Wait, what? These weren’t in chapter one of Genki….

If you’ve studied Japanese, then chances are you’ve seen the voicing marks (tenten in Japanese) that go above some hiragana. You’ve also probably encountered the little circles (maru in Japanese) that go above the hiragana for ha, hi, fu, he, ho, turning them into pa, pi, pu, pe, po.

But something you might’ve never seen before is the little circles being used with other hiragana, namely ka, ki, ku, ke, ko.

▼ Everything I thought I knew about Japanese is a lie….

They may look a little strange to learners of Japanese. How would you even pronounce them? P-ha, p-hi, p-fu?

Nope! These weirdos represent voiced nasal sounds and are pronounced similar to: nga, ngi, ngu, nge, ngo.

▼ Skip to 0:30 in this video to have a nice man in a hat pronounce the difference between the normal ga, gi, gu, ge, go and nga, ngi, ngu, nge, ngo.

Okay, so that’s great and all, but where are these hiragana used? And if they’re so cool, why aren’t students of language ever taught them?

Good questions! These voiced nasal sounds are mostly exclusive to the Eastern dialect of Japan in the Kanto and Tohoku regions (Tokyo, Fukushima, Aomori, etc.). In the Western regions (Hiroshima, Kyushu, etc.), the voiced nasal sounds don’t exist, and they somehow get along just fine with only ga, gi, gu, ge, go.

Since Tokyo Japanese is considered “standard” Japanese, news anchors and announcers have to go through rigorous voice training programs to ensure that they’re giving the “correct” nasal touch to their voiced sounds.

So if you want to sound like a fancy Tokyo-ite, then here’s a handy guide to when your ga, gi, gu, ge, gos should turn into nga, ngi, ngu, nge, ngos:

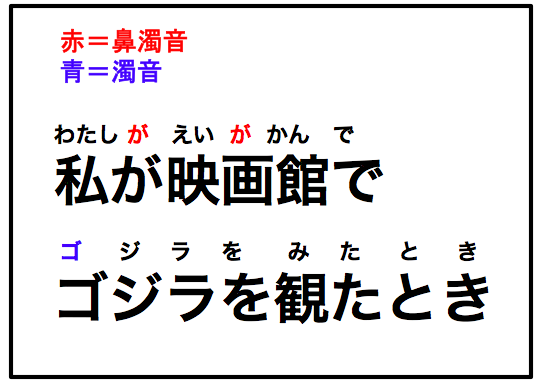

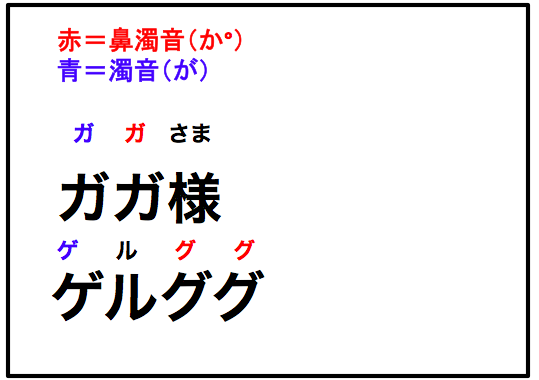

▼ Red represents the voiced nasal (ng),

and blue represent the normal voiced (g).

▼ The voiced nasal is used for the particle ga, and for every

ga, gi, gu, ge, go sound that doesn’t come at the beginning of a word.

Aside from those undergoing announcer training though, most Japanese people never encounter these bizarre-looking hiragana, and that’s why students of Japanese aren’t taught them.

It makes sense though; in the U.S., we don’t usually take dialect differences into account when spelling English either: “aunt” is spelled the same even in places that pronounce it as “ant,” and “soda” is spelled the same even in places that pronounce it as “pop.”

According to Japanese linguists, the voiced nasal has been slowly dying off, being replaced by the normal voiced sounds that we’re all familiar with. At this rate it might not be too much longer before they’re extinct sounds.

▼ Skip to 1:40 to see how the red circles (normal g) has been invading from the west to take over the green circles (nasal ng) over the past 50 years.

Personally I know that whenever I use the voiced nasals, I just feel like I sound pretentious, so I usually keep them hidden away in my nose. But what do you do when you speak Japanese? Were you taught to use the voiced nasals? If so, let loose with some in the comments, so we can preserve their nasal-y beauty for all eternity.

References: NHK Online, Notre Dame Seishin University

Images: ©RocketNews24

[ Read in Japanese ]

Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: A Tick on Titan 【Episode #3】

Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: A Tick on Titan 【Episode #3】 Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Fullmedal Alchemist 【Episode #5】

Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Fullmedal Alchemist 【Episode #5】 Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Dragon Bowl【Episode #4】

Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Dragon Bowl【Episode #4】 Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Death Vote 【Episode #6】

Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Death Vote 【Episode #6】 How do you pronounce “Among Us” in Japanese? Simple question has linguistically deep answer

How do you pronounce “Among Us” in Japanese? Simple question has linguistically deep answer Chance to play Teris on a massive staircase in Kyoto Station coming in March

Chance to play Teris on a massive staircase in Kyoto Station coming in March Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Lawson adds doughnuts to its convenience store sweets range, but are they good enough to go viral?

Lawson adds doughnuts to its convenience store sweets range, but are they good enough to go viral? The best Hobonichi diaries, covers and stationery for 2026

The best Hobonichi diaries, covers and stationery for 2026 Ramen for 99 yen?!? Best value-for-money noodles found at unlikely chain in Japan

Ramen for 99 yen?!? Best value-for-money noodles found at unlikely chain in Japan Ghibli Catbus keychain with rotating destination marker will make Totoro fans’ heads spin【Photos】

Ghibli Catbus keychain with rotating destination marker will make Totoro fans’ heads spin【Photos】 Family Mart makes new anti-food-waste stickers, free for other stores and restaurants to use too

Family Mart makes new anti-food-waste stickers, free for other stores and restaurants to use too We visited a “terrible” Japanese hot spring hotel near Narita Airport

We visited a “terrible” Japanese hot spring hotel near Narita Airport Australian mother reflects on “lunchbox shame” she felt from her son’s Tokyo preschool teacher

Australian mother reflects on “lunchbox shame” she felt from her son’s Tokyo preschool teacher Potama serves up epic rice balls like no other, and there’s only one store in Tokyo

Potama serves up epic rice balls like no other, and there’s only one store in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels

Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu”

The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu” The surprising reasons why some hiragana aren’t allowed to be used on Japanese license plates

The surprising reasons why some hiragana aren’t allowed to be used on Japanese license plates Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 2)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 2) Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1) Japanese writing system gets turned into handsome anime men with Hiragana Boys video game

Japanese writing system gets turned into handsome anime men with Hiragana Boys video game World’s first moaning hiragana character either a stroke of genius or just plain weird【Video】

World’s first moaning hiragana character either a stroke of genius or just plain weird【Video】 The top 10 hardest Japanese words to pronounce – which ones trip you up?【Video】

The top 10 hardest Japanese words to pronounce – which ones trip you up?【Video】 Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker

Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker Magazine teaches Japanese using Kemono Friends anime, Japanese netizens can’t stop laughing

Magazine teaches Japanese using Kemono Friends anime, Japanese netizens can’t stop laughing Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Narutoe 【Episode #2】

Learn Japanese through ridiculous manga: Narutoe 【Episode #2】 One simple kanji character in super-simple Japanese sentence has five different pronunciations

One simple kanji character in super-simple Japanese sentence has five different pronunciations The reason why Japanese students don’t pronounce English properly

The reason why Japanese students don’t pronounce English properly Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them

Seven mistakes foreigners make when speaking Japanese—and how to fix them Pronunciation anxiety: many Japanese people don’t want to speak English unless it’s “perfect”

Pronunciation anxiety: many Japanese people don’t want to speak English unless it’s “perfect” Let’s learn how to sing “Jingle Bells” in Japanese with the help of Santa Pikachu!【Video】

Let’s learn how to sing “Jingle Bells” in Japanese with the help of Santa Pikachu!【Video】 Japanese students despair over the many, MANY ways you can describe a dead flower

Japanese students despair over the many, MANY ways you can describe a dead flower