Linguistics professor explains the centuries-old background of the omnipresent anime and manga verbal tic.

If you’re studying Japanese, three of the first words you’ll learn are arimasu, imasu, and desu. While they all more or less translate into English as “be,” they’re used for different situations in Japanese.

Arimasu is for showing the existence or location of inanimate objects. For example, if you wanted to say “Mt. Fuji is in Japan,” you’d say “Fujisan ha Nihon ni arimasu.” Imasu, on the other hand, is for the existence/location of people and animals. So for “I am in Japan,” it’d be Watashi ha Nihon ni imasu.” And finally, desu is used with adjectives that describe the condition of things or people. “Mt. Fuji is beautiful” is “Fujisan ha kirei desu,” and, if you’re confident enough to make the same boast about your own fetching good looks, it’d be Watashi ha kirei desu.”

But in the world of anime and manga, if the scriptwriter or author is creating dialogue for a Chinese character who’s supposed to be less than fluent, there’s a better-than-even chance the character will completely bypass imasu and desu and just use arimasu, or it’s more casual version, aru, for everything. Instead of the grammatically correct “Watashi ha Chugokujin desu” (“I am Chinese”), you’ll often hear Chinese characters saying “Watashi ha Chugokujin arimasu.”

The weird thing, though, is that you’ll rarely, if ever, hear actual Chinese learners of Japanese putting arimasu at the end of everything like this. So where does this stock speaking style for anime and manga come from? According to Satoshi Kinsui, a linguistics professor at Osaka University, it comes from history.

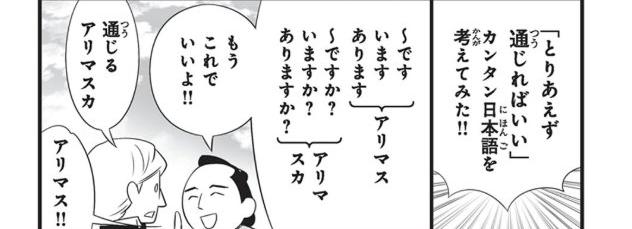

Manga artist Hebizo and author Umino Nagiko asked Kinsui about the “Chinese people say arimasu” stereotype as part of the research for their new book, Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3 (“Japanese Language that Japanese People Don’t Know 3”). Kinsui says this overreaching use of arimasu has its roots in the mid-19th century, as Japan’s feudal Edo period was coming to an end and the modernization of the Meiji period was beginning.

▼ Cover of Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3

With Japan finally opening up to international trade and relations after centuries of government-mandated isolation, there was a sudden influx of foreigners coming into the country. However, this was long before online dictionaries, budget-priced phrasebooks, or other easy ways to bridge low-to-moderate language barriers. So instead, a simplified, pidgin-like version of Japanese came about, in which arimasu, imasu, and desu all got lumped together as arimasu.

▼ One of Hebizo’s illustrations for the book, showing a topknotted Japanese local explaining to a light-haired Westerner that he can still make himself understood even if he lumps desu (です), imasu (います), and arimasu (あります) all together as just arimasu.

But as the caricatured Kinsui himself points out, this form of simplified Japanese was used by foreigners of many different nationalities, not just those who spoke Chinese as their native language. So why has the verbal tick been attached so firmly to Chinese anime characters?

Kinsui himself doesn’t address the question, but a couple of possibilities come to mind. First, Kinsui mentions that the “everything is arimasu” style of pidgin also seems to have been used in Japanese-occupied China, with the Imperial Japanese Army holding on to those territories until the end of World War II. On the other hand, few foreigners were coming into Japan during its era of military aggression. Once the war was over many of the foreigners in the country were part of the occupying Allied Forces, and the balance of power became such that Japanese businessmen and politicians were now expected to be able to communicate in English for international affairs. That would make the era of arimasu-style pidgin a few decades more recent among native speakers of Chinese than other languages, and could be why Chinese anime characters are so much more likely than any other ethnicity to speak that way.

▼ A selection of pages from Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3

アニメの博士はなぜ「~じゃ」と話すのか。謎の中国風キャラはなぜ「アルヨ」と話すのか。実際にそんな人見たことないのに!

— 蛇蔵@天地創造デザイン部8巻発売中 (@nyorozo) November 3, 2018

という疑問に答える漫画を描いたことがあるのでどうぞ。https://t.co/hXaliIfPXc pic.twitter.com/XrMg1MvHqV

There’s also the practice that when looking for dialogue-based ways to emphasize a character’s foreignness, if said character is from a Western background, anime creators often just have the character speak English, or pepper their Japanese dialogue with English vocabulary that Japanese audiences will be at least somewhat familiar with. English is a required subject in Japanese schools, and loanword-loving Japanese has adopted a large number of English terms, so it’s a simple matter to have, for example, an American character suddenly say “Great!” instead of “Ii na! or “Me ha very happy desu,” instead of “Watashi ha totemo shiawase desu.”

Doing that makes the character still sound foreign, but also leaves the dialogue understandable to a Japanese audience (even if the English isn’t being used like an actual English-speaker would use it). But with the average Japanese person far less familiar with basic Chinese vocabulary, that’s not a viable dialogue-writing option, leaving many creators falling back on just slapping arimasu at the end of Chinese characters sentences.

▼ English being a required subject also no doubt makes it easier to ask anime voice actors to power through a few lines of English dialogue than to do the same with Chinese.

Granted, anime and manga are first and foremost entertainment media, and having a simple way of telling he audience “This person isn’t a Japanese national” lets creators quickly move on to what they want to focus their storytelling on. Still, the fact that real world Chinese natives who’re learning Japanese don’t put arimasu at the end of all their sentences can be irksome and distracting for anyone who’s spent much time around learners of Japanese as a second language.

Source: Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3, Twitter/@nyorozo

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3, Twitter/@nyorozo

[ Read in Japanese ]

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he has to admit he is fond of using the word “GET!” when speaking Japanese.

[ Read in Japanese ]

Japanese Twitter rolls eyes at book teaching “manners 90 percent of Japanese people don’t know”

Japanese Twitter rolls eyes at book teaching “manners 90 percent of Japanese people don’t know” Five magic Japanese phrases to know before starting a job in Japan

Five magic Japanese phrases to know before starting a job in Japan Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them

Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them Foreign shop clerk and Japanese customer fail to communicate because of Japanese language quirk

Foreign shop clerk and Japanese customer fail to communicate because of Japanese language quirk Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month Beautiful Sailor Moon manhole cover coasters being given out for free by Tokyo tourist center

Beautiful Sailor Moon manhole cover coasters being given out for free by Tokyo tourist center Arrest proves a common Japanese saying about apologies and police

Arrest proves a common Japanese saying about apologies and police Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it?

Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it? Our reporter takes her 71-year-old mother to a visual kei concert for the first time

Our reporter takes her 71-year-old mother to a visual kei concert for the first time Tokyo’s super-secret-location sushi restaurant has a stand-up sister shop that’s open to all

Tokyo’s super-secret-location sushi restaurant has a stand-up sister shop that’s open to all Japan spending survey shows one region really likes to drink

Japan spending survey shows one region really likes to drink Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community

We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】

Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】 Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park

There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball

Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down

Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train

Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules

Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears?

Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears? New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure

Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure Japan’s Kinki University decides to change its naughty-sounding name

Japan’s Kinki University decides to change its naughty-sounding name Japanese bag looks like it’s spouting random English, but has an actual message

Japanese bag looks like it’s spouting random English, but has an actual message Japanese version of Frozen 2’s “Into the Unknown” is a powerful return for Elsa’s singer in Japan

Japanese version of Frozen 2’s “Into the Unknown” is a powerful return for Elsa’s singer in Japan Five ways to piss off your older Japanese coworkers at a new job

Five ways to piss off your older Japanese coworkers at a new job Textbook gives Chinese otaku Japanese lessons with a side of anime girls and dialogue

Textbook gives Chinese otaku Japanese lessons with a side of anime girls and dialogue Japanese tourist center asks small-penised travelers to not make a mess in the bathroom

Japanese tourist center asks small-penised travelers to not make a mess in the bathroom Restaurant in Indonesia’s bizarrely translated Japanese menu commands customers to get stabbed

Restaurant in Indonesia’s bizarrely translated Japanese menu commands customers to get stabbed English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect

English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect Director of The Boy and the Beast, Summer Wars explains why he rarely casts anime voice actors

Director of The Boy and the Beast, Summer Wars explains why he rarely casts anime voice actors Japanese Twitter user embarrassed to learn why American friend is studying Japanese, not Chinese

Japanese Twitter user embarrassed to learn why American friend is studying Japanese, not Chinese Anime-style magical girl video series promotes good subway manners…in Los Angeles?!?【Videos】

Anime-style magical girl video series promotes good subway manners…in Los Angeles?!?【Videos】 The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu”

The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu” Donald Trump fronts Twitter ads on Japan’s rail network【Photos】

Donald Trump fronts Twitter ads on Japan’s rail network【Photos】 “Amazing Kyoto” shows us sides of Japan’s old capital we’ve never seen before — in two languages!

“Amazing Kyoto” shows us sides of Japan’s old capital we’ve never seen before — in two languages! RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese

RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese

Leave a Reply