A Tokyo subway commute daydream turns into a ride to the end of the line.

In Japan, the in-station announcements for departing trains identify them by the last station they’ll be stopping at, which usually means the last stop of the line. For example, every workday morning our Japanese-language reporter Mariko Ohanabatake gets on a Toei Shinjuku Line subway train that the announcement says is “bound for Hashimoto,” but she always gets off way before that, at Shinjuku-sanchome Station, the downtown stop that’s closest to SoraNews24 HQ.

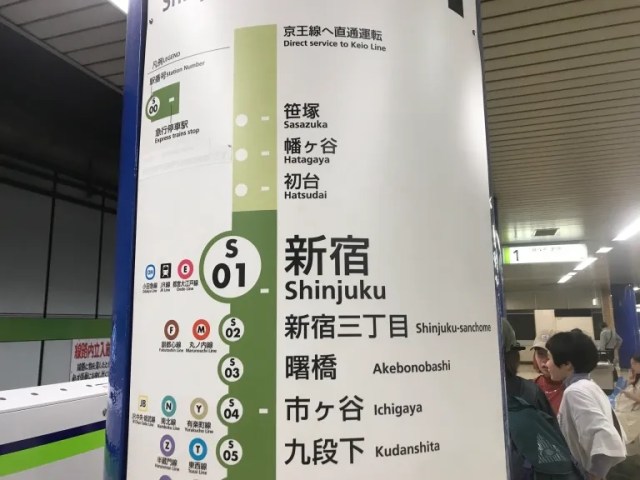

▼ 各駅 橋本 = Local train bound for Hashimoto, as seen on Mariko’s morning commute train

But after years of riding the for-Hashimoto train, Mariko couldn’t help asking herself a question: What’s Hashimoto like? So on a recent morning, Mariko opted out of working in the office to do some field work. Instead of getting off the train at Shinjuku-sanchome, she stayed on and kept riding it until the end of the line.

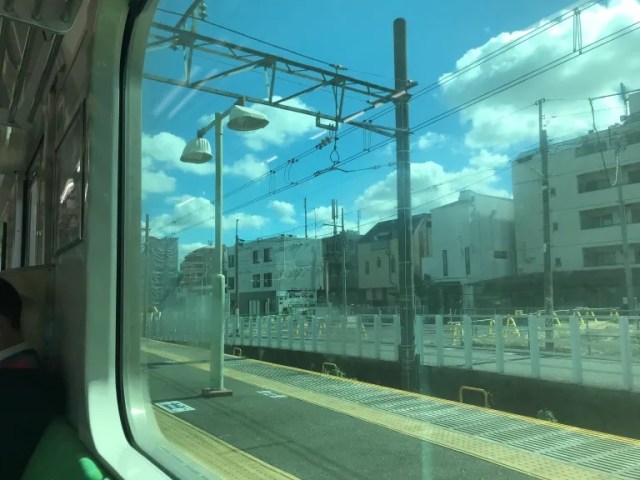

The next stop after Shinjuku-sanchome is Shinjuku Station, and after the Toei Shinjuku Line blends seamlessly into the Keio Sagamihara Line. That’s also the point where the line switches from subterranean to above-ground, and Mariko felt a joyous sense of liberation as her train broke free to the surface and natural sunlight filled the car.

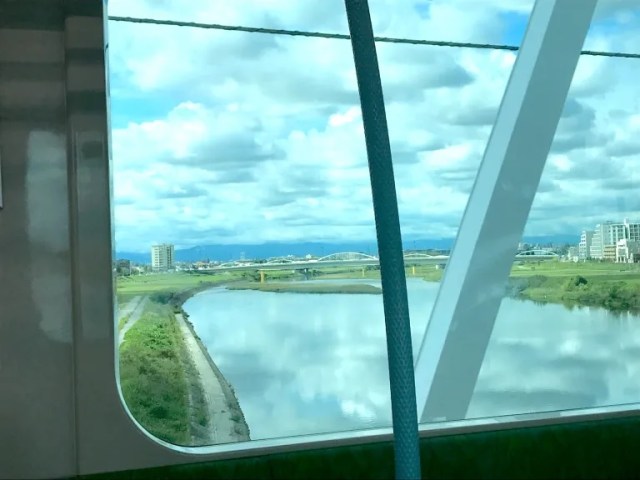

Once you’re past Shinjuku Station, you’re beyond the Yamanote loop line that more-or-less marks the most congested part of downtown Tokyo. As the train continued on its southwestern route, Mariko started seeing fewer skyscrapers and more greenery, including a lovely view of the Tamagawa River a little before Keio Inadazutsumi Station.

▼ The river’s tranquil waters formed a mirror, reflecting the clouds of the autumn sky.

Smaller neighborhoods mean smaller crowds, and with Mariko now heading opposite the direction of the morning commuting rush, there were plenty of empty seats on her train, a surreal change from the packed conditions she usually sees it under on her way to work.

With a spot to sit, warm sunshine, and the rhythmic rocking of the rails, Mariko was unable to resist indulging in one of Japan’s most restorative of pastimes: the train nap.

Waking up a while later, but still far from her destination, Mariko began to envision what Hashimoto Station would be like. Considering how the scenery outside was becoming less and less urban the farther she got away from Tokyo, she imagined that it must get positively bucolic by the time you’re in Hashimoto.

As Mariko started to get close to the end of the line, though, something she hadn’t expected happened.

The stations started gradually getting bigger, and the number of passengers getting on the train increased too.

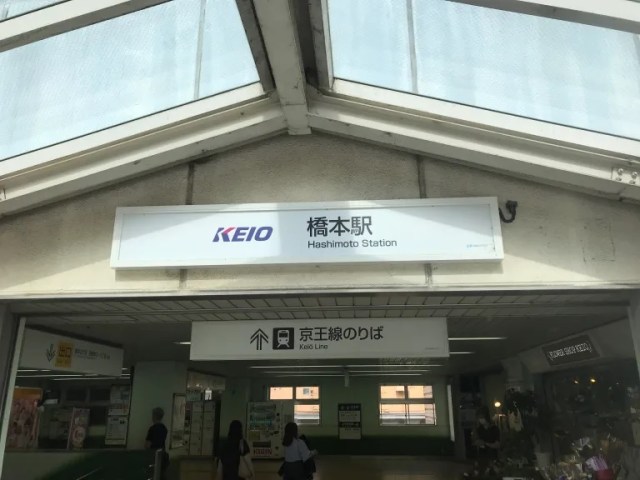

Looking out the windows, she started seeing more multi-story apartment complexes and shopping centers, and when she finally got to Hashimoto Station, it was a modern, well-equipped facility.

Inside the station building there’s a 7-Eleven, a capsule toy shop…

…a 3 Coins 300 yen shop…

…a bookstore…

…and even a mini satellite shop for the Keio department store.

Outside the station were even more shops and restaurants, with branches of Uniqlo and Mujirushi, 100 yen shop Seria, and cafes like Dotour and Starbucks.

Mariko hadn’t been expecting this, but it’s actually very much in keeping with how Japanese cityscapes have developed. Geographically speaking, train/subway lines are just narrow lines, but the way they influence development is actually a series of circles, with the stations along the way at their centers.

Because of the announcements she hears on her morning commutes, Mariko had always thought of Hashimoto Station as the end of the Toei Shinjuku/Keio Sagamihara Line. However, Hashimoto Station is also part of the JR Yokohama and JR Sagami Lines. That means that not only can you take the train from Hashimoto to Shinjuku without transferring, you can take it to Yokohama Station, in the center of Japan’s second-largest city, without transferring too, and the JR Sagami Line also runs through Atsugi and Ebina, two of the larger cities in Kanagawa Prefecture, Tokyo’s neighbor to the south/west.

It’s around 50 minutes from Hashimoto to Shinjuku, and only 40 to Yokohama. With “about an hour” being considered a reasonable commute by most Japanese people, that makes Hashimoto a viable place to live for people working/going to school in the two biggest cities in the country. Hashimoto’s out-of-the-way, end-of-the-line position means it might not attract enough visitors for flashy entertainment options, but the commuter access means it does have enough residents to support plenty of everyday necessity shops and reasonably priced restaurants/takeout places, all with lower housing costs than neighborhoods closer to central Tokyo or Yokohama.

So in the end, Hashimoto wasn’t the isolated-in-the-countryside sort of station that Mariko had been fantasizing about, but it’s actually a pretty decent place to live in the real world.

Photos © SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

End-of-the-Line Exploring in Japan: Tokyo’s Mita Line can give you all the nothing you want【Pics】

End-of-the-Line Exploring in Japan: Tokyo’s Mita Line can give you all the nothing you want【Pics】 Tokyo’s new Keio Liner train debuts next month with special features and reserved seating

Tokyo’s new Keio Liner train debuts next month with special features and reserved seating One of Tokyo’s busiest subway lines is adding women-only cars

One of Tokyo’s busiest subway lines is adding women-only cars These are Tokyo train lines people most want to live along【Survey】

These are Tokyo train lines people most want to live along【Survey】 Tokyo train company makes sweet addition to stations so that birds can keep their nests in them

Tokyo train company makes sweet addition to stations so that birds can keep their nests in them Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino The fish in rural Fukui that rivals Japan’s most auspicious sea bream

The fish in rural Fukui that rivals Japan’s most auspicious sea bream Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels

Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results

Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results The town with Japan’s best castle also has one of Japan’s best breakfasts. Here’s where to eat it

The town with Japan’s best castle also has one of Japan’s best breakfasts. Here’s where to eat it Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now

Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now Can we be just like Shohei Ohtani on a budget with a Hello Kitty cap?

Can we be just like Shohei Ohtani on a budget with a Hello Kitty cap? Mega-hit Japanese boy band Arashi is disbanding

Mega-hit Japanese boy band Arashi is disbanding How to make curry in a rice cooker with zero prep work and no water[Recipe]

How to make curry in a rice cooker with zero prep work and no water[Recipe] Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says What’s it like traversing Tokyo using only wheelchair accessible routes?

What’s it like traversing Tokyo using only wheelchair accessible routes? Commuter chaos around Tokyo during peak hour after Typhoon Trami hits Japan 【Pics & Video】

Commuter chaos around Tokyo during peak hour after Typhoon Trami hits Japan 【Pics & Video】 Station of despair: What to do if you get stuck at the end of Tokyo’s Chuo Rapid Line

Station of despair: What to do if you get stuck at the end of Tokyo’s Chuo Rapid Line Woman suffers burns after aluminium can explodes at Shinjuku Station

Woman suffers burns after aluminium can explodes at Shinjuku Station The 51 Busiest Train Stations in the World– All but 6 Located in Japan

The 51 Busiest Train Stations in the World– All but 6 Located in Japan A visit to Japan’s train station that looks like a spaceport in the middle of nowhere【Photos】

A visit to Japan’s train station that looks like a spaceport in the middle of nowhere【Photos】 Tokyo’s busiest train line to be partially shut down this weekend as part of Shibuya renovations

Tokyo’s busiest train line to be partially shut down this weekend as part of Shibuya renovations Taste the floor of a Japanese train station with new limited-edition chocolates from Tokyo Metro

Taste the floor of a Japanese train station with new limited-edition chocolates from Tokyo Metro Tokyo starts massive renovation project for entrances to the world’s busiest train station

Tokyo starts massive renovation project for entrances to the world’s busiest train station Skynet sends a Terminator to Tokyo’s Shinjuku Station to future-freak-out commuters【Photos】

Skynet sends a Terminator to Tokyo’s Shinjuku Station to future-freak-out commuters【Photos】 Train otaku say this is the narrowest train station platform in Japan

Train otaku say this is the narrowest train station platform in Japan Navigate your way through Japan’s busiest train stations with Google Street View

Navigate your way through Japan’s busiest train stations with Google Street View We visit Tokyo Station…outside of Tokyo

We visit Tokyo Station…outside of Tokyo These are the 11 most crowded trains in Japan…and surprise! They’re all in the Tokyo area

These are the 11 most crowded trains in Japan…and surprise! They’re all in the Tokyo area