Innocent idea doesn’t go anywhere close to how she expected.

When choosing a design for a tattoo, most people want something that’s not just cool or beautiful, but meaningful as well. And since you’re going to have the thing forever, an aesthetic that’s already stood the test of time is preferable to some trendy symbol that might feel played out in a few months’ time.

Put all those criteria together, and there’s definitely a certain logic to people choosing Japanese kanji characters for their tattoos, even if they themselves don’t speak the language. However, there’s a danger to having people put words on your body without a sufficient background in the language, since what they actually mean might not match up with the message you’re trying to send.

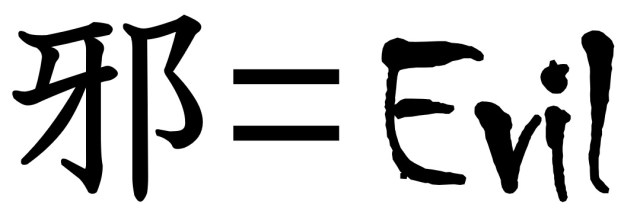

For example, Japanese Twitter user @ToraiKun spent part of his student days studying at a university in the U.S. One day a Caucasian classmate was showing him her kanji tattoo, and @ToraiKun was startled to see that the character she’d chosen was this.

Apparently she wanted to double-check that it meant what she thought it did, so she asked @ToraiKun if he could translate it for her, and he easily could, because it’s a pretty simple translation. It means “evil.”

Now, that tattoo might make sense if @ToraiKun’s classmate had been going through a goth phase or experimenting with other forms of edgy self-impression. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case, and she’d had innocent intentions…literally. “They told me it meant ‘innocent!’” the crestfallen woman said.

前にもツイートしたけど、大学生の時にクラスの白人女性から「邪」と書かれたタトゥを見せられた。意味を聞かれ「"Evil"だ」と答えたら彼女の顔が険しくなり「"Innocent"って言われたのよ!3つあって一番Coolな字を選んだの!」と返された。察した僕は「無邪気」の3文字を教えた。タトゥは危険だね。

— とらい (@ToraiKun) October 9, 2021

Evil, being the active form of malice, is pretty much on the opposite end of the spectrum from innocence, so how did the woman’s tattoo end up being so far off the mark? “There were three characters, and I picked the coolest-looking one,” she explained, and that’s when it clicked that what she’d really wanted was this.

Pronounced mujaki, those three characters do mean “innocent” or “innocence” (the borderline between adjectives and nouns is sometimes a little hazy in Japanese). It sounds like the woman came across them in a booklet of sample tattoo designs, or maybe ran an English-to-Japanese Google search for “innocent,” and saw them explained like this.

Apparently the woman thought all three of those kanji meant “innocent” and picked out the one she liked the best. Here’s the problem, though: “Innocent” is what those three characters mean collectively, not by themselves. When you break them down into their individual meanings, they become very different. 無/mu means “no,” 邪/ja means “evil,” and 気/ki means “spirit.” Put them all together, and you get “absent of evil emotion,” i.e. “innocent,” but isolate the middle one, and you’ve just got “evil.”

Ironically, though this is a clear case of a cross-cultural mix-up, the etymology of the Japanese “mujaki” and English “innocent” are actually pretty similar. “Innocent” comes from attaching the “in-“ prefix, which means “not” (like in “incomplete”) to “nocere,” the Latin verb for “to hurt/harm,” making the root meaning of “innocent” essentially “not [intending to] cause harm.”

While it’s possible someone played a trick on the tattooed girl, it’s also possible that the whole thing was a, well, innocent mistake, since apparently at one point she really did have the correct full set of all three kanji in front of her. As for why the tattoo artist didn’t warn her, tattoo artists are artists, not linguists, and hers may not have had any greater understanding of the Japanese language than the woman herself did, especially if she’d found/picked out the kanji before coming into the studio and came with a picture of it and said, “Give me that.”

The whole situation is yet another reminder that if you’re thinking of getting a kanji tattoo, discussing what you really want, including the context, with a Japanese-language expert you can trust is a very good idea. The silver lining is that if the woman wants to, she can still get the missing 無 and 気 kanji tattooed on either side of 邪, provided it’s on a part of her body where there’s enough space. That still leaves the issue that many Japanese people are more likely to associate the word mujaki with child-like straightforwardness than elegant purity, but that’s still better than a straight-up mark of evil.

Source: Twitter/@ToraiKun via Jin

Top image: SoraNews24/Pakutaso

Insert images: SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he wonders if this whole mess could have been avoided if more people outside Japan had played Naxat Soft’s Jaki Crush video pinball game during the 16-bit era.

Japanese lawyer comments on legality of tattoo ban at hot springs, netizens share thoughts too

Japanese lawyer comments on legality of tattoo ban at hot springs, netizens share thoughts too Big win for tattoo artists: Japan’s Supreme Court rules medical licenses aren’t necessary

Big win for tattoo artists: Japan’s Supreme Court rules medical licenses aren’t necessary Kanji fail – Japanese World Cup fans notice Greek player’s strange tattoo

Kanji fail – Japanese World Cup fans notice Greek player’s strange tattoo Family cheated out of 54 million yen by man impersonating Japanese rock star for three years

Family cheated out of 54 million yen by man impersonating Japanese rock star for three years No digital ink here – Yokohama tattoo parlor churning out amazing anime art

No digital ink here – Yokohama tattoo parlor churning out amazing anime art Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience

Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience New Pokémon ice cream, dessert drinks, and cool merch coming to Baskin-Robbins Japan【Pics】

New Pokémon ice cream, dessert drinks, and cool merch coming to Baskin-Robbins Japan【Pics】 New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir

New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan

How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】

High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】 Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters

Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters Caffeinated ramen for gamers that you can eat with one hand going on sale in Japan

Caffeinated ramen for gamers that you can eat with one hand going on sale in Japan Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide

Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration

Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys

Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys “The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】

“The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】 Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan

Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches

McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous?

Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous? Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not

Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists

Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners

To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners 10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan

10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear

Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka

Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model

Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose

Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】

Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】 Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Tokyo hot spring allows guests with tattoos to bathe… with some very odd restrictions

Tokyo hot spring allows guests with tattoos to bathe… with some very odd restrictions Solaniwa Onsen: Kansai’s largest hot spring theme park is also one of its most beautiful

Solaniwa Onsen: Kansai’s largest hot spring theme park is also one of its most beautiful Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character

Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character Kanji T-shirt seen on U.S. TV show makes Japanese viewers giggle

Kanji T-shirt seen on U.S. TV show makes Japanese viewers giggle Renowned Japanese calligraphy teacher ranks the top 10 kanji that foreigners like

Renowned Japanese calligraphy teacher ranks the top 10 kanji that foreigners like Korean tattoo artist’s small, simple, stylish “line tattoos” change our impression of getting inked

Korean tattoo artist’s small, simple, stylish “line tattoos” change our impression of getting inked Tattooed Japanese woman suing nursing school after being suspended because of her ink

Tattooed Japanese woman suing nursing school after being suspended because of her ink Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet

Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet Government begins study into tattoo bans in public baths

Government begins study into tattoo bans in public baths Japan’s Kanji of the Year revealed, reflects both the good and the bad of 2022

Japan’s Kanji of the Year revealed, reflects both the good and the bad of 2022 The hidden meaning of the U.S. Air Force’s “shake and fries” patch in Japan

The hidden meaning of the U.S. Air Force’s “shake and fries” patch in Japan Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice

Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice Draft bill proposal seeks to curtail unconventional “kirakira” kanji name readings in Japan

Draft bill proposal seeks to curtail unconventional “kirakira” kanji name readings in Japan This squirrel is sub-par! More nonsense Japanese hits the fashion market

This squirrel is sub-par! More nonsense Japanese hits the fashion market Onsen in Nagano will now welcome foreigners with tattoos, as long as they patch ’em up

Onsen in Nagano will now welcome foreigners with tattoos, as long as they patch ’em up Japanese Self-Defense Force mulls removing its ban on tattoos

Japanese Self-Defense Force mulls removing its ban on tattoos

Leave a Reply