One simple chart could have made all the difference.

The average level of English capability in Japan is pretty low, despite the language being a required subject in schools starting from junior high. There are a number of possible reasons for this dichotomy, but Japanese Twitter user @Heehoo_kun has found what, for him, is the biggest.

英語でこれを教えないせいでどんだけ今まで無駄な時間を費やしてたのか pic.twitter.com/b6ihPbxoQf

— (っ╹◡╹c) (@Heehoo_kun) April 15, 2019

“We wasted so much time in English class,” tweeted @Heehoo_kun in exasperation, “because they didn’t teach us this.”

So what’s this missing piece of the English puzzle @Heehoo_kun says he was never given? Phonics. Specifically, he tweeted a page from a book showing a basic phonics pronunciation chart for each letter of the alphabet.

While phonics might seem like a practically self-explanatory concept to native English speakers, that’s often far from the case for Japanese learners of English, for a number of reasons. First off, in Japanese almost every consonant has to be connected to a vowel (aside from a small handful of exceptions like “n” and consonant blends “sh” and “ky,” and even the blends have to be followed immediately by a vowel). Because of that, there’s no indigenous Japanese concept that the letter b or t can have any sort of sound by itself.

▼ “What is the sound of one t existing?

The second problem is that in Japanese, even when using the phonetic scripts called hiragana and katakana, there’s no difference between the name of the character and the way it’s pronounced. For example, if you write “ramen” in Japanese, it’s ラーメン, and that first character, ラ, is both called and pronounced “ra.” Compare that to English, where the first letter in ramen, r, makes a “r-“ sound, but the name of the latter itself is pronounced like “ar.”

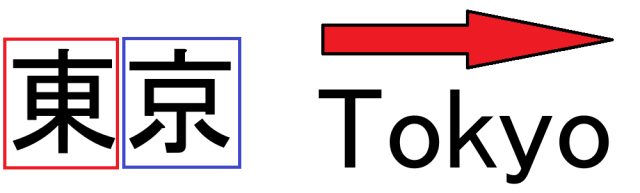

Combined, these two factors mean that when they’re reading Japanese, Japanese people largely string together pre-determined sets of characters, each of which they’ve already memorized the correct pronunciation for. Even when using non-phonetic kanji characters, words are made up of pre-set chunks, like with Tokyo, 東京, which a native Japanese reader’s brains parses by recognizing that 東 is “To” and 京 is “kyo.”

English, though, requires the complete opposite approach. The reader must stay patient and pronounce one letter at a time until the sounds eventually blend together to form the word. However, if teachers and texts don’t properly explain that, as seems to be what happened with @Heehoo_kun, English is going to feel like an arbitrary and intimidating mess of vocabulary words that have to be memorized in their entirety.

▼ Reading is a staccato process in Japanese, but a flowing one in English.

@Heehoo_kun says he found the phonics chart in a book from Japanese author Hiroshi Matsui titled One-Shot Understandable English Pronunciation for Japanese People (available on Amazon here), and a number of other Twitter users were equally impressed with its phonics chart, leaving comments such as:

“This is so true!!!!! When I was in the first year of junior high, I tried reading A, B, C, D as “ah, bu-, cu- du-,” and my teachers all told me I was wrong!!! My method was just too advanced for them.”

“I did the same thing, and my teacher got mad at me.”

“Schools don’t teach phonics because Japan is all about written tests for English.”

“I wanted a chart like that. I kept trying to tell my teacher I just couldn’t figure out how to read words in English, and this would have been such a big help.”

“I’m in high school now, and I don’t remember doing phonics in junior high.”

However, the quality of English instruction in Japan tends to vary widely depending on the specific instructor and institution, and a few other online commenters chimed in to say this wasn’t their first exposure to phonics.

“I think schools are required to teach this starting in junior high now.”

“They cover phonics in the English-learning programs on [public broadcaster] NHK.”

“I took after-school classes at an English conversation school starting in the third year of elementary school, and I learned phonics then.”

Still, @Heehoo_kun and others like him never got this critical English-learning tool, which is probably something important to keep in mind should you find yourself working in the English-teaching field in Japan, or otherwise trying to communicate with a Japanese person in English.

Source: Twitter/@Heehoo_kun via Jin

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: Pakutaso, SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he’s always up for some linguistics.

Pronunciation anxiety: many Japanese people don’t want to speak English unless it’s “perfect”

Pronunciation anxiety: many Japanese people don’t want to speak English unless it’s “perfect” English teachers in Japan apologize for having low-proficiency kids say “poison” in assigned video

English teachers in Japan apologize for having low-proficiency kids say “poison” in assigned video The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu”

The science behind why English speakers can’t pronounce the Japanese “fu” How do you pronounce “Among Us” in Japanese? Simple question has linguistically deep answer

How do you pronounce “Among Us” in Japanese? Simple question has linguistically deep answer Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura cherry blossom collection for hanami season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura cherry blossom collection for hanami season 2026 Sakura Festival in Chiyoda mixes illuminations, boats, music, and Rilakkuma in the heart of Tokyo

Sakura Festival in Chiyoda mixes illuminations, boats, music, and Rilakkuma in the heart of Tokyo Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now

Drift ice in Japan is a disappearing winter miracle you need to see now Kyoto raises hotel accommodation tax to fight overtourism, travelers could pay up to 10 times more

Kyoto raises hotel accommodation tax to fight overtourism, travelers could pay up to 10 times more Lawson adds doughnuts to its convenience store sweets range, but are they good enough to go viral?

Lawson adds doughnuts to its convenience store sweets range, but are they good enough to go viral? A visit to the best UFO catcher arcade in the universe!

A visit to the best UFO catcher arcade in the universe! What happens when you wear a smile mask on a Japanese train?

What happens when you wear a smile mask on a Japanese train? The best Hobonichi diaries, covers and stationery for 2026

The best Hobonichi diaries, covers and stationery for 2026 Viral Japanese cheesecake from Osaka has a lesser known rival called Aunt Wanda

Viral Japanese cheesecake from Osaka has a lesser known rival called Aunt Wanda Majority of Japanese women in survey regret marrying their husband, but that’s only half the story

Majority of Japanese women in survey regret marrying their husband, but that’s only half the story Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels

Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results

Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says The reason why Japanese students don’t pronounce English properly

The reason why Japanese students don’t pronounce English properly Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker

Japanese elementary school student teaches us all how to pronounce English like a native speaker Official Tokyo Marathon T-shirts get recalled for English spelling mistake

Official Tokyo Marathon T-shirts get recalled for English spelling mistake Four ways Japanese isn’t the hardest language to learn

Four ways Japanese isn’t the hardest language to learn English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect

English conversation school in Japan has clever reminder that students don’t have to be perfect English for otaku – New book provides fans with skills to internationalize their oshikatsu

English for otaku – New book provides fans with skills to internationalize their oshikatsu Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1) Iisjhaisha? Japan’s biggest English test sends out a baffling message

Iisjhaisha? Japan’s biggest English test sends out a baffling message Does Comiket need to revise its booth code system for foreigners who don’t understand Japanese?

Does Comiket need to revise its booth code system for foreigners who don’t understand Japanese? Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japanese student teased for American pronunciation gets sweet revenge on classmates

Japanese student teased for American pronunciation gets sweet revenge on classmates Ridiculous Japanese TV program says English pronunciation is to blame for coronavirus spread【Vid】

Ridiculous Japanese TV program says English pronunciation is to blame for coronavirus spread【Vid】 Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 Why Does Engrish Happen in Japan? 30-year-old fart-related signage mistake edition

Why Does Engrish Happen in Japan? 30-year-old fart-related signage mistake edition Top Japanese baby names for 2025 feature flowers, colors, and a first-time-ever favorite for girls

Top Japanese baby names for 2025 feature flowers, colors, and a first-time-ever favorite for girls