Sweets we bought on the street turn out to be suspiciously delicious.

After finishing work the other day, our Japanese-language reporter Yuichiro Wasai was walking to the station to catch a train home when a young woman called out to him. He’d never seen her before, and for a second he almost thought she might be about to ask him out on a date.

It quickly became apparent, though, that the woman didn’t speak much Japanese at all. Instead, she pointed towards the sign she was holding, on which she’d written, in Japanese:

“I’m having trouble making ends meet during the coronavirus pandemic. Please buy my homemade chocolate.”

Speaking in broken Japanese, the woman said she was a foreign student currently going to school in Japan, and this set off some warning bells in Yuichiro’s head. Since the start of the pandemic, there’s been an increase in non-Japanese people selling various trinkets on the street, usually with some sort of story about how they’re in Japan on a student visa but no longer able to support themselves. Their stories are often vague and lack specific details, though, and it’s hard to get answers to any further questions, as the sellers often say they don’t speak Japanese well enough to understand the query or convey the answer. In other words, it’s hard to tell if they’re legitimate students going through a rough patch, or just scam artists looking to profit off kindhearted people’s sympathy.

When Yuichiro asked if he could take a picture of the woman’s sign, the woman said no, he couldn’t, which didn’t exactly inspire confidence. “What if she’s lying?” Yuichiro thought. “Maybe this is part of some scam operation and I’ll be funding a bunch of fraudsters?” But then the little compassionate angle aspect of Yuichiro’s psyche settled on his shoulder, and in his stomach. “Maybe she’s telling the truth, and anyways, you know you like chocolate, dude. She’s asking 500 yen [US$4.80] a bag, and if she honestly is hard up for cash, you’d be helping her out.”

There’s another wrinkle to the debate, which is that unlicensed selling of goods on the street like this is technically illegal. In the end, though, Yuichiro decided to buy some of the woman’s chocolate, and actually ended up getting two bags, since he didn’t have any coins on him and didn’t want to look like a cheapskate buy asking a starving student for change for a 1,000-yen bill.

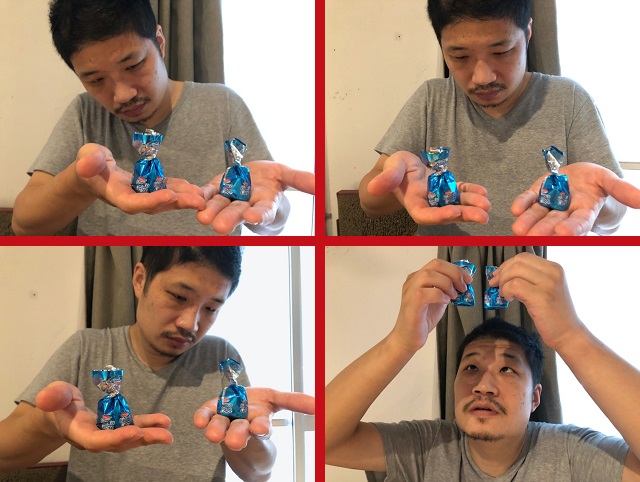

Once he got back home Yuichiro took a look at what he’d bought, and yeah, the bag definitely had a cute, do-it-yourself vibe to it, totally in keeping with someone who’d whipped up a batch of chocolates in their kitchen.

The bags were clear on their backside, and flipping them over he could see each morsel was individually wrapped. There was even a best-by date sticker on them, and this indication of care towards his gastronomic health was a nice, reassuring touch.

Yuichiro had actually never eaten a woman’s homemade chocolate before, and he was curious to see what the pieces looked like. Unwrapping one, he found its outer rustically bumpy.

Now it was time for a taste. He was still a little worried, though, and so he kept a paper towel handy to spit the chocolate out into if it tasted suspicious. He then took a deep breath, followed by a bite, and…

…it was delicious! Creamy and sweet, the flavor quickly convinced him that the woman must be a confident chef, and he nodded in understanding of why someone with her talents would think to make money with her culinary skills if she were in a financial pinch. The chocolate was so good that Yuichiro quickly reached for another piece, and before he knew it he’d finished off an entire bag.

But while his stomach was now filled with chocolate, something else was stuck in his mind. Remember how each piece of chocolate was individually wrapped? Something about the graphic design looked just a little too polished. He also was curious about the message written on the wrappers: “bianco cuore.”

Granted, a bit of European-language text on Japanese packaging isn’t anything new, but something about this seemed significant. So he Googled the phrase, and learned that there’s a brand of candy with the exact same name that you can buy online from Rakuten, and also at Costco branches in Japan.

But hey, maybe that’s just a coincidence, right? The only way to be sure would be to order some, so that’s exactly what Yuichiro did.

After a few days, his Rakuten shipment came, and he opened up the box to inspect them side-by-side with his remaining bag of “homemade” chocolate, starting with the individual wrappers.

▼ Left: “homemade” chocolate

Right: Rakuten chocolate

Next, he unwrapped one piece of each (again, “homemade” on the left, Rakutan on the right).

And last, he took a bite of each.

Conclusion? They’re exactly the same, and since Bianco Cuore, according to the package of the bag he got from Rakuten, is made in Italy, there’s no chance at all that the chocolate Yuichiro bought from the woman was made in her kitchen.

Still, bighearted guy that he is, Yuichiro still wants to give the woman the benefit of the doubt. “Maybe she didn’t understand that the word she wrote on her sign tezukuri, means ‘homemade,’ and just thought it means ‘delicious?’” he theorizes. “Japanese is a tough language to learn, after all.”

Speaking from the perspective of someone who studied Japanese as a second language, though, that excuse would be hard to swallow. Tezukuri comes from the words te (“hand”) and tsukuru (“make”), i.e. something you made/cooked with your own hands, and since practically every foreigner learns te and tsukuru before they learn tezukuri, it’s pretty easy to grasp that it means “homemade” in regards to food.

Speaking of linguistics, in Japanese the word amai means both “sweet-tasting” and “gullible.” We’ve got a hunch both definitions apply to Yuichiro’s experience, but hey, it’s hard to be too upset when life gives you an excuse to buy three bags of chocolate.

Images ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

A daddy/daughter test of the free baby meals at Japan’s biggest soup restaurant chain【Taste test】

A daddy/daughter test of the free baby meals at Japan’s biggest soup restaurant chain【Taste test】 Try our crappy lifehack for “better BMs”

Try our crappy lifehack for “better BMs” We try cooling our face masks five different ways, and don’t recommend doing any of them

We try cooling our face masks five different ways, and don’t recommend doing any of them We lost the Starbucks lucky bag lotto, so we went on a luxury Starbucks shopping spree instead

We lost the Starbucks lucky bag lotto, so we went on a luxury Starbucks shopping spree instead We ask for an “omakase” selection from Starbucks’ Tokyo bakery Princi, with surprising results

We ask for an “omakase” selection from Starbucks’ Tokyo bakery Princi, with surprising results Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Japanese-style accommodation at the new Premium Dormy Inn hotel in Asakusa will blow your mind

Japanese-style accommodation at the new Premium Dormy Inn hotel in Asakusa will blow your mind Mikado Coffee is a 76-year-old coffee chain with a major celebrity connection

Mikado Coffee is a 76-year-old coffee chain with a major celebrity connection W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most offensive Japanese swear words 【Weird Top Five】

W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most offensive Japanese swear words 【Weird Top Five】 The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there

The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there Same character, different animator – Fans compile comparison charts for anime’s biggest stars

Same character, different animator – Fans compile comparison charts for anime’s biggest stars Fried sandwiches arrive in Tokyo, become hot topic on social media

Fried sandwiches arrive in Tokyo, become hot topic on social media We tried Korea’s way-too-big King Tonkatsu Burger at Lotteria 【Taste Test】

We tried Korea’s way-too-big King Tonkatsu Burger at Lotteria 【Taste Test】 5 cultural tips for taking photos in Japan

5 cultural tips for taking photos in Japan Now you can be one step closer to the very best with your very own life-size, realistic Poké Ball

Now you can be one step closer to the very best with your very own life-size, realistic Poké Ball McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day

Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 Secret Kitchen bento serves Japanese flowers, birds, wind and moon in a box, but is it worth it?

Secret Kitchen bento serves Japanese flowers, birds, wind and moon in a box, but is it worth it? New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint We’re utterly stumped by this kids’ Spot the Difference Puzzle from a Japanese family restaurant

We’re utterly stumped by this kids’ Spot the Difference Puzzle from a Japanese family restaurant We visit Tokyo’s new all-plant-based cafe “Komeda Is □”

We visit Tokyo’s new all-plant-based cafe “Komeda Is □” We went to a Japanese restaurant in Italy, ate green sushi, learned a lesson about taking it easy

We went to a Japanese restaurant in Italy, ate green sushi, learned a lesson about taking it easy Our reporter investigates the strangely named “shaved ice donburi” at a Tokyo cafe

Our reporter investigates the strangely named “shaved ice donburi” at a Tokyo cafe We tried Mama’s Poop served fresh from a Tokyo eatery

We tried Mama’s Poop served fresh from a Tokyo eatery 9 middle-aged Japanese men come to work in the clothes they’d like their partners to wear

9 middle-aged Japanese men come to work in the clothes they’d like their partners to wear We get more than we bargained for with this Akihabara lucky bag

We get more than we bargained for with this Akihabara lucky bag Tokyo Sushi for US 8 cents a piece (as long as you also want a beer) makes us believe in miracles

Tokyo Sushi for US 8 cents a piece (as long as you also want a beer) makes us believe in miracles We spend Culture Day in prison, food was arguably better than Yoshinoya

We spend Culture Day in prison, food was arguably better than Yoshinoya Tokyo restaurant’s crazy huge rice omelet has 600 grams (1.3 pounds) of rice

Tokyo restaurant’s crazy huge rice omelet has 600 grams (1.3 pounds) of rice Cheap vs. expensive — Is a premium-priced tempura bento really worth it?【Taste test】

Cheap vs. expensive — Is a premium-priced tempura bento really worth it?【Taste test】 Can humans eat Japan’s premium cat food Nekkokan? It’s complicated…【Experiment】

Can humans eat Japan’s premium cat food Nekkokan? It’s complicated…【Experiment】 A story of how Starbucks Reserve Roastery products always make us forget about money management

A story of how Starbucks Reserve Roastery products always make us forget about money management We miss out on cheap all-you-can-eat takoyaki, but stuff ourselves with octopus balls anyway

We miss out on cheap all-you-can-eat takoyaki, but stuff ourselves with octopus balls anyway How much will three packs of Pokémon cards bought overseas fetch in Japan?

How much will three packs of Pokémon cards bought overseas fetch in Japan? What happens when our reporters show up to work dressed like their fathers?

What happens when our reporters show up to work dressed like their fathers?

Leave a Reply