We spend a day on the farm learning how much work goes into a single cup of tea.

Most people who grew up in Japan drink a lot of green tea, and our reporter P.K. Sanjun is no exception. But also like a lot of people who grew up here, P.K. has never made green tea from scratch.

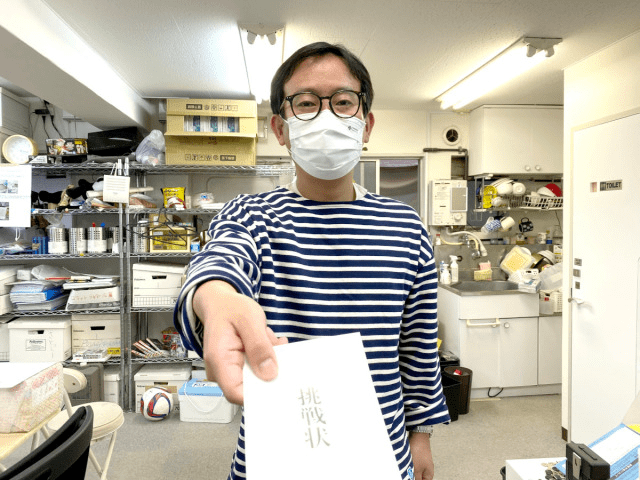

Every single supermarket and convenience store in Japan, and just about every vending machine too, is stocked with bottles of pre-made green tea. You’ll find an assortment of tea bags in the cupboard of most homes and offices, and some aficionados buy canisters of loose leaf tea, but even in those cases, the leaves have already been processed and packaged. Starting out in the fields, though, picking the tea leaves with your own hands and turning them into a cup of tea? That’s a rare experience, and one that the opportunity for came to P.K. by way of our boss, SoraNews24 founder Yoshio.

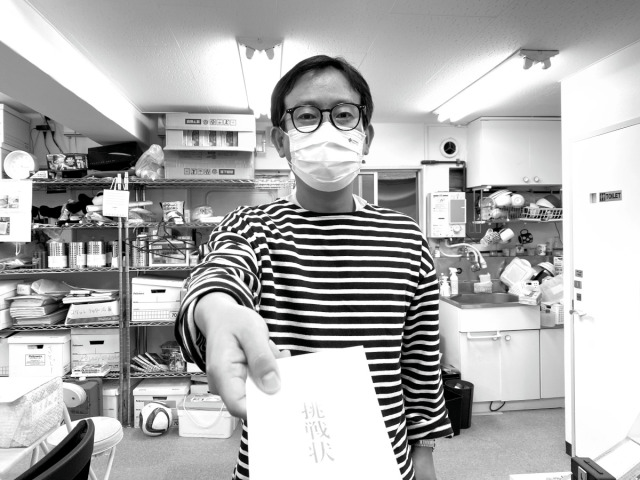

“We received a letter from Itoen,” Yoshio explained, invoking the name of one of Japan’s biggest tea makers, and the company behind the popular Oi Oicha brand of green tea. “They’re inviting you to come make tea with freshly picked leaves. Their representative, Katsuno-san, will meet you at the farm.”

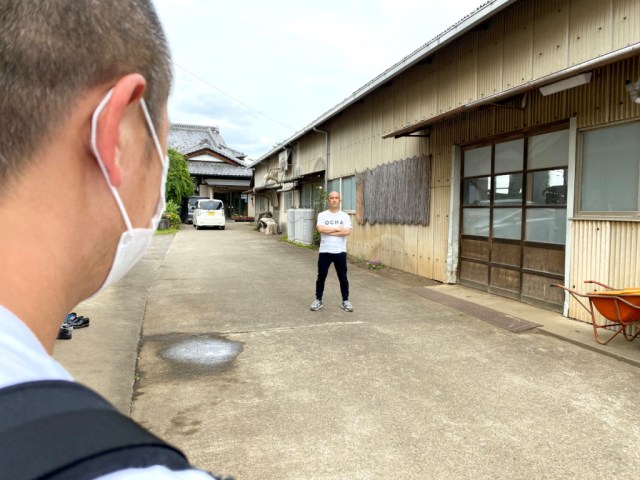

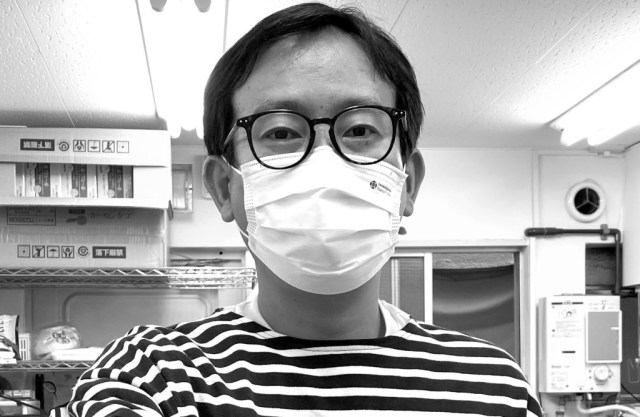

And with that, P.K. was off to the town of Sayama, in Saitama Prefecture. As he walked up to the farm’s office facility to meet with Katsuno, he imagined that anyone working for a tea maker would have an aura as refined and gentle as a perfectly brewed cup of tea. Drawing close to the entrance, he spotted a solitary figure out front waiting for him, and called out “Katsuno-san! Hello, Katsuno-san! It’s me, P.K. Sanjun from SoraNews24!”

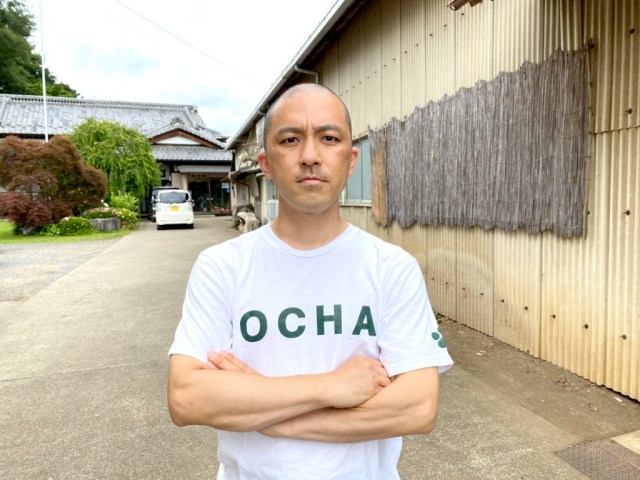

However, Katsuno replied to this greeting with a stern expression.

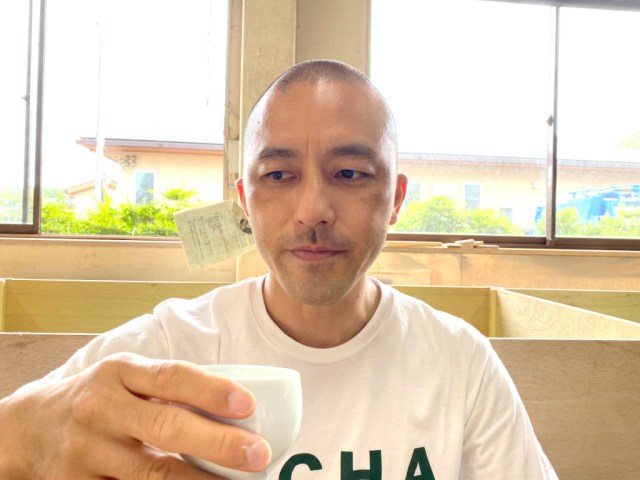

▼ He remained completely silent, with his shirt’s “ocha” (the Japanese word for “tea”) saying more than the man himself.

“So, uh, should we get started, Katsuno-san?” P.K. asked, to which Katsuno nodded and began walking with him towards the field. The Sayama site is one of many tea farms Itoen manages across Japan, helping to keep distribution routes short and its products fresh.

One of the farmers explained to P.K. how to pick the leaves, stressing that the key was to remove them carefully one at a time in order to prevent unnecessary tearing or bruising. This was P.K.’s first time to pick tea, and he was impressed by their soft, pliable texture in the palm of his hands, where they had a seemingly palpable freshness. Unaccustomed to field work, though, it wasn’t long before his lower back started to ache. Still, he felt quite proud of himself for filling up both hands with leaves, expecting it to be enough to make several pots’ worth of tea.

▼ Something about it made his paternal instincts kick in and he started thinking of them as his precious tea leaf children.

This, however, was the first of several times P.K. realized he had a lot to learn. “That’s probably enough to brew one cup,” explained his farmer mentor. “Compared to the weight of the raw leaves, you end up with only about one-fifth of that after they’re processed and ready to brew.”

So it was back to harvesting, with P.K. feeling a renewed sense of gratitude for the hard work of Japan’s tea farmers.

Eventually, Katsuno nodded that P.K. had picked enough. Since tea leaves begin to oxidize in the open air shortly after picking, they need to be processed right away before their flavor diminishes, and so Katsuno led P.K. inside for the next step from tea field to teacup.

Inside the processing room were a hot plate and a microwave oven. “Is this really all the equipment I need, Katsuno-san?” P.K. asked, to which he nodded again, said “Brew the tea,” and left P.K. to figure out what to do next on his own.

P.K. knew that you have to remove the moisture from the tea leaves before steeping them, so he started with the hot plate. Figuring that singeing them would make them taste bad, he used a low heat setting. A pleasant tea aroma began to rise from the plate as the leaves warmed, but he noticed that they weren’t really drying very much, so he decided to pop the leaves in the microwave for three minutes instead.

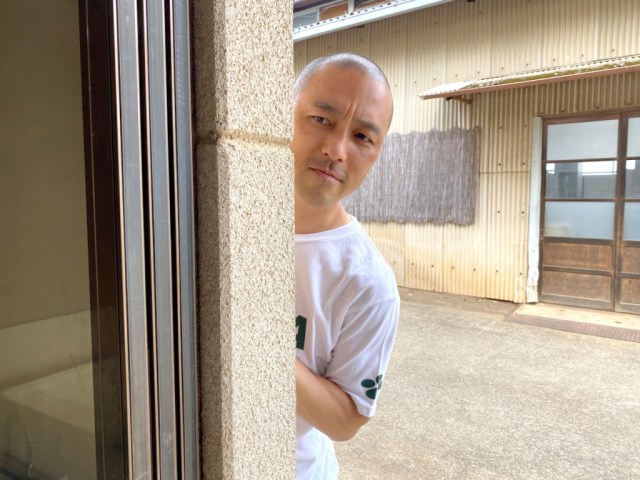

All the while, Katsuno was watching with a stony expression.

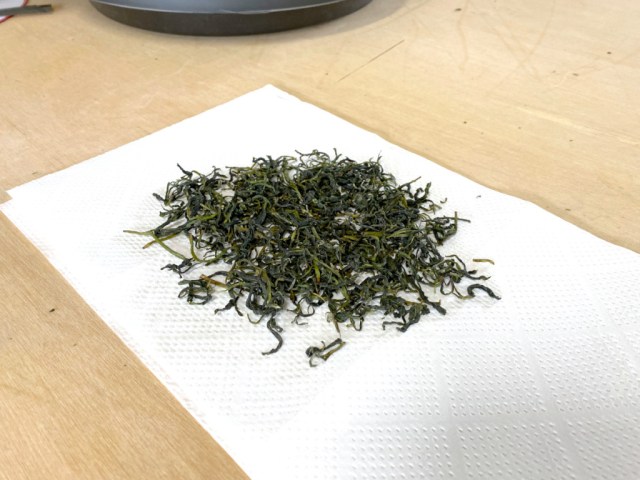

When P.K. took the leaves out of the microwave, they were nice and dry. Next, he grabbed a mortar and gently crushed the leaves into smaller pieces, and his original P.K.-style tea was ready for brewing!

And how did it taste?

Bad. Really, really, bad. It smelled nice enough, but the flavor was mercilessly bitter, so harsh that it was barely drinkable.

P.K.’s shoulders slumped in disappointment, and also guilt at the ignoble fate of his tea leaf babies. It was at this point that Katsuno came in with a batch of tea leaves that he had prepared.

With a gracefulness in stark contrast to his gruff expression, Katsuno paced the leaves in a teapot, steeped them, and poured P.K. a cup.

This was how tea should be.

The tea tasted fresh and smooth, with just the right balance of bracing astringency and comforting sweetness characteristic of Japanese green tea. P.K. was startled that Katsuno’s tea, which came from leaves picked in the same field as P.K.’s, could taste so different from his own sub-par batch. Katsuno’s tea was so good that P.K. believed it could put a smile on anyone’s face…

…even Katsuno’s!

“So what made the difference, Katsuno-san?” asked P.K. It was all the in the way the leaves were treated post-picking, he explained. Katsuno started with the microwave, wrapped the tea leaves in plastic to essentially steam them, and heated them for just one minute instead of three, since over-heating them will produce excess bitterness.

Next, the leaves should be laid out flat on paper towels and cooled with a paper hand fan, much like you’d cool yourself off with on a hot afternoon, to help remove more moisture. Then it’s time to put them on the hot plate, set at low heat.

You don’t want to leave the leaves on the hot plate too long, though. After they’ve warmed, Katsuno says to put them back on paper towels and gently knead them, a process called chamomi, or “tea massaging,” in Japanese. This helps draw out their full flavor and aroma, and you should cycle through the hot plate heating and tea massaging about 10 times. Once that’s done, leave the leaves out to dry for 10 more minutes, and only then are they ready to be steeped, ideally in hot water that’s 80 degrees Celsius (176 degree Fahrenheit).

P.K. was amazed, not just because of how much effort goes into making a truly good cup of tea, but also because of how talkative the previously taciturn Katsuno had become. “Was there something that was upsetting you before, Katsuno-san?” asked P.K., thinking that maybe his lack of prior knowledge of tea production had offended the Itoen representative.

“Well, actually I just thought it was weird that you kept calling me Katsuno, since my name is Kakuno,” he revealed.

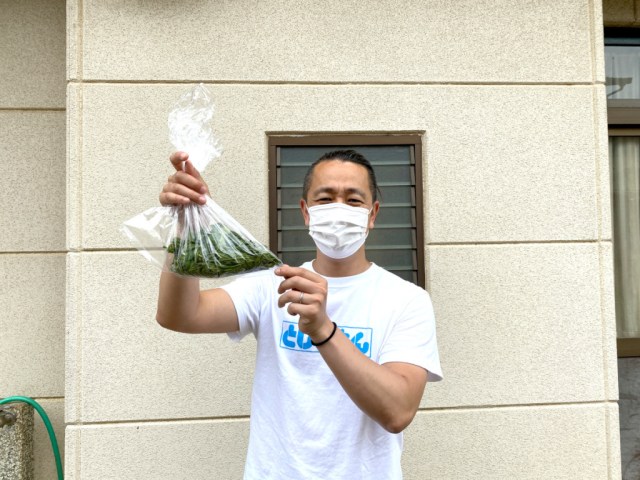

P.K. gulped with embarrassment at his faux pas. “I’m very sorry about that,” he said, and Kakuno seemed to forgive him. He even gave P.K. a bag of freshly picked tea leaves to take home, and explained that right now Itoen is running a promotion where if you follow their official Twitter account, retweet the tweet below, and fill out the form here, you’ll be entered into a drawing to win a bag of your own.

お〜い❗️

— お〜いお茶くん【公式】 (@oiochakun) June 21, 2021

摘みたての生の葉からお茶を作る「鮮度体験キット」を24名の #茶レンジャー へお届けします📣🍃

▼応募方法▼

1⃣@oiochakunをフォロー

2⃣この投稿をRT

3⃣応募フォームに入力https://t.co/5MF6xxKWOW

⌛️締切:7/4 23:59#茶畑エクスプレス #とどけお茶のチカラ pic.twitter.com/GXXX1LYo0U

Still, P.K. felt kind of guilty about the name screw-up for his entire trip back home, until he remembered…

…the exact words our boss had told him:

“Their representative, Katsuno-san, will meet you at the farm.”

“Their representative, Katsuno-san, will meet you at the farm.”

So on this day, P.K. learned two things. One: every time you drink a good cup of tea, there’s a lot of work that went into it. And two: when Yoshio gives you a work assignment, you’ll probably want to double-check the details.

Source: Itoen tea leaf campaign site

Photos ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Drink Green! We check out the amazing “Green Tea Party” presented by Isetan and Ito En! 【Pics】

Drink Green! We check out the amazing “Green Tea Party” presented by Isetan and Ito En! 【Pics】 Sharp’s Ocha-presso brings traditional Japanese flavor to your kitchen

Sharp’s Ocha-presso brings traditional Japanese flavor to your kitchen Häagen-Dazs Japan’s Yuzu Green Tea Float — How to make the super-easy matcha summer dessert drink

Häagen-Dazs Japan’s Yuzu Green Tea Float — How to make the super-easy matcha summer dessert drink Shizuoka Prefecture may lose title of Japan’s top tea producer to rising star Kagoshima

Shizuoka Prefecture may lose title of Japan’s top tea producer to rising star Kagoshima We spill the tea–a guide to all of Japan’s Gogo no Kocha Milk Teas sold in the wintertime

We spill the tea–a guide to all of Japan’s Gogo no Kocha Milk Teas sold in the wintertime Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day

Japanese city loses residents’ personal data, which was on paper being transported on a windy day Ghibli Park now selling “Grilled Frogs” from food cart in Valley of Witches

Ghibli Park now selling “Grilled Frogs” from food cart in Valley of Witches Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it

Harajuku Station’s beautiful old wooden building is set to return, with a new complex around it Historical figures get manga makeovers from artists of Spy x Family, My Hero Academia and more

Historical figures get manga makeovers from artists of Spy x Family, My Hero Academia and more Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it Suntory x Super Mario collaboration creates a clever way to transform into Mario【Videos】

Suntory x Super Mario collaboration creates a clever way to transform into Mario【Videos】 Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates

Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates Japan’s massive matcha parfait weighs 6 kilos, contains hidden surprises for anyone who eats it

Japan’s massive matcha parfait weighs 6 kilos, contains hidden surprises for anyone who eats it Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Stylish green tea “chablets” from Shizuoka are our new way favorite way to grab a cuppa

Stylish green tea “chablets” from Shizuoka are our new way favorite way to grab a cuppa Still using water to make your instant noodles? You’re missing out on amazing green tea noodles!

Still using water to make your instant noodles? You’re missing out on amazing green tea noodles! Sriracha vending machines rising in Japan, our reporter tries it for first time (with Cup Noodle)

Sriracha vending machines rising in Japan, our reporter tries it for first time (with Cup Noodle) How to turn leftover tempura into fried rice (or why to buy all the takeout tempura you can)

How to turn leftover tempura into fried rice (or why to buy all the takeout tempura you can) Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things The twin joys and dual sadnesses of eating ramen in the U.S.

The twin joys and dual sadnesses of eating ramen in the U.S. We ordered the biggest steak we could buy with 10,000 yen at steakhouse chain Ikinari Steak

We ordered the biggest steak we could buy with 10,000 yen at steakhouse chain Ikinari Steak Daily Yamazaki convenience store’s “Flying in the Sky Donuts” are competition for Mister Donut

Daily Yamazaki convenience store’s “Flying in the Sky Donuts” are competition for Mister Donut The time P.K. flatly refused a request from his deceased best friend’s mom at their first meeting

The time P.K. flatly refused a request from his deceased best friend’s mom at their first meeting Suntory explains the simple science behind how it makes its amazing clear tea beverages【Video】

Suntory explains the simple science behind how it makes its amazing clear tea beverages【Video】 Mister Donut demonstrates the wonders of hot bubble tea with royal milk and rich matcha flavors

Mister Donut demonstrates the wonders of hot bubble tea with royal milk and rich matcha flavors Newest Gundam anime robot model kit is made with green tea leaves, smells like green tea

Newest Gundam anime robot model kit is made with green tea leaves, smells like green tea We attempt to buy Starbucks Japan’s 60,000 yen lucky beckoning cat

We attempt to buy Starbucks Japan’s 60,000 yen lucky beckoning cat Kyoto matcha green tea popcorn, the latest must-eat snack from…Frito-Lay?!?

Kyoto matcha green tea popcorn, the latest must-eat snack from…Frito-Lay?!? Five things you should eat at Muji Japan, according to staff who work there

Five things you should eat at Muji Japan, according to staff who work there We ate all eight kinds of cold noodles from 7-Eleven and here’s our favourites【Taste test】

We ate all eight kinds of cold noodles from 7-Eleven and here’s our favourites【Taste test】

Leave a Reply