If you’ve been to Japan, you may have been told about the two most common table etiquette faux pas, both related to funerals and death. If you’re not very familiar with Japanese customs, these gaffes are way too easy to commit because on the surface, nothing seems obviously wrong with them.

Since we at RocketNews24 believe that unraveling the mysteries of Japanese culture is part of the fun of traveling and even living in Japan, in this article we’re going to explore strange new worlds, seek out new life and new civilizations, and boldly go where no gaijin has gone before: We’re going to reveal the meaning behind the mother of all lunch boxes: the funeral bento. It’s big, it’s bulky, it’s boisterous, and it’s drop-dead gorgeous.

This veritable feast in a box contains a seven-course meal which is big enough to share with the deceased. Yep, that’s right. Join us while we eat with the dead. Read on!

But first let’s explore the two most common table etiquette faux pas that we introduced at the beginning.

It is impolite to stick your chopsticks straight up into a bowl of rice. This is because that very gesture is used at a Buddhist wake and again at memorial services afterwards. To avoid reminding people of funerals while at the dinner table, when you put down your chopsticks for a moment between bites, it is best to use the chopsticks rest made for that purpose.

The second major gaffe is to pass food between two people via chopsticks, or to have two people grabbing for the same piece of food with their chopsticks. By all means use chopsticks to pick up pieces of food, but place the food directly onto the other person’s plate rather than “passing” it to them or having them take it from you. Why? Because at a Japanese cremation, the deceased’s bones are passed from family member to family member and then placed into the urn. Yeah, let’s not remind people of these things at mealtimes, okay?

- Not bento, but Ozen

The word “bento” is used for the common type of boxed food people eat. While this elaborate dinner plate eaten at funerals is also served in a box, it is distinguished from regular bento by using the word Ozen, which indicates food that will be consumed inside the house (or funeral hall) as opposed to a take-out style bento lunch box. If you look up Ozen in the dictionary, you’ll find it is defined as “a small lacquer table.” This is because traditionally this food, which consisted of five dishes (rice, miso soup, pickles, boiled/simmered vegetables and beans) was served on these small tables. The current funeral box, or Ozen, is used as a more convenient way of serving many dishes without having to have a person serving each food individually.

Ozen is derived from the concept of ryo-gu-zen, which when broken down morphologically means “spirit-give-table.” In other words, you are sharing your meal with the recently departed.

“It’s a very romantic idea,” explains Nishu, a Nichiren Buddhist priest. “We want to treat the deceased as if they are still alive.” This theme continues through the ensuing memorial ceremonies for up to 50 years, each time sharing a meal with them. “We see this same idea at Obon (the Festival of the Dead held in August), when we believe our ancestors come back from the dead to visit us.”

- So, what goes into the meal, and why is it so gorgeous?

In the old days Buddhist monks ate shojin ryori, vegetarian food that you can still find served at temples. But nowadays, Japanese monks eat all kinds of food, including meat and fish. “We know we shouldn’t eat living things, but these days we do eat them, while knowing it is not so good. This is part of the ambivalence of the Japanese,” says Nishu.

Ozen has a base of rice and vegetables. Everything else is extra. Adding a variety of foods makes a more impressive meal and at a funeral, it is felt that people will be more satisfied. Over the years, these meals have been infused with roast beef, raw fish and tempura, making them more gorgeous. “This makes everyone happy,” says Nishu.

▼Juicy slices of roast beef on a leaf of lettuce with parsley and a mini tomato. Does this make you happy?

▼How about this fresh baby squid with lemon? You’re definitely smiling now.

The wife of the Shingon Buddhist priest in our community further elaborates on the custom of shojin ryori. “From the day a person dies until their funeral, the immediate family shouldn’t eat any meat or fish.” This period is approximately three days. “A good Buddhist will eat only vegetables and rice until after that day.” Since the first meal after the funeral is the bento, this may also be a sign of crossing the barrier back into normal life in its myriad symbolic ways, including the gastronomical.

Ozen are sure to feature seasonal food, as the seasons are very important in Japan, even for funerals. The inclusion of a young bamboo shoot or a baby squid shows it is early spring since it is only in these seasons that this food is available. For the immediate family, these foods may serve as poignant reminders of their loved one for years after. My next door neighbor tends to recall that her father-in-law died in the spring, rather than giving the month, for example.

▼A conspicuous bamboo shoot announces the season while resting on top of a piece of broccoli, a shellfish, and a slice of fish paste.

▼Tempura is often served with salt or a mixture of salt and macha.

▼Foliage is always an important part of Japanese food presentation. Leaves are used to wrap foods in, strawberry stems are left attached and a mini plastic iris hovers in the background to provide color. And don’t forget that bento staple: plastic grass!

▼Sashimi has become an accepted, if not desirable, ingredient in funereal meals. Notice the foliage: an ornamental chrysanthemum and a shiso leaf (both edible) on top of shredded daikon radish.

- What should not be included in Ozen?

You won’t find sekihan (red beans and rice) in the departing meal because red (beans) and white (rice) is a celebratory color more suited to weddings. In a funeral, sometimes black beans and rice are used instead.

Mrs. Harada, a funeral bento-maker says the symbols of shochikubai (pine, bamboo and plum) should not be used because they are used for celebrations such as weddings and births. More often used in art as motifs on vases and china, you’ll also find the celebratory symbols gracing lacquer bento boxes for New Years. For funerals you’ll find the lotus blossom used as a motif instead, as it is not only serves as a symbol of Buddhism, but one of enlightenment.

- How much do Ozen cost?

By now you’re probably wondering how much these spreads cost and if it’s worth it to try to attend as many funerals as possible to get a good wholesome meal. But being a guest at a funeral in Japan is going to be set you back by 10,000 to 30,000 yen (US$84-253), depending on your relationship to the deceased. This money is presented to the family to help defray the costs of the ceremony. If you’re just an acquaintance, then you’ll pay as little as 5,000 yen (and probably not be invited to the actual funeral). If you are a neighbor, you may pay 10-20,000 yen (you decide), and close family pay 30,000 yen or more. So if you are of the latter two types of guests, your fees are going to help pay the costs of the funeral, which includes the meal.

Nonetheless, we were curious as to the cost of putting one of these meals together, so we visited a packaging store to find out.

The construction of Ozen starts with a tray with little decorative food domiciles in it.

▼The plastic trays are tastefully decorated using subdued colors with the dishes molded into it.

▼Here, we see them on the shelves at a packaging store that sells wholesale to bento makers.

▼The price on this one with seven compartments is sold in packs of 20 and costs 155.5 yen per tray.

▼ The trays, after they’re filled with food, are put into a box, like this one. The chopsticks are provided by the bento-maker and has their restaurant/company name printed on the chopsticks cover.

▼These boxes, or box covers, are bought separately. This is a packet of 50. Each one costs 41.5 yen.

To complete the set, the preparer must buy a furoshiki cloth wrapping (which will be explained later) and a nice tasselled elastic band to go around the box to keep it closed, another 100 yen or so per bento. While these combined costs are not too high (about 300 yen), since these are wholesale prices, it’s safe to say that the bento-maker will add an extra 500 yen (US$4.21) to the cost of the meal for putting the package together including labor. So that leaves us with the cost of the food and preparation. When I asked obento-makers the price, they generally agreed that Ozen starts at around 3,000 yen (US$25) for the most basic. The one we’ve featured in the photo is typical of one that costs 5,000 yen (US$42).

- Why are these meals so big?

A typical funeral bento box measures 38 cm x 28 cm and is about 6 cm in deep. While you may eat the whole box of food in one go, most people will eat some at the venue, then take the rest home. “Funerals are a stressful time for families and friends, so if they don’t have to cook afterwards, it will make things easier for them,” says Mrs. Harada. Most people will finish the meal that night for dinner or save some of it for the next day.

And this is where the furoshiki comes in. It is used to wrap the unfinished bento in.

▼Bento wrapped in a (disposable) furoshiki cloth by the guest.

The furoshiki makes the box easy to carry home on the train.

These boxes, by the way, can be thrown out on recycled garbage day and are stacked together at the neighborhood recycling spot.

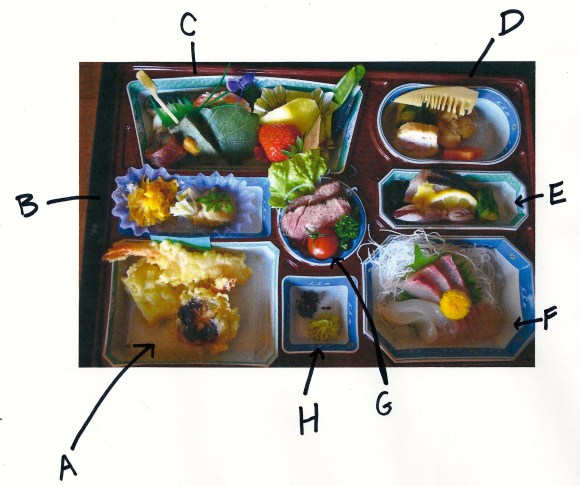

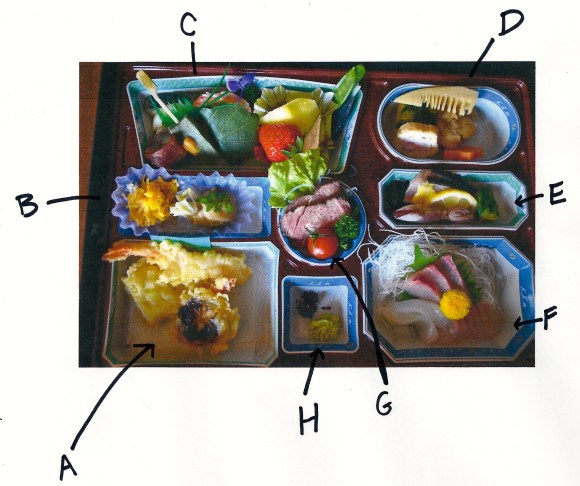

- A Closer look at Ozen ingredients:

Let’s enumerate the ingredients of this funeral bento. Note that this Ozen included rice, miso soup and chawanmushi, a savory egg custard not pictured as they were served separately in their own bowls. The meal was followed by green tea.

Clockwise from bottom left-hand corner:

A. Tempura. This tempura appears to be served rather sparingly. That’s not exactly true. This is an actual bento I received at a funeral and as I sat there staring at this gorgeous gastronomic wonder, I really wanted to take a photo of it. But this would be really impolite at a funeral, right? So I refrained and instead started eating the tempura. But as I tucked into the veggies, I noticed a 70-year-old woman at the next table using her smartphone–to take a photo! Of course, I immediately followed her example and took this photo. Unfortunately, half the tempura was already gone.

B. The small round paper pleated cup holds namasu: daikon radish cut into fine strips and seasoned with vinegar, with shredded omelet on top. The cup on the right is a shellfish topped with miso and mustard.

C. A strawberry and a piece of melon are in a foil cup on the right with two snow peas poised in the corner. Next to the strawberry is a rice cake wrapped in an oak leaf. Bamboo skewered wheat gluten flavored with macha. The round piece to the left of that is burdock rolled with sliced beef. Behind that, in back of the iris and bento grass, barely visible, is sliced lotus root seasoned with vinegar, a boiled shrimp and a baked Spanish mackerel. Also, next to the snow peas you’ll find a small plastic bottle of soy sauce.

D. bamboo shoot, boiled fish and a piece of broccoli. On the left in the front is fish paste mixed with vegetables and in the front on the right is a piece of carrot in the shape of a star.

E. Fresh baby squid in the front, lemon, Spanish mackerel sashimi with a dollop of miso for the boiled seaweed on the left. To the right is slices of cucumber soaked in vinegar.

F. For the main sashimi dish, we have squid and hamachi on top of a shiso leaf and a bed of shredded daikon radish and topped with a yellow chrysanthemum.

G. Two slices of roast beef, a lettuce leaf, parsley, and a mini tomato.

H. Two spices in this square container are tade in the back and wasabi in the front.

I suppose the best thing about this custom of eating Ozen and sharing it with the deceased is that there is no such thing as “the last supper.” And just a note that when I die, I’d like dessert too!

All images © Amy Chavez/RocketNews24

Japanese supermarket’s funeral ad sparks controversy, debate over “blasphemy”

Japanese supermarket’s funeral ad sparks controversy, debate over “blasphemy” Do-it-yourself funeral kits go on sale in Japan

Do-it-yourself funeral kits go on sale in Japan Three main reasons why fewer and fewer Japanese people are having funerals

Three main reasons why fewer and fewer Japanese people are having funerals Delicious bento without the plastic waste — the OniBen is the one-handed mini meal we all need

Delicious bento without the plastic waste — the OniBen is the one-handed mini meal we all need Insider tip leads us to one of the best obento lunchbox finds in Japan!

Insider tip leads us to one of the best obento lunchbox finds in Japan! Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it?

Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it? Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo

Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】

Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】 Hey, Japanese taxi driver! Take us to your favorite restaurant in Tsuruga City!

Hey, Japanese taxi driver! Take us to your favorite restaurant in Tsuruga City! We go looking for the free kaoyu hot spring facebath of onsen town Kusatsu【Photos】

We go looking for the free kaoyu hot spring facebath of onsen town Kusatsu【Photos】 Osaka’s creepy cute mascot speaks for first time, adds more fuel the creepy OR cute debate【Video】

Osaka’s creepy cute mascot speaks for first time, adds more fuel the creepy OR cute debate【Video】 Japanese black curry “experiment” takes place at an unlikely restaurant branch in Tokyo

Japanese black curry “experiment” takes place at an unlikely restaurant branch in Tokyo How to make an epic pizza at a Japanese family restaurant

How to make an epic pizza at a Japanese family restaurant A new meaty dawn for Akihabara as neighborhood’s best steak/hamburger steak restaurant reopens

A new meaty dawn for Akihabara as neighborhood’s best steak/hamburger steak restaurant reopens Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things New Studio Ghibli bedding sets are cool in all senses of the word

New Studio Ghibli bedding sets are cool in all senses of the word We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community

We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park

There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball

Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 Uniqlo opens its first Furugi Project secondhand clothing pop-up shop in Tokyo

Uniqlo opens its first Furugi Project secondhand clothing pop-up shop in Tokyo Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down

Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down Toyota built a life-sized Miraidon Pokémon and are letting people test drive it this weekend

Toyota built a life-sized Miraidon Pokémon and are letting people test drive it this weekend Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train

Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules

Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears?

Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears? New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure

Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure Yahoo! Shopping now offers funeral services in Japan

Yahoo! Shopping now offers funeral services in Japan We tried a gourmet chocolate bento box worth 2,700 yen, and every bite was worth it

We tried a gourmet chocolate bento box worth 2,700 yen, and every bite was worth it Increasing number of Japanese ditching traditional attitudes about weddings and funerals

Increasing number of Japanese ditching traditional attitudes about weddings and funerals Celebrate the New Year with a special and limited edition Barbie bento box of New Year foods

Celebrate the New Year with a special and limited edition Barbie bento box of New Year foods Cheap vs. expensive — Is a premium-priced tempura bento really worth it?【Taste test】

Cheap vs. expensive — Is a premium-priced tempura bento really worth it?【Taste test】 Secret lunch spot in Tokyo’s Muji Hotel is a hidden gem that few people know about

Secret lunch spot in Tokyo’s Muji Hotel is a hidden gem that few people know about Company PET partners with Kyoto temple to offer genuine funeral services for beloved pets

Company PET partners with Kyoto temple to offer genuine funeral services for beloved pets Japanese boxed lunches pulling into France at authentic bento stand opening in Paris station

Japanese boxed lunches pulling into France at authentic bento stand opening in Paris station Tokyo temple holds funeral for personal seals in effort to reform outdated business practice【Vid】

Tokyo temple holds funeral for personal seals in effort to reform outdated business practice【Vid】 We devour a three-kilogram spaghetti and meatballs obento lunchbox

We devour a three-kilogram spaghetti and meatballs obento lunchbox Japanese university’s amazing dining menu fills students’ bellies for a very reasonable price

Japanese university’s amazing dining menu fills students’ bellies for a very reasonable price Japan super budget dining – What’s the best way to spend 1,000 yen at Family Mart?

Japan super budget dining – What’s the best way to spend 1,000 yen at Family Mart? Meet the Mega Bento, a Japanese meal that’s heavier than a newborn baby

Meet the Mega Bento, a Japanese meal that’s heavier than a newborn baby Japan’s subscription service simply called “Mom” is totally worth it

Japan’s subscription service simply called “Mom” is totally worth it Millennium-old Japanese temple offering funeral service for broken record player needles

Millennium-old Japanese temple offering funeral service for broken record player needles

Leave a Reply