Take it from someone who actually had to quarantine — the rules are harder to follow than you may think.

People re-entering Japan from abroad has become a bit of a hot topic in the Japanese media lately, with reports claiming that up to 300 people a day are breaking the quarantine rules.

That’s not to say everyone who returns from abroad is purposely breaking the rules, though, as the quarantine requirements in Japan have been criticised for being vague and less straightforward than those in other countries.

Our reporter Katie Pask recently experienced the Japanese quarantine system firsthand, after she had to return to the U.K. for a family emergency, and as a result, she has some tips below for others going through the process, and also some ideas as to why people may (or may not!) be seen to be breaking these quarantine rules.

So what are the rules?

All passengers flying into Japan are required to provide a negative COVID-19 test result taken within 72 hours of their flight. They are horrendously strict about this. An acquaintance of mine got turned away at the airport in Tokyo because their test was mere minutes over the 72-hour limit, so make sure you work out the timing accurately.

Once you enter Japan, all arrivals are required to quarantine for 14 days. If you are from a ‘high-risk’ country like the U.K., the government will put you up in a hotel for the first few days. After those three days are up you must spend the remaining days quarantining in a place of your choice, but you can’t use any kind of public transport to get there.

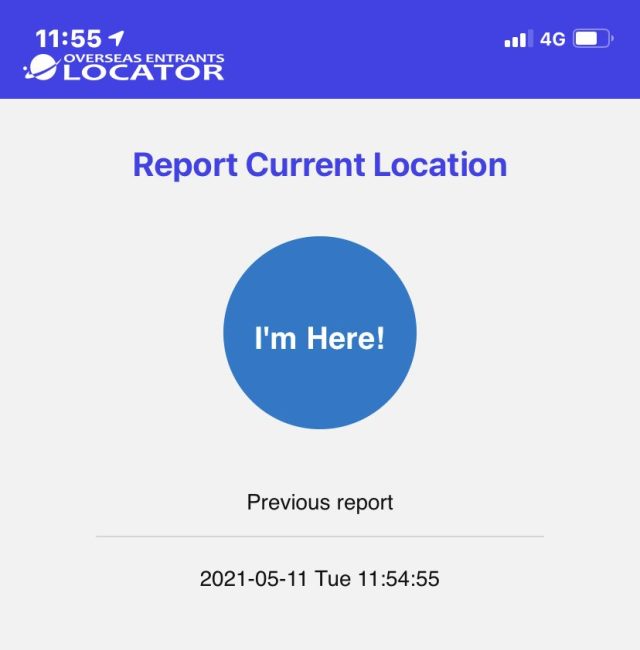

During the 14-day quarantine, you are required to report your location using the Overseas Entrant Locator app. A couple of times during the day at random, a notification will pop up on your phone asking you to report your current location. If you ignore these requests, it may result in you getting deported and your visa status revoked, so be sure to report your location when asked.

▼ Touch the blue ‘I’m Here!’ button to automatically report your GPS location to immigration when asked

You also need to respond to an e-mail questionnaire about your health sent daily. I got mine every day without fail at 11:03 a.m. Again, failure to respond to this (by 2 p.m. daily) can also result in you getting into a lot of trouble.

At any given time, immigration staff may video-call you to check your surroundings. For me, this was via Skype and WhatsApp, but since I completed my quarantine the system has been changed, and now new arrivals will be called via the MySOS app.

To confirm you have understood everything, all new arrivals are required to sign a written pledge, a form which lists all the rules above.

Day Zero – clearing immigration

The moment you step foot in Japan is considered ‘day zero‘ — whether it’s first thing in the morning or last thing at night, it doesn’t count as one of your quarantine days. Luckily for me, my flight landed at Haneda Airport at around 5 o’clock in the evening, meaning most of my day was already done. After we landed, the airport staff let us out by rows to stop crowding. As I walked into the airport, I was immediately approached by a member of staff who, without any explanation, put a long, green tag around my wrist.

What followed was something resembling an escape game. Dotted about the airport were booths, and each booth had a different requirement to ‘clear’ it — some of them required you to show some papers, some of them you needed to install apps and so on. I recommend getting as much stuff prepared and downloaded before you get on a plane if you want to make your experience as smooth as possible — I had the Overseas Entrant Locator app, the COCOA app and WhatsApp already installed, and printed all my documents ready to show. The situation is constantly changing, though, so be sure to check the current requirements online for the most up-to-date information.

One of the areas was a COVID-19 testing station. I was given a test tube, directed into a small booth and asked to spit into the tube. The walls of the booth were decorated with pictures of lemons and umeboshi (very sour pickled plum) to get your mouth full of saliva.

▼ Just glancing at this picture of umeboshi already has my mouth flooded.

Image: Pakutaso

I should mention at this point, I had been supervised by airport staff the entire time. I was not once let out of their sight. Even when I needed to use the restroom, I was chaperoned by a member of staff. There is no opportunity to break off for a quick visit to the convenience store, or to pick up any SIM cards, etc. There are also no vending machines, and the process can take a long time. I definitely recommend bringing a snack and a drink to keep you going, as the whole process for me took almost four hours.

▼ About half of the paperwork I needed to clear immigration.

Once I’d had all my checks, got all my papers stamped and signed and got a negative result from my COVID-19 test, it was off to the hotel. As the U.K. was considered a ‘high-risk’ country, my first three days were to be spent in government-funded quarantine, so I was herded onto a coach with five other people. I had absolutely no idea where I was going; the front of the bus was helpfully labeled ‘Hotel F’. Before we got on the bus, our green wrist tags were removed.

After about a thirty-minute coach ride, we arrived at the hotel. I was staying at the Yokohama Bay Tower hotel, and the lobby had been specially set up for us new arrivals. There were booths with hotel staff in full PPE stationed at each one, ready to explain the rules of the hotel quarantine to us in both Japanese and English if required. The rules seemed clear enough: absolutely no leaving your room at any point. Deliveries from Amazon were okay, but food deliveries like UberEats were not. We would be served meals three times a day. On the third day we would undergo another saliva test, and if we were negative, we were free to leave.

I was guided up to my hotel room by a man wearing a lot of PPE, and that was it. The first chance I had to be alone in about 30 hours. Bliss!

Day One to Three — Government-Provided Accommodation

Day One for me started at about 3 a.m., as I was still heavily suffering from jet lag. I woke up, looked out of the window and realised I had the entire three days ahead of me with absolutely nothing to do. This could be my chance to do something incredible, with all this free time! I could start to learn a new language, or take up yoga, or write a novel — this could be the beginning of something life-changing.

So I decided to download Pokémon Snap.

The three days in the hotel went by very slowly. As the hotel room was quite small, I was constantly rotating between my desk and my bed. I tried to be productive, and even considered taking part in a coding course, but cabin fever took hold of me quickly. The mind-numbing boredom mixed with jet lag meant on day three I ended up doing weird things like taking three or four baths in a day, just to give me something different to do. When I did manage to get to sleep, it was never for long, as I had spent most of my day sitting down, so I never really used enough energy to make myself tired.

▼ I also decided to join TikTok, although I’m not very good at it.

Meals turned out to be a mini-highlight of the day, and also a way to keep track of time. Meals were served three times a day, and left outside on your door handle. Before arriving in Japan, I’d read online that the meals provided could at times be somewhat… lacking, so I prepared ahead and brought some snacks in my suitcase to help keep me going. I don’t eat fish, so I opted for the vegetarian menu, which seemed to consist of pasta, pasta and more pasta. All of the meals were served cold.

Day Four to Fourteen – Private Accommodation

On the morning of day three, we were given a saliva test and if it showed negative, we were free to leave. Luckily mine was negative, so it was with overwhelming happiness that I bid my hotel room farewell on the morning of day four, got back on the hotel bus and made my way back to Haneda Airport.

Once this part of your quarantine is done, you can complete the last 11 days of your quarantine anywhere, provided you don’t make contact with people outside of the people you live with. Ideally, I would have liked to have spent the remaining days of my quarantine in my apartment in Oita Prefecture, but…

Unfortunately, my apartment is a little far from Haneda. As new arrivals are not allowed to take any public transport (including airplanes) and I didn’t fancy walking 904 kilometres (562 miles) with all my luggage, I had to find somewhere in Tokyo where I could spend the last 11 days.

I ended up staying in an apartment run by a company called MetroResidences, who have packages designed for new arrivals, as I didn’t want to spend eleven days without a kitchen or washing machine. The company even sent someone to pick me up from the airport and take me to the apartment, which was an absolute lifesaver. In this apartment, I had a lot more space and also a lot more freedom…or so I thought.

From what I had read online, it seemed that once you were out of the government quarantine, you would be able to go outside to get groceries or medicine. But that seemed like a direct contradiction to the written pledge all new arrivals signed upon their arrival into Japan, which clearly stated that you had to ‘stay at home’.

From the written pledge —

(a) You must stay at home or the accommodation.

(b) You must not have contact with anyone who you do not live with.

“You must stay at home” could mean “you must not leave your house” or it could mean “you shouldn’t go to school/work”. “You must not have contact with anyone who you do not live with” could mean “You must not see anyone who is not in your household” or “keep a safe distance from people not in your household”. The language used in the pledge is arguably quite vague, and can easily be interpreted differently, depending on who is reading it.

As luck would have it, as I was pondering whether or not to make a quick visit to the nearby supermarket, I got a video phone call from Immigration. After confirming my location, I decided to ask the immigration officer, who said we were allowed to go outside “if it were necessary”.

What does necessary mean, though? And does one immigration officer’s comment necessarily hold any weight? I didn’t feel like my question had been properly answered and so to stay on the safe side, I decided to spend the whole eleven days without setting a foot outside my apartment.

▼ Amazon got a lot of business from me over the past two weeks.

▼ For anyone who wants to avoid UberEats every day, Amazon Life lets you shop for groceries sourced from nearby supermarkets.

Day Fifteen – freedom!

On the morning of day fifteen, I finally took a step outside my apartment door. I was met with some questionable weather — the rainy season looked as if it had just started and it was a grey, miserable morning, but it was so amazing to feel the cool wind on my face and see things other than the walls of my apartment. I even found beauty in the boxes of trash nestled on the street.

▼ Tokyo, you’ve never looked more beautiful.

I managed to navigate the Tokyo subway, suitcases in tow, hopped on an airplane and it was back to Oita.

▼ I’m home!!

So why are so many people breaking the rules?

If the statistics are true, I feel that the majority of these ‘rule-breakers’ may be going against the rules unintentionally.

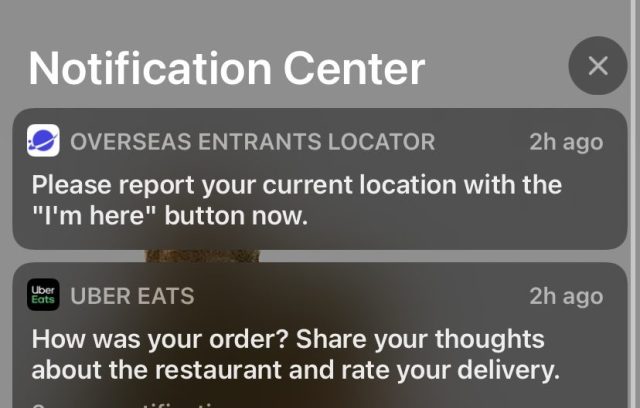

For a start, the system itself has some problems. I’ve read multiple cases where people hadn’t received the daily health-check questionnaires, or never got told the username and password needed to log into the tracking app. And it’s also possible for the daily notifications requesting your location details to go unnoticed for several hours if you’re not checking your phone at regular intervals.

If you find yourself in any of those situations, there’s a chance you might fall into the category of a supposed ‘rule-breaker’ so you really have to be diligent and pro-active throughout the whole process.

▼ Be sure to check the Notification Center often to catch those notifications

Secondly, there is a lot of conflicting information. The written pledge tells you to stay at home, but also to wear a mask and wash your hands often. Why would this be necessary if you were staying indoors the whole time? There is no line in the pledge specifically forbidding you from going outside, and maybe it’s this vague wording that is causing a lot of confusion.

So while there may be people entirely aware of the rules and breaking them intentionally, I really doubt this can be said for all 300 of the alleged ‘rule-breakers’ that the media has been reporting. Unless changes to the Japanese quarantine system are made, the number of people being classed as rule-breakers — whether the rules were broken intentionally or not — are unlikely to decrease any time soon. Although from the looks of how things are going, there might be less people needing to quarantine in the first place — at least from the U.S., anyway.

Related: Return to Japan Support Group (Facebook), MetroResidences

Featured image: Pakutaso

Insert images © SoraNews24 unless otherwise noted

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Up to 300 people a day breaking Japanese quarantine rules, according to reports

Up to 300 people a day breaking Japanese quarantine rules, according to reports Foreign Reuters journalist in Tokyo spreads mutant strain of coronavirus

Foreign Reuters journalist in Tokyo spreads mutant strain of coronavirus Travellers sleep on cardboard beds at Narita Airport while waiting for coronavirus test results

Travellers sleep on cardboard beds at Narita Airport while waiting for coronavirus test results Travelling to Japan soon? New entry requirements you need to know about

Travelling to Japan soon? New entry requirements you need to know about Survey results reveal average number of days people can bear to self-quarantine

Survey results reveal average number of days people can bear to self-quarantine Last chance coming up for amazing east Japan for all-you-can-ride Shinkansen-inclusive train pass

Last chance coming up for amazing east Japan for all-you-can-ride Shinkansen-inclusive train pass Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years

Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Fried sandwiches arrive in Tokyo, become hot topic on social media

Fried sandwiches arrive in Tokyo, become hot topic on social media Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Survey finds Japan to be least god-fearing nation in the world and it’s not even close

Survey finds Japan to be least god-fearing nation in the world and it’s not even close Eight Ways You Really, Really Shouldn’t Use a Japanese Toilet

Eight Ways You Really, Really Shouldn’t Use a Japanese Toilet Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens

Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】

Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】 Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning looks to be affecting tourist crowds on Miyajima

China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning looks to be affecting tourist crowds on Miyajima Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Quarantined cruise ship finally ready to sail again, leaves a heartwarming message of thanks

Quarantined cruise ship finally ready to sail again, leaves a heartwarming message of thanks 100 mild and no-symptom coronavirus patients in Tokyo set to be relocated to hotel for quarantine

100 mild and no-symptom coronavirus patients in Tokyo set to be relocated to hotel for quarantine Worker at Narita airport accidentally drops coronavirus reagent, contaminates whole room

Worker at Narita airport accidentally drops coronavirus reagent, contaminates whole room We spend five days trapped in a hotel room for our ‘Isolation Experiment’

We spend five days trapped in a hotel room for our ‘Isolation Experiment’ Search is on for COVID-19 patient who escaped out a sixth-floor window of Osaka hotel

Search is on for COVID-19 patient who escaped out a sixth-floor window of Osaka hotel Travelers entering Japan will have to install location confirmation app, Skype on smartphones

Travelers entering Japan will have to install location confirmation app, Skype on smartphones This Tokyo coronavirus quarantine facility’s bento boxed meals are amazingly good【Taste test】

This Tokyo coronavirus quarantine facility’s bento boxed meals are amazingly good【Taste test】 Pocari Sweat offers free self-care packages for those battling COVID-19 at home

Pocari Sweat offers free self-care packages for those battling COVID-19 at home Japanese divorce rate drops nearly 10 percent during quarantine, netizens try to figure out why

Japanese divorce rate drops nearly 10 percent during quarantine, netizens try to figure out why Travelling to Japan soon? Beware the “Three Small Hells” awaiting tourists upon arrival

Travelling to Japan soon? Beware the “Three Small Hells” awaiting tourists upon arrival American woman arrested after throwing away massive supply of bullets in Tokyo airport trash can

American woman arrested after throwing away massive supply of bullets in Tokyo airport trash can What to expect when traveling abroad from Japan in a global pandemic

What to expect when traveling abroad from Japan in a global pandemic Japan once again closes borders to foreign travelers with new entry restrictions

Japan once again closes borders to foreign travelers with new entry restrictions Hankering for a vacation? Try these pseudo-vacations offered in Taiwan and Japan

Hankering for a vacation? Try these pseudo-vacations offered in Taiwan and Japan Everything you need to know about climbing Japan’s second-highest volcano

Everything you need to know about climbing Japan’s second-highest volcano Japanese government appoints hikikomori as head of council on “self-quarantine strategies”

Japanese government appoints hikikomori as head of council on “self-quarantine strategies”