When Steve Jobs showed up at the San Francisco airport at the age of 19, his parents didn’t recognize him.

Jobs, a Reed College dropout, had just spent a few months in India.

He had gone to meet the region’s contemplative traditions — Hinduism, Buddhism — and the Indian sun had darkened his skin a few shades.

The trip changed him in less obvious ways, too.

Although you couldn’t predict it then, his travels would end up changing the business world.

Back in the Bay Area, Jobs continued to cultivate his meditation practice. He was in the right place at the right time; 1970s San Francisco was where Zen Buddhism first began to flourish on American soil. He met Shunryu Suzuki, author of the groundbreaking “Zen Mind, Beginners Mind,” and sought the teaching of one of Suzuki’s students, Kobun Otogawa.

Jobs met with Otogawa almost every day, Walter Isaacson reported in his biography of Jobs. Every few months, they’d go on a meditation retreat together.

Zen Buddhism, and the practice of meditation it encouraged, were shaping Jobs’ understanding of his own mental processes.

“If you just sit and observe, you will see how restless your mind is,” Jobs told Isaacson. “If you try to calm it, it only makes things worse, but over time it does calm, and when it does, there’s room to hear more subtle things — that’s when your intuition starts to blossom and you start to see things more clearly and be in the present more. Your mind just slows down, and you see a tremendous expanse in the moment. You see so much more than you could see before. It’s a discipline; you have to practice it.”

Jobs felt such resonance with Zen that he considered moving to Japan to deepen his practice. But Otogawa told him he had work to do in California.

Evidently, Otogawa was a pretty insightful guy.

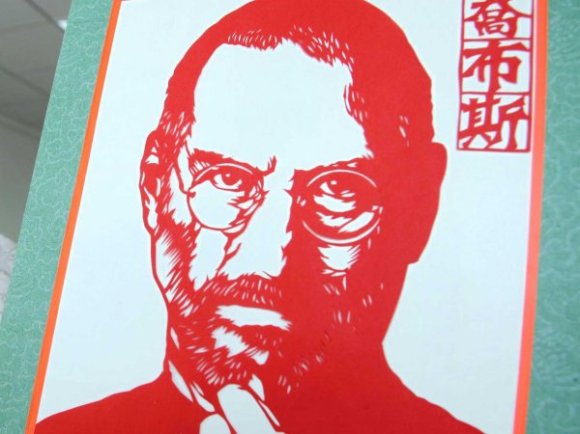

When you look back at Jobs’ career, it’s easy to spot the influence of Zen. For 1300 years, Zen has instilled in its practitioners a commitment to courage, resoluteness, and austerity — as well as rigorous simplicity.

Or, to put it into Apple argot, insane simplicity.

Zen is everywhere in the company’s design.

Take, for instance, the evolution of the signature mouse:

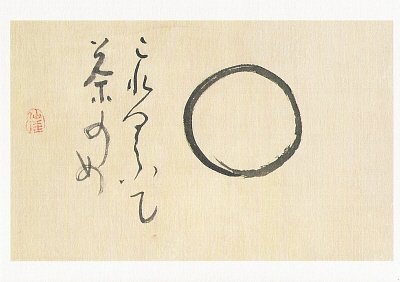

It’s the industrial design equivalent of the enso, or hand-drawn circle, the most fundamental form of Zen visual art.

But Zen didn’t just inform the aesthetic that Jobs had an intense commitment to, it shaped the way he understood his customers. He famously said that his task wasn’t to give people what they said they wanted; it was to give them what they didn’t know they needed.

“Instead of relying on market research, [Jobs] honed his version of empathy — an intimate intuition about the desires of his customers,” Isaacson said.

What’s the quickest way to train your empathy muscles? As centuries of practitioners and an increasingly tall stack of studies suggest, it’s meditation.

When you take that into account, it’s easy to see that for Jobs, growing his business and cultivating his awareness weren’t opposing endeavors.

When he died, the New York Times ran a stirring quote about what he did for society: “You touched an ugly world of technology and made it beautiful.”

We can thank that time in India and on the meditation cushion for that beautiful, rigorous simplicity — one that sparked a design revolution.

Steve Jobs…manga hero???

Steve Jobs…manga hero??? Steve Jobs Much Better at Marketing than Cooking

Steve Jobs Much Better at Marketing than Cooking iMakeover: Can a haircut turn Mr. Sato into Steve Jobs?

iMakeover: Can a haircut turn Mr. Sato into Steve Jobs? Famed educator says Steve Jobs, Bill Gates would have been ruined by Japanese education system

Famed educator says Steve Jobs, Bill Gates would have been ruined by Japanese education system Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Who actually writes Japan’s Letters from Little Sister and schoolgirl love letter capsule toys?

Who actually writes Japan’s Letters from Little Sister and schoolgirl love letter capsule toys? Extreme Budget Travel! Can you do a trip to Manila with 50,000 yen (US$333)? – Part 2

Extreme Budget Travel! Can you do a trip to Manila with 50,000 yen (US$333)? – Part 2 Falafel, beer, and water wheels: Shibuya and Harajuku’s tucked-away treasures 【Hidden Tokyo】

Falafel, beer, and water wheels: Shibuya and Harajuku’s tucked-away treasures 【Hidden Tokyo】 American-Japanese model Kiko designs “morning cleavage” bra for lingerie brand Wacoal 【Video】

American-Japanese model Kiko designs “morning cleavage” bra for lingerie brand Wacoal 【Video】 Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of

Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years

Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says