We step back into the past on a walk to the Akechi Thicket.

Kyoto is one of Japan’s top travel destinations, drawing visitors who dream of sipping green tea, touring temples and gardens, and otherwise immersing themselves in the city’s storied atmosphere of refined tranquility. But while Kyoto is the cultural capital of Japan, for several centuries it was the political one too, which means the city was sometimes the site of violent power struggles during the feudal era.

So today, we’re going off the beaten path in Kyoto and instead following the path of a beaten samurai, as we retrace the final steps of Akechi Mitsuhide, one of Japan’s most infamous warlords who met his end in Kyoto more than 400 years ago.

▼ Akechi Mitsuhide

Mitsuhide rose to prominence as a retainer of Oda Nobunaga, one of Japan’s three great unifiers who nearly ended Japan’s centuries-long civil war now called the Sengoku period. However, with Nobunaga close to suppressing the last bits of resistance to his rule, he was betrayed by Mitsuhide, who ambushed his master while he was lodging at Kyoto’s Honnoji Temple, resulting in Nobunaga committing seppuku (ritual suicide) when his defeat appeared certain.

▼ Honnoji Temple

But while Mitsuhide’s betrayal was successful, his follow-up plans were not. He failed to win wide support from the other Oda retainers, and so found himself the target of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, another Oda general who had remained loyal to his liege. Hidetomi, who had been fighting in western Japan, quickly brought his troops back to Kyoto and routed Mitsuhide’s forces at the Battle of Yamazaki, forcing Mitsuhide to give up his position at Kyoto’s Shoryuji Castle in Kyoto and flee for his home fortress of Sakamoto Castle, located east of Kyoto on the banks of central Japan’s Lake Biwa.

▼ Shoryuji Castle

However, Mitsuhide would never make it home. Instead, he would meet his end in a spot now known as Akechi Yabu, or the Akechi Thicket, which is located in present-day Kyoto City’s Fushimi Ward.

▼ Shoryuji Castle (red arrow), Akechi Thicket (green arrow), and Sakamoto Castle (blue arrow)

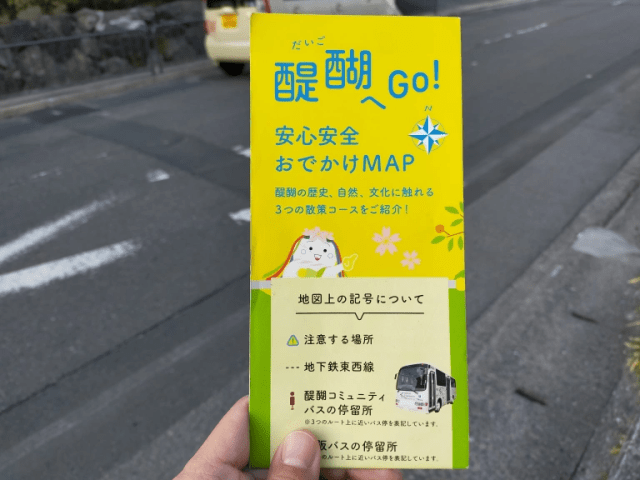

The thicket is within walking distance of Daigo and Ishida stations on the Kyoto subway network, which also has free maps of the local area.

Getting off the train at Daigo Station, we headed out of the gates and made our way up the Ogurisu-gaido road. Eventually, we turned down a narrow pedestrian path.

We came out on the far side, and after walking a little further into the interior, we saw a placard placed amidst shrubbery and bamboo stalks, telling us that we’d arrived at Akechi Thicket.

Historians say that this is where Mitsuhide was hunted down and slain by mountain bandits. Obviously, there’re no brigands in the neighborhood today, and while the area isn’t by any means urbanized, it’s still a modern, if sparsely populated, community.

Still, the contours of the mountains are essentially unchanged, and it’s hard not to wonder if they were the last things Mitsuhide saw before the ultimate, fatal unraveling of his ploy.

Like with a lot of prominent figures from Japan’s feudal period, Mitsuhide’s legacy is one without a clear-cut good-or-bad judgment from historians and the Japanese people at large. Some see him as a malicious and deceitful figure, while others find justification for his actions in Nobunaga’s own penchant for ruthless methods in trying to tighten his grip on the reins of Japan.

▼ The nearby Honkyoji Temple has a memorial stone for Mitsuhide

But for those looking to literally trace the path of someone who played a significant role in shaping the nation’s history, a visit to the Akechi Thicket is a unique alternative to the standard Kyoto temples and gardens.

Top image ©SoraNews24

Insert images: Wikipedia/GooGooDoll2, Wikipedia/KENPEI, Wikipedia/File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske), SoraNews24, Google (edited by SoraNews24)

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Follow Casey on Twitter, where learning about the Honnoji Incident was the first thing that sparked his interest in Sengoku period history.

Recreating the greatest betrayal of the samurai era with the Honnoji Incident papercraft kit【Pics】

Recreating the greatest betrayal of the samurai era with the Honnoji Incident papercraft kit【Pics】 Eat like a treacherous samurai! Kyoto restaurant recreates a real-life warlord’s favorite food

Eat like a treacherous samurai! Kyoto restaurant recreates a real-life warlord’s favorite food Eat like a samurai from the warring states period with new range of canned meals from Japan

Eat like a samurai from the warring states period with new range of canned meals from Japan Hotel in Osaka offering shaved ice based on historical Japanese warlords

Hotel in Osaka offering shaved ice based on historical Japanese warlords Site of Japan’s most famous samurai murder is now a Kyoto karaoke joint

Site of Japan’s most famous samurai murder is now a Kyoto karaoke joint Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is

Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of

Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Adorable Totoro acorn key holders come with a special guest hidden inside[Photos]

Adorable Totoro acorn key holders come with a special guest hidden inside[Photos] The massive Pokémon card public art display going on in Japan right now is a thing of beauty【Pics】

The massive Pokémon card public art display going on in Japan right now is a thing of beauty【Pics】 Japanese potato chip Rubik’s Cubes coming soon

Japanese potato chip Rubik’s Cubes coming soon Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism What’s in a Family Mart lucky bag?

What’s in a Family Mart lucky bag? Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism”

Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism” The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens

Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens Playing Switch 2 games with just one hand is possible thanks to Japanese peripheral maker

Playing Switch 2 games with just one hand is possible thanks to Japanese peripheral maker Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】

Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】 Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says The time farting lead to murder and the fall of one of Japan’s great samurai clans

The time farting lead to murder and the fall of one of Japan’s great samurai clans Nightingale floors: The samurai intruder alarm system Japan’s had for centuries

Nightingale floors: The samurai intruder alarm system Japan’s had for centuries Kyoto samurai house wants to share its history of seppuku, torture and gold coins with visitors

Kyoto samurai house wants to share its history of seppuku, torture and gold coins with visitors No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 4】

No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 4】 The restaurant where one of Japan’s last samurai lords ate now has a café with really good cake

The restaurant where one of Japan’s last samurai lords ate now has a café with really good cake Visiting Kyoto’s Pool of Blood — A ghost-hunting alternative to the city’s temples and shrines

Visiting Kyoto’s Pool of Blood — A ghost-hunting alternative to the city’s temples and shrines The all-new Kyotrain, maybe Japan’s most Japanese train ever, will take you to Kyoto this spring

The all-new Kyotrain, maybe Japan’s most Japanese train ever, will take you to Kyoto this spring Kyoto sightseeing tour: The most amazing old bathhouses in the city

Kyoto sightseeing tour: The most amazing old bathhouses in the city Visiting Kunozan Toshogu, the shrine where the first lord of Japan’s last shogunate was buried

Visiting Kunozan Toshogu, the shrine where the first lord of Japan’s last shogunate was buried Why does Japan’s most famous ocean legend end at this temple in the middle of the mountains?

Why does Japan’s most famous ocean legend end at this temple in the middle of the mountains? No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 1】

No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 1】 Don’t let the rain get you down! Here are Japan’s top 10 most beautiful rainy day travel spots

Don’t let the rain get you down! Here are Japan’s top 10 most beautiful rainy day travel spots No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 3】

No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 3】 No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 2】

No-bus Kyoto sightseeing! SoraNews24’s ultimate on-foot guide for Japan’s former capital【Part 2】 Beautiful Starbucks in Kyoto blends into its traditional landscape in more ways than one

Beautiful Starbucks in Kyoto blends into its traditional landscape in more ways than one