When you really think about them, even the traditions and practices that we each grew up with and seem perfectly normal are kind of odd. Easter, once solely the Christian celebration of the resurrection of Jesus, now sees us telling children that a benevolent rabbit came in the night to leave them chocolate eggs. Christmas takes us even further into the world of fantasy as kids grow up thinking that a magical man who lives in the North Pole works a team of elves all year round to make presents for them, delivering said gifts across the world in a single night via flying woodland beasts, despite the man himself likely having respiratory problems owing to his XXL frame.

Although Japan doesn’t really do Christmas, it does have a plenty of its own traditions and yearly celebrations, and it just so happens that today is one of them. Setsubun, or the spring bean-throwing festival, sees children yelling at and peppering fictional demons with handfuls of roasted beans, and families sitting down to eat enormous pieces of maki, or roll, sushi, often adhering to peculiar local traditions as they do.

Setsubun (written 節分) is the day on which Japanese people traditionally welcome in a fresh new year following the cold winter. It may still be incredibly chilly in most of Japan, but every February 3, families force the “demons” out of their home and wish for good luck as spring approaches.

Traditionally, the eldest male member of the household will throw a handful of roasted soybeans, called fuku mame, (meaning “lucky beans”) out of the front door of the house, as if to symbolise chasing away a demon, or oni. Whenever there are children in the house, however, more often than not someone – usually poor old Dad – has to don an oni mask and dance around menacingly while the kids throw the beans at him and shout 鬼は外!福は内! (Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi), meaning “Demons out! Good luck in!”

▼ It’s not easy being an oni!

Image: Harbord Japanese Culture Club

Of course, some little people take the business of driving out demons more seriously than others. One Twitter user in Japan, for instance, yesterday commented that they returned home to find their young daughter “training” for today’s bean throwing, using a makeshift demon for target practice.

▼ Give those demons hell, kid!

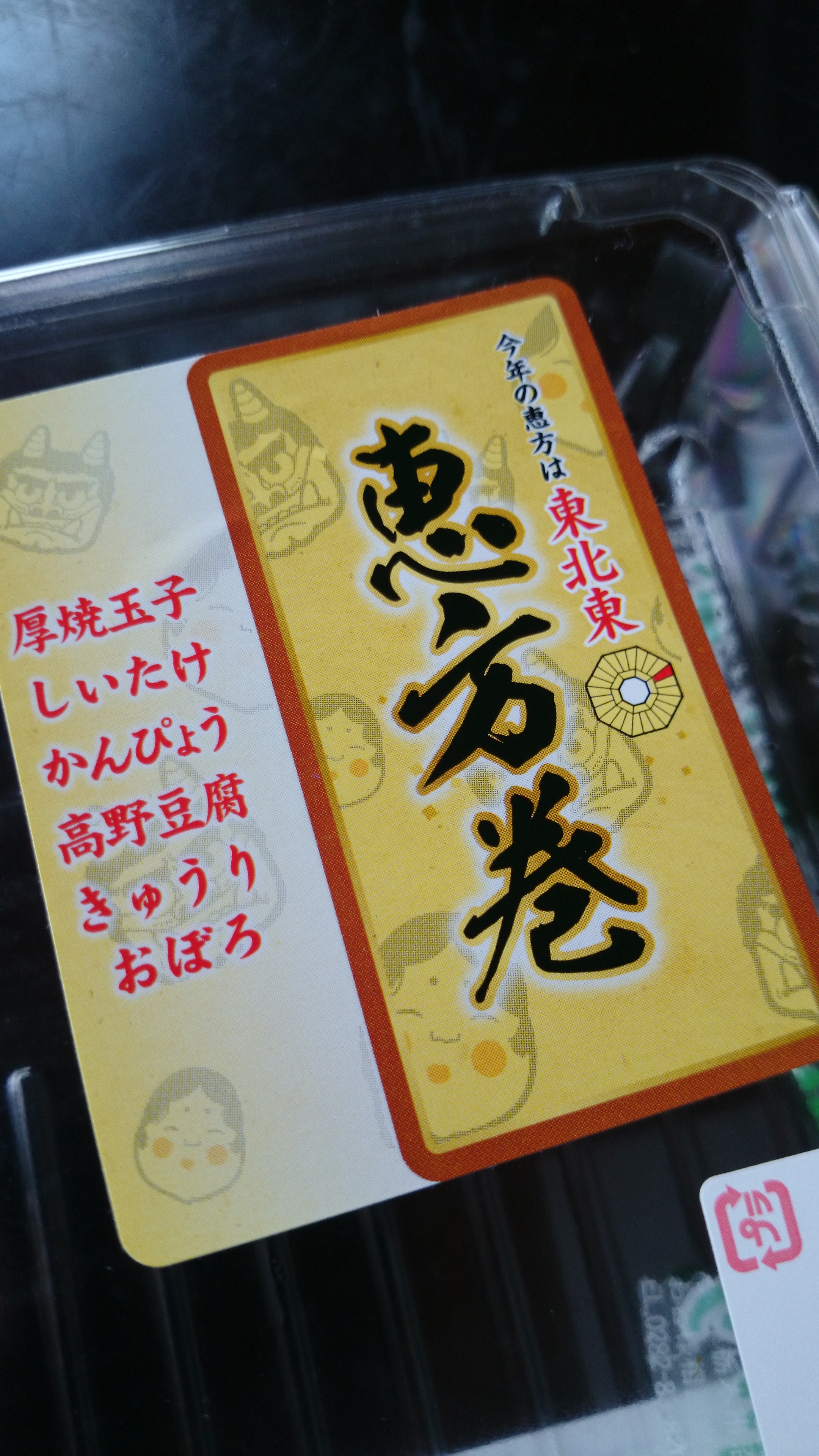

With the throwing finished, it’s time to get down to the bit that even the adults in the house usually look forward to: eating. Ehoumaki, written 恵方巻き (lit. blessing, way/direction, roll), are huge sushi rolls that traditionally contain seven ingredients (seven being a lucky number), and are thought to originate from Osaka and the greater Kansai region. The rolls were once more commonly known simply as marukaburi zushi, with maru meaning “in one” or “whole”, and kaburi denoting the process of eating in huge great mouthfuls.

In 1998, however, convenience store chain 7-Eleven began selling the sushi rolls across the entire country, branding them ehoumaki. They have been popular even outside of Kansai ever since, with supermarkets and convenience stores selling them by the truckload every setsubun, some of them measuring up to 20cm (8 inches) in length and being twice or three times the thickness of normal makizushi rolls.

Viewed up close, these ehoumaki probably don’t look so enormous, but with an everyday object laid beside them for comparison, it’s easy to see that even these regular, store-bought rolls are absolute monsters and so heavy that they’re almost impossible to pick up with chopsticks.

Bought from a regular supermarket, this particular pair of rolls cost 1,000 yen (US$10), and were stuffed with tamagoyaki, cucumber, denbu (dried, seasoned fish), freeze-dried tofu, shiitake mushroom, kanpyou (dried gourd shavings), and of course rice.

Besides being incredibly tasty and filling, the general idea is that eating these rolls will bring good fortune over the coming year. It also helps that, as big as they are, the rolls almost resemble the kind of poles or clubs one might use to chase a pesky demon out of the family home and end a blight of bad luck.

Depending on the region, or sometimes even individual household, there are additional traditions surrounding the eating of ehoumaki. In some parts of Osaka, for example, people make it a rule to eat their entire sushi roll with their eyes closed. In others, it’s customary to consume it all while smiling. Finally, perhaps created by tired parents who just wanted a few minutes’ peace, some people believe that one should remain silent from the moment they take their first bite of an ehoumaki until they swallow the very last grain of rice.

But whether you’re smiling, eating in the dark, or in total silence, if you want the coming year to be really, really lucky, you should pay close attention to the direction you face while eating your ehoumaki. According to the label on the ehoumaki we had earlier today, this year’s “lucky direction” is “east-north-east”, and should be faced while the eating it.

Sadly, we were too hungry to think about such things and had finished off the entire sushi roll before realising that we were probably facing in the completely wrong direction. Oh well, there’s always next year, right?

Happy Setsubun, everyone!

Photos: RocketNews24

It’s time to throw beans and banish demons! A look at family Setsubun traditions in Japan

It’s time to throw beans and banish demons! A look at family Setsubun traditions in Japan These convenience stores really, really want you to buy their ehomaki Setsubun rolls

These convenience stores really, really want you to buy their ehomaki Setsubun rolls From San-X to Attack on Titan, yummy cake rolls take over Bean-Throwing Festival’s sushi custom

From San-X to Attack on Titan, yummy cake rolls take over Bean-Throwing Festival’s sushi custom Sushiro celebrates a traditional Japanese holiday with this…sushi thing

Sushiro celebrates a traditional Japanese holiday with this…sushi thing Japan’s Setsubun Bean-Throwing Bazooka is so powerful demons won’t dare come near you

Japan’s Setsubun Bean-Throwing Bazooka is so powerful demons won’t dare come near you Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway

Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Japan has a new bar just for people thinking about quitting their jobs, and the drinks are free

Japan has a new bar just for people thinking about quitting their jobs, and the drinks are free Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism”

Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism” Japanese breast size study shows rapid growth in previously smallest-busted region of county

Japanese breast size study shows rapid growth in previously smallest-busted region of county Japanese police officer pursues, pulls over Lamborghini supercar…while on a bicycle【Video】

Japanese police officer pursues, pulls over Lamborghini supercar…while on a bicycle【Video】 What are McDonald’s macarons really like in Japan?

What are McDonald’s macarons really like in Japan? Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth You can now visit a recreation of Evangelion’s Tokyo-3 and live there in miniature form in【Pics】

You can now visit a recreation of Evangelion’s Tokyo-3 and live there in miniature form in【Pics】 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Demon babies spotted in Japanese newborns ward, overpower Internet with their cuteness

Demon babies spotted in Japanese newborns ward, overpower Internet with their cuteness Lucky sushi rolls coming to Kansai Aeon stores again for “Summer Setsubun”

Lucky sushi rolls coming to Kansai Aeon stores again for “Summer Setsubun” Pray for sound health for your beloved pets this Setsubun with special good luck sushi rolls just for them

Pray for sound health for your beloved pets this Setsubun with special good luck sushi rolls just for them Date of Japanese holiday Setsubun changes to 2 February for first time in 124 years

Date of Japanese holiday Setsubun changes to 2 February for first time in 124 years Testing Amazon Japan’s best and worst Japanese demon costumes【Photos】

Testing Amazon Japan’s best and worst Japanese demon costumes【Photos】 Robocop called in to exorcise demons at this year’s Setsubun festival in Tokyo

Robocop called in to exorcise demons at this year’s Setsubun festival in Tokyo Dean & DeLuca now has fancy good luck sushi rolls to help Japan celebrate Setsubun【Photos】

Dean & DeLuca now has fancy good luck sushi rolls to help Japan celebrate Setsubun【Photos】 Red Oni and Blue Oni penguins at Tohoku Safari Park bring good luck and cuteness to guests

Red Oni and Blue Oni penguins at Tohoku Safari Park bring good luck and cuteness to guests The greatest sushi roll in Japanese history is actually nine sushi rolls in one【Photos】

The greatest sushi roll in Japanese history is actually nine sushi rolls in one【Photos】 Want more fish in your sushi roll? Japanese restaurant will give you a Whole Sardine Roll

Want more fish in your sushi roll? Japanese restaurant will give you a Whole Sardine Roll Tokyo to be treated with too many tantalizing ehomaki sushi rolls this Setsubun

Tokyo to be treated with too many tantalizing ehomaki sushi rolls this Setsubun Celebrate the coming of spring by feasting on an enormous, $200 luxury Ehomaki roll!

Celebrate the coming of spring by feasting on an enormous, $200 luxury Ehomaki roll! Everyone in the office works together to make a “Dark Ehomaki Sushi Roll” for Setsubun

Everyone in the office works together to make a “Dark Ehomaki Sushi Roll” for Setsubun American ehomaki? Searching for lucky Setsubun sushi rolls in the U.S.【Taste test】

American ehomaki? Searching for lucky Setsubun sushi rolls in the U.S.【Taste test】 We try Yoshinoya’s take on Setsubun ehomaki lucky sushi rolls with mixed results

We try Yoshinoya’s take on Setsubun ehomaki lucky sushi rolls with mixed results