Stupidly rigid rules dangle down to infuriate older brother.

Between the emphasis Japanese society puts on formal education and the competitive admissions systems which often require students to take grueling entrance exams, there’s an intense pressure on kids in Japan to arrive at the right answers in their classwork. Things get even worse, though, when you add in the baffling requirements some schools have regarding how pupils arrive at them.

Japanese Twitter user @yomos1354 has a younger, elementary school-age brother, who recently brought home his graded math test. In one section, he managed to get all 10 questions wrong, which would ordinarily be pretty troubling, since they were all simple addition problems involving pairs of single-digit numbers.

But then @yomos1354 took a closer look, and realized that it’s not his brother who’s dumb, but his school.

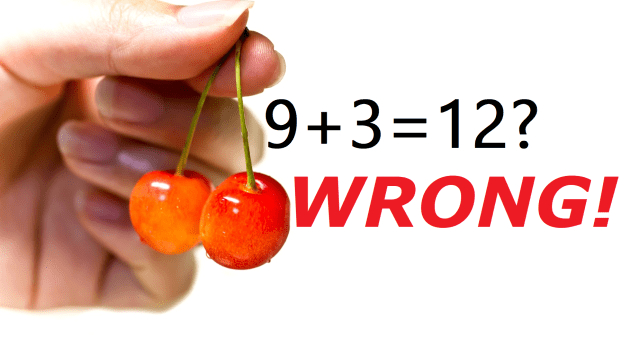

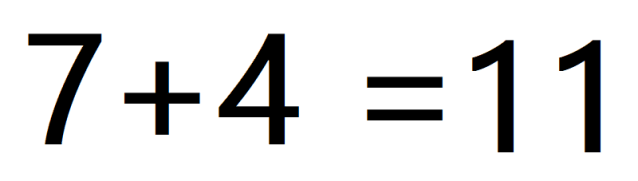

https://twitter.com/yomos1354/status/1061965466325798912Among his brother’s responses that were marked wrong were “9+3=12” and “7+4=11.” Now, it’s true that mathematics-related linguistics often work differently in Japanese and English, but the actual phenomena of addition is universal, so what was the problem?

If you look at the first question on the test, you’ll see a note, written in red, from the boy’s teacher, which reads “sakuranbo keisan,” or “cherry calculation.” Cherry calculation is a method taught in some schools that gets its name from the annotations kids are supposed to make on their paper, which resemble a pair of dangling cherries.

For example, let’s take a look at how the cherry calculation would go for adding 7 and 4.

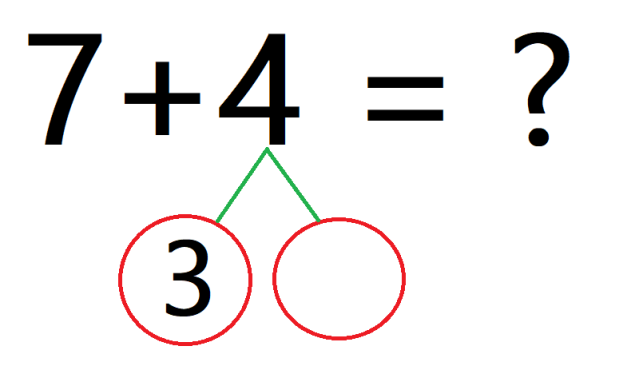

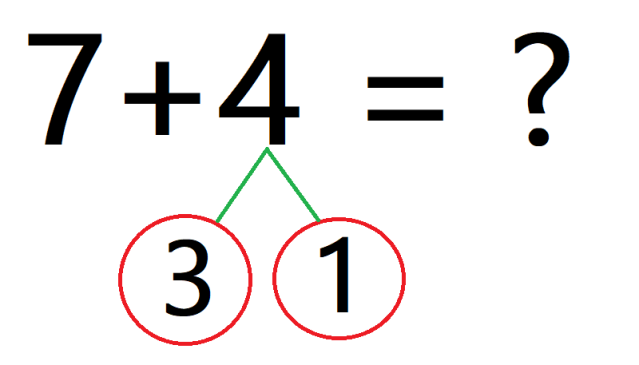

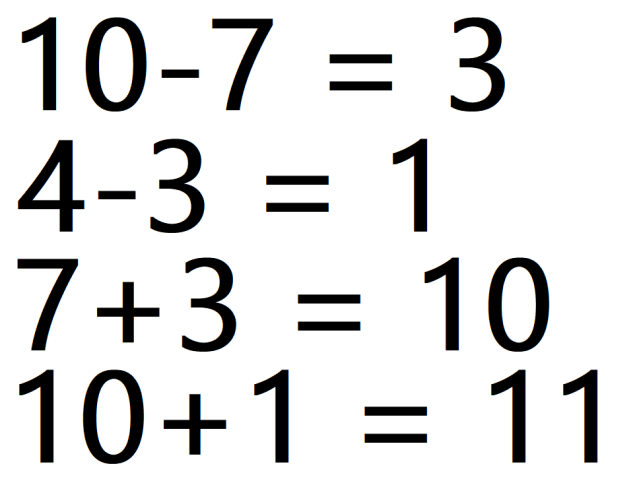

To start, the student is supposed to look at the first number in the problem and ask how much needs to be added to it to get to 10. In this case, we need another 3 to get from 7 to 10, so the next step is for the student to break off 3 from the second number in the problem and write it below.

Then the student subtracts 3 from 4 and writes the difference next to the 3.

Now having filled in both “cherries,” the student completes the calculation by acknowledging that the first number from the original problem plus the first cherry equals 10, and then using the number in the second cherry for the value of the ones-digit, giving the final answer of 11.

In all fairness, it should be recognized that the cherry calculation works. Performed properly, it produces the correct answer. However, there’s no getting around the fact that it replaces a single computation with four, and also requires the problem-solver to mix two types of computations, subtraction and addition.

▼ Standard computation

▼ Cherry computation

More than one online commenter asked if perhaps the class had been instructed to show their work using the cherry calculation method, but @yomos1354 says there’s no such directions written on the test, nor were the students verbally told to do so.

Of course, no one would have gone to the trouble to develop and teach the cherry calculation method if it didn’t have any possible benefits. Proponents say it can be an effective way to help young learners get over mental hurdles about how exactly arithmetic works. If a kid is completely stumped as to how to go about solving the question “7+4=?”, the cherry calculation is a method by which a teacher can give a helping hand without just solving the problem for him. “OK, how many more do we need to add to seven to get to 10?” the teacher might ask. Once the student has taken that step, the next questions would be “And if we take three away from four?” and “And what’s 10 plus 1?” This breaks the question into smaller chunks that might be easier for a child’s mind to grasp if he’s having trouble understanding the concept of how the ones-digit wraps back around to zero each time the tens-digit goes up an integer.

But all that just makes @yomos1354 even more frustrated about how his brother’s test was graded. The cherry calculation is supposed to provide assistance for those students who can’t do the calculations in their head or all in one simple step. His brother is already clearly proficient enough to not need to rely on drawing little cherries under the problems. “Not even funny how he got marked down,” @yomos1354 tweeted. “The school has no business forcing everyone to use the [cherry calculation] method for problems that are this simple,” understandably upset at how forcing his brother to use an educational crutch he doesn’t require would be hobbling him intellectually.

It’s another frustrating example of how students can sometimes get penalized for being ahead of the game in Japan, so hopefully next year @yomos1354’s little bro will be lucky enough to end up in a class taught by one of Japan’s awesomely flexible teachers instead.

Sources: Twitter/@yomos1354 via Jin, Shogakko Nyugaku Joshi no Mama Nikki, Print Kids

Top image: Pakutaso (edited by SoraNews24)

Insert images: SoraNews24

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he wrote this whole article with Ai Otsuka’s “Sakuranbo” stuck in his head.

Japanese elementary school kid says 12 x 25 = 300, teacher doesn’t say he’s answered correctly

Japanese elementary school kid says 12 x 25 = 300, teacher doesn’t say he’s answered correctly Japanese elementary school student teaches us how to solve a difficult maths problem

Japanese elementary school student teaches us how to solve a difficult maths problem How to convert the Western calendar to Japanese Reiwa years

How to convert the Western calendar to Japanese Reiwa years Don’t like trigonometry? Then you’re just like Hitler, says Japanese high school English teacher

Don’t like trigonometry? Then you’re just like Hitler, says Japanese high school English teacher “A dead bug” and other amusing, adorable, snarky, and downright ridiculous test responses

“A dead bug” and other amusing, adorable, snarky, and downright ridiculous test responses Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day

Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it

Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes Starbucks Japan releases new mugs and gifts for Mother’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new mugs and gifts for Mother’s Day French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Ghibli Park now selling “Grilled Frogs” from food cart in Valley of Witches

Ghibli Park now selling “Grilled Frogs” from food cart in Valley of Witches Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】

Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】 Japan’s massive matcha parfait weighs 6 kilos, contains hidden surprises for anyone who eats it

Japan’s massive matcha parfait weighs 6 kilos, contains hidden surprises for anyone who eats it Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles

Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Students go nearly a year without textbooks after teacher forgets to hand them out

Students go nearly a year without textbooks after teacher forgets to hand them out Chiba teacher arrested for threats to “blow up government buildings” because of Saturday classes

Chiba teacher arrested for threats to “blow up government buildings” because of Saturday classes Petition to allow students to choose what they wear to school gathers almost 19,000 signatures

Petition to allow students to choose what they wear to school gathers almost 19,000 signatures Japanese schools are losing their pools due to rising maintenance costs and aging facilities

Japanese schools are losing their pools due to rising maintenance costs and aging facilities Japanese first grader wins math contest by quantifying “which hiragana are the hardest to write”

Japanese first grader wins math contest by quantifying “which hiragana are the hardest to write” Uncle and netizens confused about child’s low grade on math assignment

Uncle and netizens confused about child’s low grade on math assignment Is Japan overworking its teachers? One exhausted educator says, “YES!”

Is Japan overworking its teachers? One exhausted educator says, “YES!” Knife-wielding professor fired from international department of one of Tokyo’s top universities

Knife-wielding professor fired from international department of one of Tokyo’s top universities Your iPhone is embarrassingly bad at simple math

Your iPhone is embarrassingly bad at simple math Famed educator says Steve Jobs, Bill Gates would have been ruined by Japanese education system

Famed educator says Steve Jobs, Bill Gates would have been ruined by Japanese education system Japanese high school teacher in hot water after forcibly giving male student a buzz cut

Japanese high school teacher in hot water after forcibly giving male student a buzz cut When bullying happens in Japan, should parents go to the police? We ask an educator

When bullying happens in Japan, should parents go to the police? We ask an educator “Hate summer homework, kids? We’ll do it for you!” A disturbingly booming business in Japan

“Hate summer homework, kids? We’ll do it for you!” A disturbingly booming business in Japan Under 35 percent of middle school English teachers in Japan meet government proficiency benchmark

Under 35 percent of middle school English teachers in Japan meet government proficiency benchmark

Leave a Reply