Journey into the history of a 1,000-year-old tradition to uncover why this dangerous delicacy continues to have its place on the dinner table.

New Year’s marks an important cultural shift for Japanese people. Everything good and bad that has happened throughout the year resets as the new year begins, representing a personal rebirth and giving everyone a fresh start. In hopes of inviting good fortune for the year ahead, many traditions have been introduced and continue to remain in Japanese culture. One of these traditions, while well-intentioned, involves a lethal risk that has persisted for centuries: the eating of mochi (glutinous rice cakes).

This tradition of consuming mochi originated from the simple act of eating rice in order to gain vitality for the coming year. Rice has always been regarded as sacred in Japan, containing divine energy and life-giving properties. Yet this very same rice, in the form of mochi, is now regarded as one of Japan’s most dangerous foods.

▼ Delicious but deadly

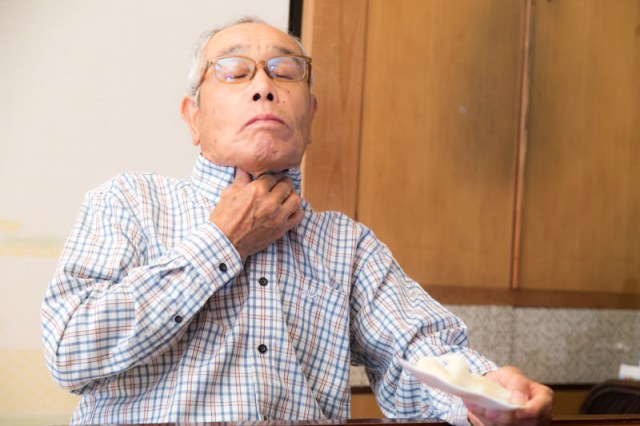

Due to its sticky and chewy texture, if the piece of mochi you swallow is too large, it can lead to choking, asphyxiation, and ultimately death. The Tokyo Fire Department announced that this year between New Year’s Day and 3 p.m. on January 2 seven people were taken to hospital for choking on mochi. Among these seven people, two elderly gentlemen passed away, one in his 70s and the other in his 80s.

Knowing that it can be such a lethal food, especially when you don’t have as many teeth to chew it sufficiently before swallowing, why is it that Japanese people continue to put their lives on the line by eating mochi?

Nowadays, mochi can come in many forms, but traditionally New Year’s was celebrated with a type called kagami mochi. While it can have different levels of decoration, at its base there are two round rice cakes stacked with the smaller one on top of the larger one. The name “kagami” (mirror) comes from the shape of these rice cakes, which was inspired by ancient bronze mirrors. These mirrors were thought to house spirits and the two of them together represent elements like the sun and moon, or yin and yang, and signifies harmony and good fortune.

Japanese people still continue to put out kagami mochi as it serves as a vessel for Toshigami, the Shinto Year God, and is thought to bring blessings and prosperity. When Toshigami visits he also grants each person a new year of life in the form of a year spirit, or toshidama. Over time, this became otoshidama, the tradition of giving money to children for New Year’s.

In order to welcome Toshigami into their homes, Japanese would traditionally clean their houses from mid-December, generally finishing around December 28. They would also decorate with other items such as kadomatsu, a decorative display of pine and bamboo cuttings. Pine trees, being evergreen and having strong vitality and rapid growth, have long symbolized longevity and auspiciousness.

The period during which the kadomatsu is displayed is known as matsu no uchi, at the end of which Toshigami will leave the house. The kagami mochi offering becomes imbued with blessings from the deity and consuming it is believed to transfer the god’s power and good fortune to those who eat it. This is done through a tradition called kagami biraki, literally meaning “mirror opening”, when the hard kagami mochi is broken into smaller pieces with a wooden mallet or by hand.

▼ Smash up those divine blessings! What could go wrong?

The use of sharp objects, such as knives, and using words like “cut” or “break,” are all seen as being unlucky and are avoided.

▼ Remember: no knives.

The ceremonial eating of kagami mochi actually stems back to Japan’s Heian period, spanning the years 794 to 1185. It started with the imperial ritual of hagatame no gi, or the teeth-hardening ritual. For the people of the Heian era, the more teeth someone had then the healthier they were, leading to longer lives. So, people offered hard foods they believed would strengthen teeth to the emperor, like kagami mochi, with the hope of elongating his life.

Later, in the Sengoku (15th and 16th centuries) and Edo (1603-1868) periods, samurai also had a similar tradition. During the New Year, they offered a mochi similar to kagami mochi to their armor, in a ceremony known as gusoku iwai. Armor and weaponry were seen as the soul of a samurai warrior, so it was done to show veneration.

▼ That helmet definitely looks hungry for mochi to me.

The tradition of using a wooden mallet and the date of kagami biraki comes from the gusoku iwai ceremony. Originally held on January 20, it shifted to January 11 following the shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu’s death. The period of matsu no uchi was similarly impacted. Now, matsu no uchi in the Kanto region ends on January 7, with kagami biraki on January 11. On the other hand, in the Kansai region, both are on January 15.

With mochi being so deeply woven into Japanese history and tradition, it’s no wonder that Japanese people continue to consume it, despite the risks it poses. Nowadays, the traditional way of eating mochi for New Year’s is in a soup called ozoni. There are countless regional variations of the dish, highlighting local ingredients and traditions.

▼ Saitama’s version of ozoni

Regardless of what dish the mochi comes in, it remains a hazard. To prevent accidents you should cut the mochi into small bite-size chunks and drink some liquids before eating to help lubricate your throat. If it does get stuck in someone’s throat:

- Immediately call the emergency number 119.

- Try to make them cough or vomit

- If they can’t cough, tilt their chin and firmly strike their back between the shoulder blades.

Whether you want to enjoy it in the traditional way, or try out a new recipe, remember to eat safely and be mindful of small children and the elderly, who are more likely to suffer from an accident.

Despite its dangers, the enduring presence of mochi at New Year’s is proof of the extent that Japanese people will go to preserve tradition and connections to the past, even if it means risking a hospital visit.

Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, Government Public Relations Online, FNN Prime Online, Saison Life Research, All About, World Folk Song

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: Pakutaso (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), Wikipedia Creative Commons

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Japan’ deadliest New Year’s food may be even more dangerous in 2021 due to the coronavirus

Japan’ deadliest New Year’s food may be even more dangerous in 2021 due to the coronavirus Japan’s most dangerous New Year’s food causes death once again in Tokyo

Japan’s most dangerous New Year’s food causes death once again in Tokyo Mochi continues to be Japan’s deadliest New Year’s food, causes two deaths in Tokyo on January 1

Mochi continues to be Japan’s deadliest New Year’s food, causes two deaths in Tokyo on January 1 Traditional Japanese Food Kills Two People, 15 More Hospitalized

Traditional Japanese Food Kills Two People, 15 More Hospitalized Have you ever noticed how much Totoro looks like New Year’s mochi? This plushie’s designers did, and the result is adorable!

Have you ever noticed how much Totoro looks like New Year’s mochi? This plushie’s designers did, and the result is adorable! Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Japanese restaurant serves meals to diners via a moving steam locomotive train

Japanese restaurant serves meals to diners via a moving steam locomotive train Cherry blossom mochi lattes arrive at Japan’s Pronto cafe chain to start sakura sweets season

Cherry blossom mochi lattes arrive at Japan’s Pronto cafe chain to start sakura sweets season Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Swapping seats on Japan’s bullet trains is not allowed, Shinkansen operator says

Swapping seats on Japan’s bullet trains is not allowed, Shinkansen operator says Ghibli Museum’s rooftop Robot Soldier captivates fans as snow falls in Tokyo【Video】

Ghibli Museum’s rooftop Robot Soldier captivates fans as snow falls in Tokyo【Video】 What’s inside Starbucks Japan’s fukubukuro lucky bag for 2026?

What’s inside Starbucks Japan’s fukubukuro lucky bag for 2026? The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years

Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Disney’s Japanese New Year’s plushies and figures are ready to make oshogatsu cuter than ever

Disney’s Japanese New Year’s plushies and figures are ready to make oshogatsu cuter than ever Deadly New Year mochi strikes again, hospitalizing 19 and resulting in 4 deaths

Deadly New Year mochi strikes again, hospitalizing 19 and resulting in 4 deaths Totoro, Spirited Away tenugui tapestries promise good luck at New Year’s, smiles all the time【Pics】

Totoro, Spirited Away tenugui tapestries promise good luck at New Year’s, smiles all the time【Pics】 Mochi, the danger of Japanese New Year’s, claims another life, rushes many to hospital

Mochi, the danger of Japanese New Year’s, claims another life, rushes many to hospital Spending New Year’s alone? Japanese restaurant has special one-person kosechi New Year’s meals

Spending New Year’s alone? Japanese restaurant has special one-person kosechi New Year’s meals The meaning of the mandarin and 6 other Japanese New Year traditions explained

The meaning of the mandarin and 6 other Japanese New Year traditions explained No need to be lonely at New Year’s with Japan’s new one-person osechi set【Taste test】

No need to be lonely at New Year’s with Japan’s new one-person osechi set【Taste test】 Starbucks Japanese New Year’s Frappuccino: Too delicious to wait for January to drink【Taste test】

Starbucks Japanese New Year’s Frappuccino: Too delicious to wait for January to drink【Taste test】 Japan’s otoshidama tradition of giving kids money at New Year’s gets a social welfare upgrade

Japan’s otoshidama tradition of giving kids money at New Year’s gets a social welfare upgrade Cha-Ching! Kids in Japan Receive Up to $1,500 During New Year’s

Cha-Ching! Kids in Japan Receive Up to $1,500 During New Year’s Survey says osechi New Year’s food differs according to each region in Japan

Survey says osechi New Year’s food differs according to each region in Japan Six things to avoid doing in the first three days of the Japanese New Year to have the best luck

Six things to avoid doing in the first three days of the Japanese New Year to have the best luck More people in Japan quit sending New Year’s cards and many have started to regret it

More people in Japan quit sending New Year’s cards and many have started to regret it Workers’ mental health more important than 2 million yen as ramen chain closes for New Year’s

Workers’ mental health more important than 2 million yen as ramen chain closes for New Year’s Learn how to do Japanese New Year’s the right way and avoid bad luck

Learn how to do Japanese New Year’s the right way and avoid bad luck Supporting anime/idol crush tops Japanese teen girls’ New Year’s cash spending targets【Survey】

Supporting anime/idol crush tops Japanese teen girls’ New Year’s cash spending targets【Survey】