They asked Seiji if he wanted to get into the real estate game, but Seiji wanted to know how they got his number.

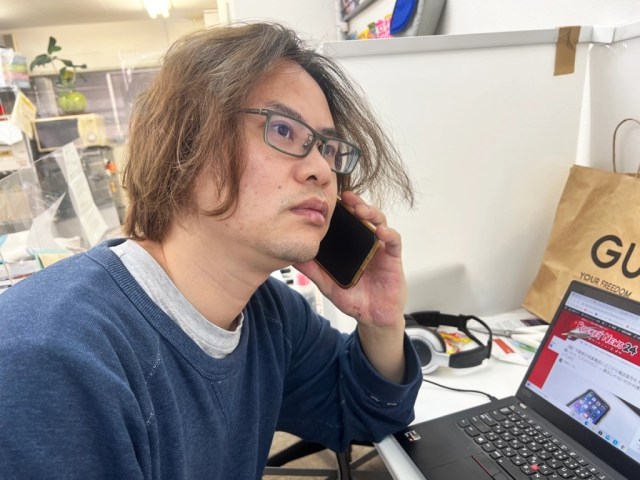

Like a lot of people these days, our Japanese-language reporter Seiji Nakazawa primarily keeps in touch with friends and family through text messages and voice chat apps. If someone does call his actual phone number, it’s usually either a company or individual he’s reached out to while researching an article or someone trying to sell him something, and when his phone rang the other day, it was the latter.

“Hello, Mr. Nakazawa!” said the voice on the other end of the line, before introducing himself and giving the name of his company. Seiji had never heard of either of them, but for the purposes of this article, we’ll call the man Nishida from Company P. Company P, he said, was a real estate services provider, and he wondered if he might be able to interest Seiji in som–

“No, I’m not interested,” Seiji said, cutting Nishida off before he could waste any more of either of their time. “If I could just have a few moments to explain our system,” Nishida pleaded, and in fact Seiji did want to know about Company P’s system…but not the one by which they buy and sell real estate,

“How did you get my phone number?” Seiji asked.

We know it’s hard to believe, what with his massive 20-yen (US$0.17) royalty check from his side business as a recording artist, but Seiji is neither a wheeler nor a dealer in the real estate market, and he’s never hired the services of any sort of property development/investment firm.

▼ Seiji, seen here cooking his lunch on the hood of a car, does not lead a Rockefeller-esque life.

“I saw your name listed on our name list, and contacted you via the phone number it has for you,” Nishida answered. Of course, this just made Seiji want to know how Company P got the name list, and Nishida told him “We purchased it from a name list company.”

Seiji appreciated Nishida’s honesty, but each answer just led him to another question. Just like Seiji didn’t recall giving his personal information to any real estate investment companies, he also has no recollection of giving it to a name list company for them to pass off to Company P. Hoping to finally get to the bottom of the mess, he asked Nishida what the name of the name list company was, and this is where Nishida stopped being helpful. “I’m sorry, but our company does not divulge such information.”

That didn’t sit right with Seiji. Up until this point, he’d been warming up to Nishida, and even thinking that should he turn out to be the member of the SoraNews24 who finally does win the lottery, he might have Nishida broker the purchase of his villa. But now Nishida was blocking his attempt to find out more about the name list company, even though both Company P and the name list supplier knew more about Seiji than he was comfortable with.

So after Seiji hung up, his next phone conversation was with Ryo Furukawa, a lawyer with Tokyo’s Hirano Law Office. Isn’t what happened to Seiji a violation of Japan’s Personal Information Protection Law?

Unfortunately, it’s probably not, Furukawa informed him.

“Selling a name list with the entrants’ personal information, in and of itself, isn’t illegal,” Furukawa explained. “What you have here is a situation where one company supplied another with your personal information, and that second company contacted you using it, but it’s likely the process started with information you yourself willingly provided.”

While Seiji has never given his name and phone number to a name list broker or real estate investment firm, he has, of course, supplied that information to plenty of other businesses over the years that require customers to provide contact information or create user accounts. It’s not unusual, Yoshikawa explained, for such service contracts to include clauses stating that the customer gives consent for their information to be used in solicitation for specific products or services (such as real estate investment) or that it may be supplied to third party organizations. Sometimes there’s even a sneaky additional clause to the effect of “In the event that information is being suppled to a third party, your personal data will be withheld upon request,” but since Seiji would have no way of knowing about such an arrangement ahead of time, he wouldn’t have any way of keeping his name of the list.

As for Nishida refusing to reveal the name of the company that Company P had bought the name list from, that’s not illegal either. While companies are required to keep an internal record of where they obtained the information from, they’re under no legal obligation to divulge it just for the asking, even if they’re being asked by the person whose information it is.

With no evidence, or even implication, that a crime was committed, Seiji doesn’t have any real leverage to force Company P to tell him where they got his information from. Yoshida says, though, that that will change next year, when an amendment to the Personal Information Protection Law will go into effect, obligating companies to reveal their personal information sources if asked by the individual themselves, but for now, Seiji is pretty much out of options.

Well, except one, which is that right here and now he’s officially putting the word out that he’s not interested in any real estate investment pitches. So if you’re a telemarketer who’s reading this article, go ahead and cross Seiji off your name list right now, since calling him definitely isn’t going to land you a sale.

Photos ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Japanese company offers a “little sister rental” service, and our reporter just tried it out

Japanese company offers a “little sister rental” service, and our reporter just tried it out That time Seiji called JASRAC to ask why he didn’t get paid royalties for his song being on TV

That time Seiji called JASRAC to ask why he didn’t get paid royalties for his song being on TV Can you use the fluctuating exchange rate and Japan’s weak yen to make some money? We find out

Can you use the fluctuating exchange rate and Japan’s weak yen to make some money? We find out Tokyo restaurant doesn’t tell you its name unless you ask, makes us appreciate life’s surprises

Tokyo restaurant doesn’t tell you its name unless you ask, makes us appreciate life’s surprises We rent a sister in Japan, act out sibling scenarios with frightening realness 【Video】

We rent a sister in Japan, act out sibling scenarios with frightening realness 【Video】 Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino New giant Pokémon plushie is so big it looks like it could eat you【Photos】

New giant Pokémon plushie is so big it looks like it could eat you【Photos】 A look back on 40 years of Japanese schools banning stuff

A look back on 40 years of Japanese schools banning stuff Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of

Saitama is home to the best strawberries in Japan that you’ve probably never even heard of Princess Mononoke gets first-ever IMAX screenings to show off gorgeous new remaster【Video】

Princess Mononoke gets first-ever IMAX screenings to show off gorgeous new remaster【Video】 Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Fate/stay night and Axe body spray partner up in attempt to make anime fans smell nice

Fate/stay night and Axe body spray partner up in attempt to make anime fans smell nice Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is

Survey finds that one in five high schoolers don’t know who music legend Masaharu Fukuyama is The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu

Starbucks Japan adds new sakura Frappuccino and cherry blossom drinks to the menu Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years

Japan just had its first same-month foreign tourist decrease in four years Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan

Burning through cash just to throw things away tops list of headaches when moving house in Japan Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Dine at Akihabara’s Dorami and get all-you-can-eat mapo tofu, plus delicious dumplings and more

Dine at Akihabara’s Dorami and get all-you-can-eat mapo tofu, plus delicious dumplings and more “Hey, Japanese taxi driver, take us to the best seafood joint in Otaru!”

“Hey, Japanese taxi driver, take us to the best seafood joint in Otaru!” Our reporter Seiji gets a weird package from overseas, meets a friend he didn’t know he had

Our reporter Seiji gets a weird package from overseas, meets a friend he didn’t know he had “Hey, Japanese taxi driver, take us to the best Sapporo ramen place!” – Things don’t go as planned

“Hey, Japanese taxi driver, take us to the best Sapporo ramen place!” – Things don’t go as planned In our search for crispy katsudon, we try a highly recommended place in a Tokyo university town

In our search for crispy katsudon, we try a highly recommended place in a Tokyo university town We take a 100-yen MP3 player for a test drive, live to tell the tale

We take a 100-yen MP3 player for a test drive, live to tell the tale English-language Reddit falls in love with curry restaurant– Can it win our taste tester’s heart?

English-language Reddit falls in love with curry restaurant– Can it win our taste tester’s heart? We find “Yakushima Soba” on a mysterious menu at a souvenir shop at Yakushima Island’s airport

We find “Yakushima Soba” on a mysterious menu at a souvenir shop at Yakushima Island’s airport Our visit to the coolest Book Off used Japanese book store that we’ve ever seen

Our visit to the coolest Book Off used Japanese book store that we’ve ever seen Our lonely reporter goes searching for Japan’s search-for-a-spouse vending machine

Our lonely reporter goes searching for Japan’s search-for-a-spouse vending machine In downtown Tokyo, we talk to a guy who says he’s from Orion’s belt, get called an “idiot”

In downtown Tokyo, we talk to a guy who says he’s from Orion’s belt, get called an “idiot” No car? No problem! We find photogenic hidden gems in Yakushima that are easy to get to

No car? No problem! We find photogenic hidden gems in Yakushima that are easy to get to Our four must-visit saunas in Japan for total relaxation

Our four must-visit saunas in Japan for total relaxation Rent-a-scary person company appears in Japan, seems an awful lot like a straight-up gang

Rent-a-scary person company appears in Japan, seems an awful lot like a straight-up gang We tried out Japan’s new “mask you can wear while you eat”, found a way to make it much better

We tried out Japan’s new “mask you can wear while you eat”, found a way to make it much better We go on our own hunt for “the biggest mountain” to climb in the style of Tokyo Swindlers

We go on our own hunt for “the biggest mountain” to climb in the style of Tokyo Swindlers