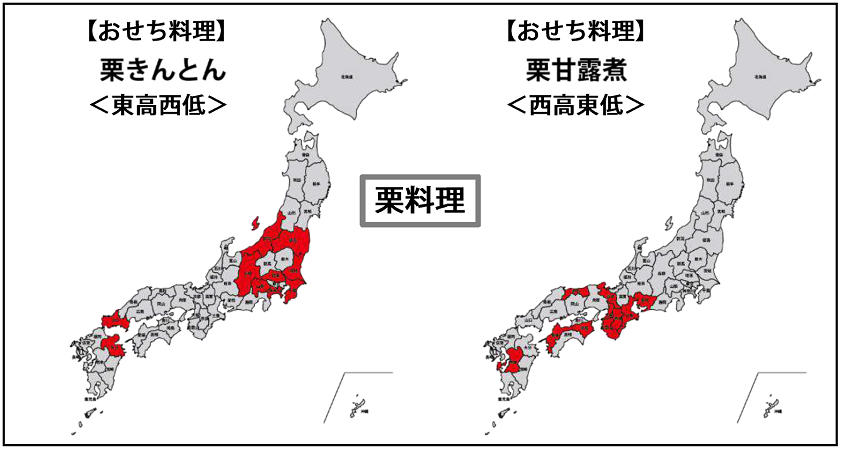

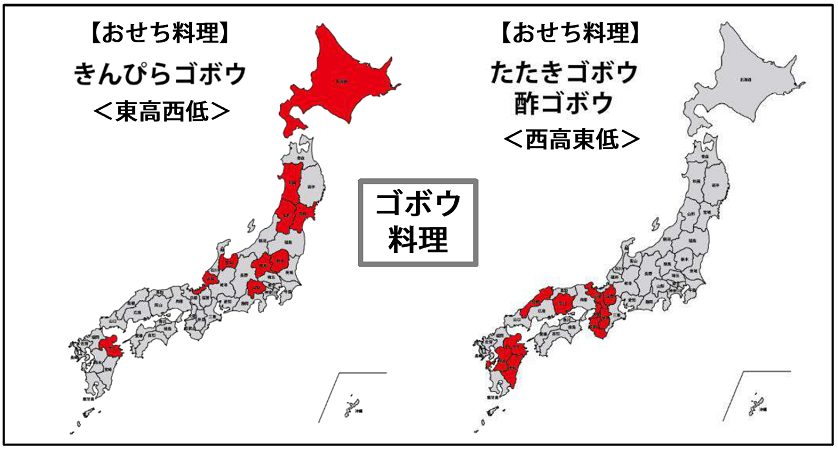

While the top three are prepared all across the nation, after that, the popular dishes vary by region. For example, the sixth most popular osechi dish, according to the survey, mashed sweet potatoes with chestnuts (kurumi kinton), is primarily eaten in eastern Japan, while western Japan seems to prefer candied chestnuts.

▼ Prefectures that eat kurumi kinton on the left, and those that eat candied chestnuts on the right

Like chestnuts, burdock roots (gobo) are considered a lucky food in Japan and are also a popular part of osechi cuisine. But how they’re prepared is different depending on the region. In eastern Japan, they prefer to stir fry their burdock root with soy sauce and sugar (a dish known as kinpira gobo), but in western Japan, they prefer it to be seasoned with sesame or vinegar.

▼ Prefectures that eat kinpira gobo on the left, and those that eat sesame or vinegar gobo on the right

Even, ozoni, a nationwide favorite, has its own regional variations. For example, according to the survey, the way you cut the mochi that goes into it differs. In east Japan, they cut it into rectangles, but in west Japan, they prefer it to be round.

▼ Red likes them round, yellow likes them rectangular

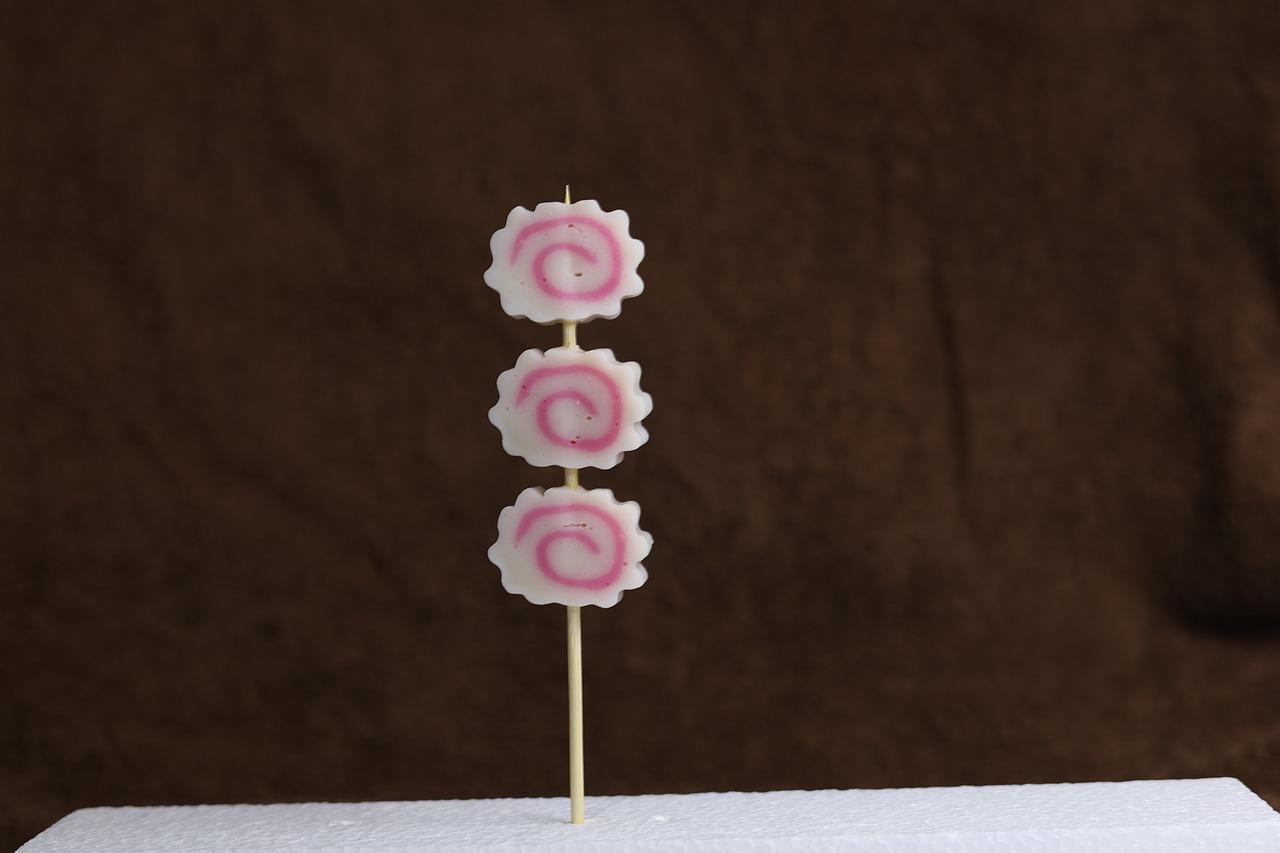

The type of fish paste used differs too; narutomaki, the kind that comes with a swirl in the middle (as shown below), is more popular in east Japan, but west Japan seems to like kamaboko, which is usually arch-shaped.

▼ Narutomaki

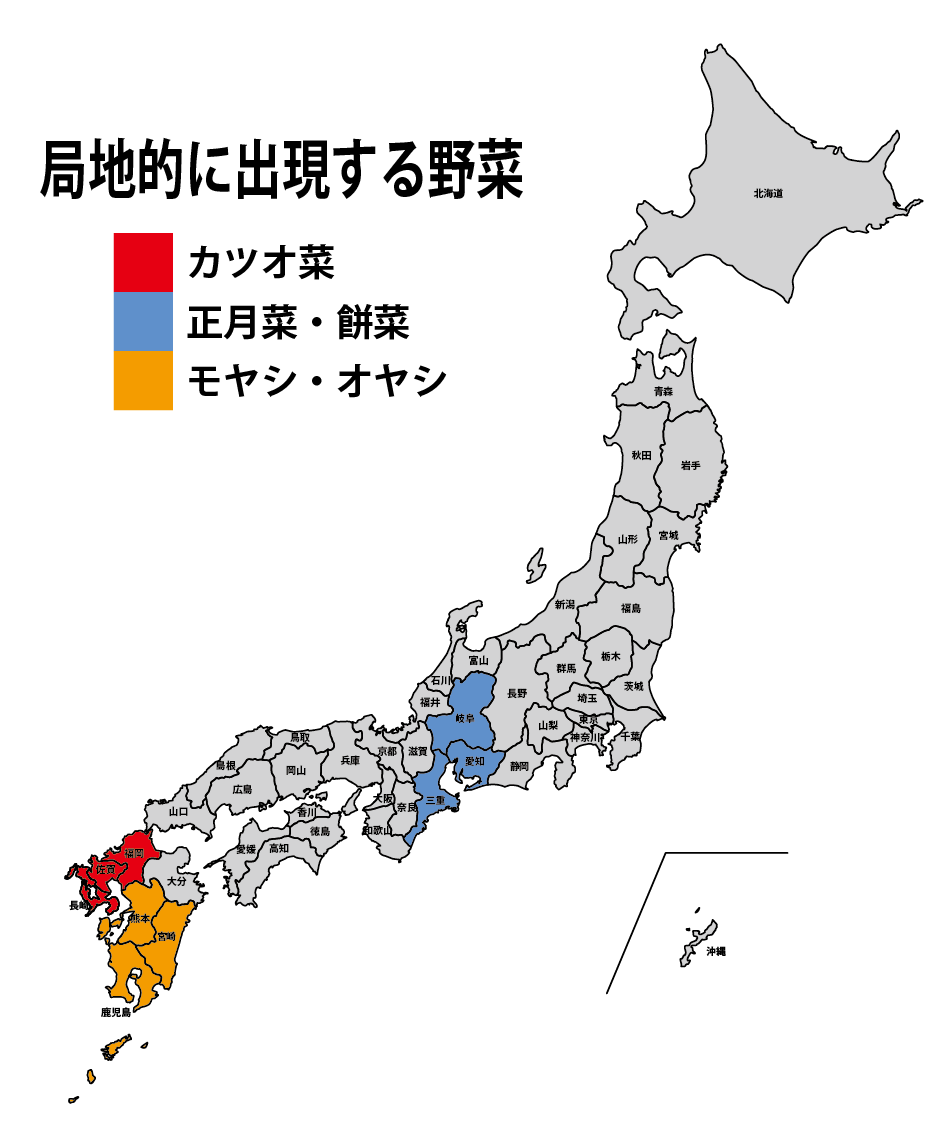

The survey also revealed that region dictates what seafood goes in too; in the east, they like to add in salmon roe, but in the west, shrimp is more popular. Even the vegetables used in ozoni (besides the most popular root vegetables) vary by region! For example, Kyushu alone is divided by north and south. The north likes to add a leafy green field mustard known as katsuona, but the south likes to use bean sprouts.

▼ Red is for katsuona, yellow is for bean sprouts, and blue represents another field mustard variety, shogatsuna.

It’s interesting to see how many varieties of osechi there are all across the country. Sadly, osechi is losing popularity among younger people for a number of reasons, not least of which is the cost of purchasing a proper osechi box to last three days for all the people in your household (or all the ingredients needed to make one).

Still, another recent survey indicated that though people are celebrating the New Year differently in the age of COVID-19, osechi ryori still plays a major role–whether cooked or purchased–so we could still see this food tradition continue on for years to come.

Source: @Press

Top image: @Press

Insert images: @Press, Pakutaso (1, 2), Pixabay (1, 2, 3, 4)

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Deadly New Year mochi strikes again, hospitalizing 19 and resulting in 4 deaths

Deadly New Year mochi strikes again, hospitalizing 19 and resulting in 4 deaths Japan’s most dangerous New Year’s food causes death once again in Tokyo

Japan’s most dangerous New Year’s food causes death once again in Tokyo Mochi continues to be Japan’s deadliest New Year’s food, causes two deaths in Tokyo on January 1

Mochi continues to be Japan’s deadliest New Year’s food, causes two deaths in Tokyo on January 1 Celebrate New Years in Pokémon style — with a monster ball filled with traditional osechi food!

Celebrate New Years in Pokémon style — with a monster ball filled with traditional osechi food! Mochi, the danger of Japanese New Year’s, claims another life, rushes many to hospital

Mochi, the danger of Japanese New Year’s, claims another life, rushes many to hospital Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service returns to theaters with first-ever IMAX screenings and remaster

Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service returns to theaters with first-ever IMAX screenings and remaster Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Pizza Hut adds burgers to its menu in Japan for a limited time

Pizza Hut adds burgers to its menu in Japan for a limited time Japan’s bathhouse-themed bar replaces hot water with unlimited alcohol

Japan’s bathhouse-themed bar replaces hot water with unlimited alcohol In Japan, you can buy ramen noodles made by prison inmates, but is it any good?【Taste test】

In Japan, you can buy ramen noodles made by prison inmates, but is it any good?【Taste test】 McDonald’s Japan adds new “Grand” size to its menu…but are the portions really supersize?

McDonald’s Japan adds new “Grand” size to its menu…but are the portions really supersize? Hello Kitty, My Melody sukajan jackets combine symbols of Japan traditional, old-school, and cute

Hello Kitty, My Melody sukajan jackets combine symbols of Japan traditional, old-school, and cute Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Japan’s deadliest food claims more victims, but why do people keep eating it for New Year’s?

Japan’s deadliest food claims more victims, but why do people keep eating it for New Year’s? You can enjoy traditional Japanese New Year’s osechi eats on a budget with Lawson Store 100

You can enjoy traditional Japanese New Year’s osechi eats on a budget with Lawson Store 100 Japan’ deadliest New Year’s food may be even more dangerous in 2021 due to the coronavirus

Japan’ deadliest New Year’s food may be even more dangerous in 2021 due to the coronavirus Six non-traditional osechi New Year’s meals in Japan

Six non-traditional osechi New Year’s meals in Japan Ginza Cozy Corner is back with their traditional “osechi” style cake set and more

Ginza Cozy Corner is back with their traditional “osechi” style cake set and more The meaning of the mandarin and 6 other Japanese New Year traditions explained

The meaning of the mandarin and 6 other Japanese New Year traditions explained Traditional Japanese cuisine meets Star Wars for New Year’s osechi celebration meals

Traditional Japanese cuisine meets Star Wars for New Year’s osechi celebration meals Awesome Pokémon osechi New Year’s meals elegantly blend Japan’s traditional and pop culture

Awesome Pokémon osechi New Year’s meals elegantly blend Japan’s traditional and pop culture Survey reveals how Japanese people plan to spend the 2023 New Year’s holiday

Survey reveals how Japanese people plan to spend the 2023 New Year’s holiday Celebrate the New Year with a special and limited edition Barbie bento box of New Year foods

Celebrate the New Year with a special and limited edition Barbie bento box of New Year foods Japanese osechi New Year’s meal lucky bag gives us way more than we bargained for

Japanese osechi New Year’s meal lucky bag gives us way more than we bargained for No need to be lonely at New Year’s with Japan’s new one-person osechi set【Taste test】

No need to be lonely at New Year’s with Japan’s new one-person osechi set【Taste test】 Lucky Japanese new year ice cream! Baskin-Robbins’ flavor inspired by traditional osechi cuisine

Lucky Japanese new year ice cream! Baskin-Robbins’ flavor inspired by traditional osechi cuisine Here’s what our bachelor writers ate over the New Year’s holiday in Japan

Here’s what our bachelor writers ate over the New Year’s holiday in Japan More people travelling in Japan for the New Year’s holiday than last year, survey says

More people travelling in Japan for the New Year’s holiday than last year, survey says Six things to avoid doing in the first three days of the Japanese New Year to have the best luck

Six things to avoid doing in the first three days of the Japanese New Year to have the best luck