This underground fortress isn’t dubbed “Japan’s No. 1 Mole Station” for nothing.

Nestled in the mountains at the northernmost tip of Gunma Prefecture is a hot spring resort town called Minakami. While most people visit for the onsen hot springs, others come for the hidden gem deep below ground — an underground station called Doai.

Doai Station is a must-visit destination for train enthusiasts, as it’s known as “Japan’s No. 1 Mole Station“, due to the fact that it’s the deepest train station in the country. Here, passengers aren’t dissimilar to moles, in the sense that they have to make their way out of the deep dark depths and into the world at the top of the tunnel.

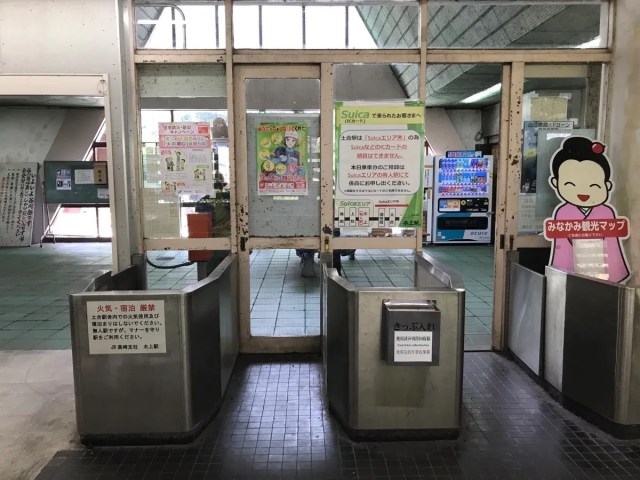

▼ Above ground, Doai (どあい) looks like an ordinary station, but inside it’s anything but.

To get here, our reporter Takamichi Furusawa hopped on a JR Joetsu Line train that connects Gunma and Niigata prefectures. Rollicking through the mountains, he gazed out at the countryside during the short journey, wondering what it would be like to live here.

Immersed in wanderlust, Takamichi arrived at the mysterious “unexplored station” a short while later, stepping off the train in a dark tunnel. A whole load of other passengers alighted here with him, so it was more lively than he expected.

Takamichi was visiting on a Sunday, which was probably why there were so many passengers at this time, and many of them appeared to be tourists like himself, with some posing by the station sign for a commemorative photo.

He was grateful for the company because it would be terrifying to be alone here. Looking down the train tracks, the concrete and lights made it feel like an underground fortress, and an an eerie atmosphere hung in the air.

Looking around, he began to feel a little nervous as he couldn’t find the platform for a train back to Tokyo, but then he remembered that this station has a very unusual design, with the underground platform here servicing Niigata-bound trains only. Passengers heading to Tokyo have to make their way to the platform above ground, where the Tokyo-bound trains operate.

▼ So he headed up to the Exit.

Up is the operative word here, as that’s the direction he found himself in for the next ten minutes. There are no escalators or elevators at this station — just stairs, and there are loooooaaads of them.

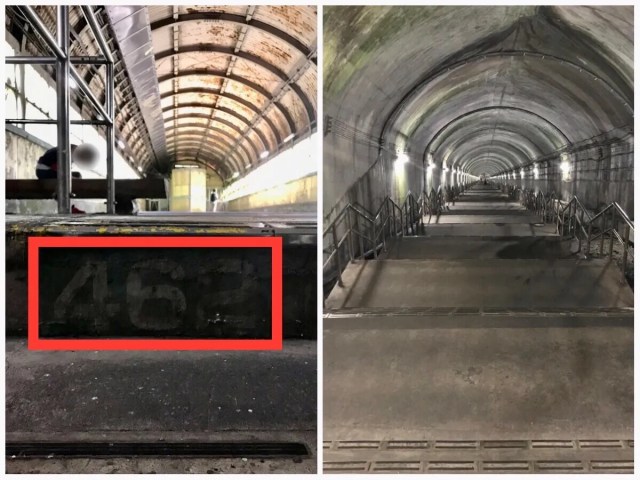

▼ Doai’s famous staircase.

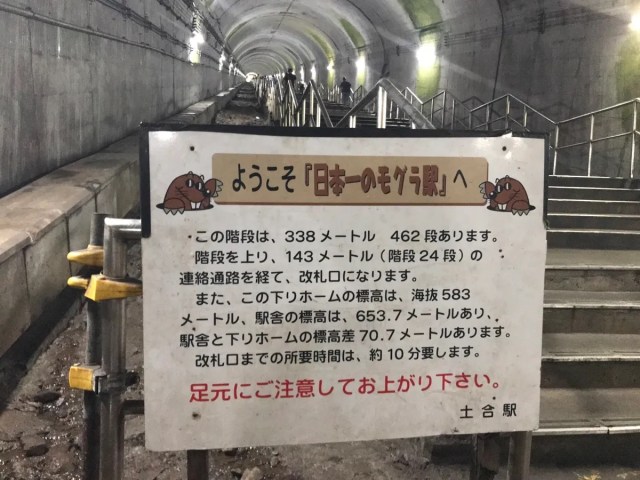

The signboard at the bottom of the stairs reads, “Welcome to Japan’s No. 1 Mole Station” with a couple of moles next to it.

According to the signboard, this staircase is a whopping 338 metres (0.2 miles) long, and contains 462 steps. The altitude of the underground platform is 583 metres above sea level, while the above-ground platform is 653.7 metres above sea level, making the difference in elevation between them 70.7 metres.

Peering at the tiny hole of light that was hundreds of metres away, Takamichi’s heart began to pound as he felt a tinge of anxiety, wondering if he would be able to make it safely up to the top. Putting one foot in front of the other, he began the journey, and was relieved to find there was a landing after every five steps, which helped to make the ascent easier.

▼ Some of the landings had bench seating as well, to allow people to stop and rest if needed.

At around the 200th step, Takamichi’s ears began to hurt due to the change in air pressure so he sat on one of the benches to allow his ears to adjust to the elevation. When he felt ready, he continued on the journey, and as he rose from the cool depths of the underground, the temperature began to rise, causing beads of sweat to form on his brow.

Looking at the side of the stairs, he could see space had been made for an escalator, but according to station operators there are no plans to install it as of yet.

At the 350th step, Takamichi was sweating and out of breath. He really wanted to stop for another break on a bench, but all the benches he came across were already full with people so he had no choice but to keep going until finally, finally….

▼ …he reached the top.

Looking down from where he came, he felt an immense sense of achievement, as if he’d climbed a mountain. Who would’ve thought that exiting a train station could be such an accomplishment?

After soaking in the afterglow on the 462nd step, Takamichi bid a fond farewell to the underground area and headed for the ticket gate exit. The passage ahead of him looked like something out of a video game, with rusted ceilings and an old wooden partition-like structure at the far end.

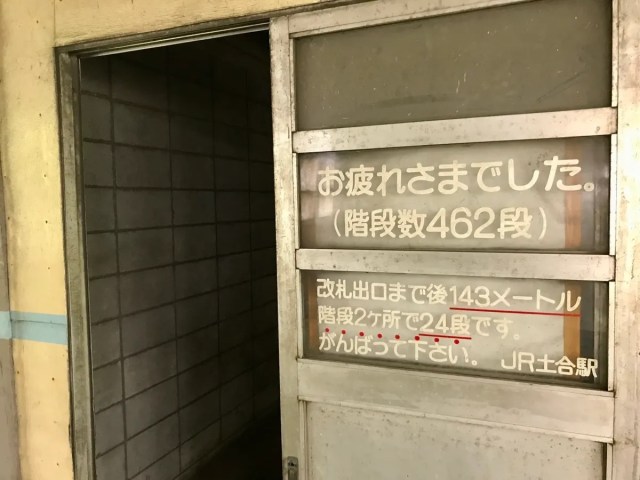

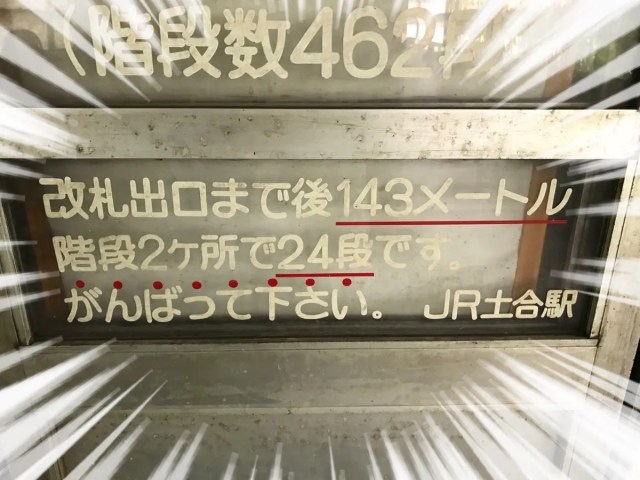

Walking around to the front of the wooden structure, he saw the adventure wasn’t over yet, as he now had to enter through this mysterious door. On the window, the kind words, “otsukaresama deshita” (“thank you for your hard work”) were printed, along with a message notifying passengers that this wasn’t the end of the journey.

The ticket gate itself is located another 143 metres from the top of the staircase he’d just climbed, and there are another 24 steps before you get there, bringing the total number of steps from platform to world above to 486.

Behind the door — the unusual structure is said to protect from wind gusts formed by passing trains — was a long passageway with moss-covered cement block walls. Takamichi continued along it, admiring the light as it shone through the windows, filtered by the trees outside.

The contrast between lightness and shade was beautiful, and Takamichi suddenly felt a kinship with the moles of the world as he prepared to emerge from the seemingly never-ending tunnel. The last part of the journey was beautiful and atmospheric, and it didn’t take long for him to climb the remaining steps and arrive at the ticket gates.

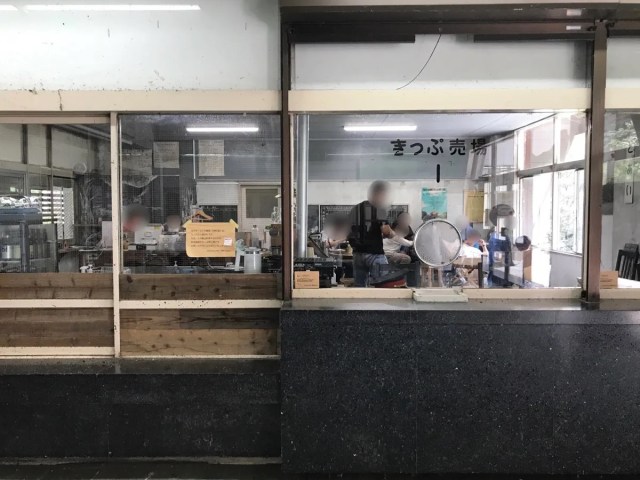

The ticket gates were a throwback to a bygone era, with absolutely no automation and no station staff overseeing them. While passengers with paper tickets can simply pop them in the ticket collection box, passengers like Takamichi, who’d tapped their Suica prepaid transport cards at the station they came from, have to adopt a different system.

According to the sign above, those travelling on a prepaid transport card need to declare their ride with staff at the next station they arrive at. The card won’t work again until the destination station has been manually registered and the amount deducted by staff, so if you’d like to avoid the hassle of having to approach staff and possibly wait in line, Takamichi recommends visitors to Doai buy a paper ticket instead.

If you’re travelling from Doai Station, you won’t be able to use your transport card as there are no automatic readers, so in that case you’ll want to use the machine near the ticket gate, where you’ll receive a “boarding station certificate” to show staff at your destination where you’ve come from.

▼ A station where paper tickets are more convenient than prepaid transport cards.

After exiting the station and climbing down the short flight of stairs above, Takamichi stopped to marvel at the building, which is designed to look like a mountain hut. Another unusual feature he noticed at the station was the fact that beer is being aged at the underground platform, due to its year-round cool temperatures.

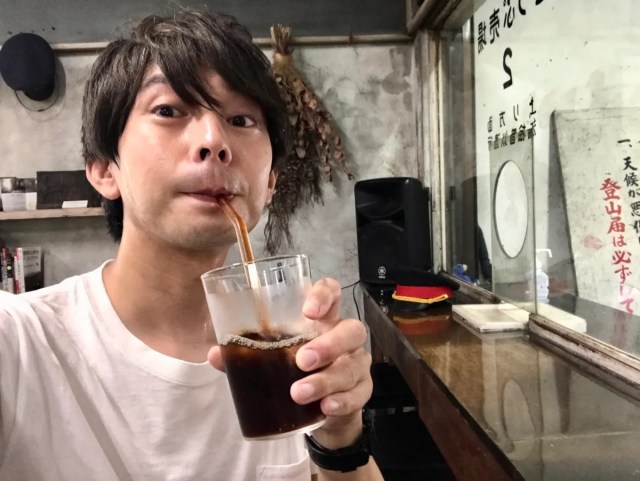

While the beer isn’t sold here, tea and coffees are, as the former station office and ticket booth have been renovated into a cafe.

Takamichi stopped to reward himself for his efforts with an iced coffee at the ticket counter, and it was one of the best he’s ever tasted.

After relaxing at the rural station for a while, it was time to board the train home. Heading to the above-ground platform, he was surprised at how different the atmosphere was here — sunny, bright and surrounded by nature, it was completely different to the dark, cold, concrete dungeon below.

As he slid into a seat on the train to enjoy the journey home, Takamichi felt a strange sense of accomplishment, similar to the feeling you get after clearing a dungeon in a video game. He’d explored the basement, climbed up the stairs in search of the exit, and walked through what appeared to be a hidden passage, giving him all the thrill and excitement of a game, but in real life.

If you’d like to experience an RPG dungeon in real-life, Doai Station will tick all your boxes. While you can explore the labyrinthine underground at Shibuya and Shinjuku stations in the heart of Tokyo, nothing beats the thrill of a dimly lit underground tunnel deep in the mountainous countryside, where trains always seem much more magical.

Related: Minakami Town Tourism Association

Images © SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

A video visit to Doai, one of Japan’s most terrifying train stations【Video】

A video visit to Doai, one of Japan’s most terrifying train stations【Video】 Japanese train becomes a restaurant at this sleepy countryside station

Japanese train becomes a restaurant at this sleepy countryside station Secret stairs at Tokyo Station dungeon come with a serious warning

Secret stairs at Tokyo Station dungeon come with a serious warning What’s up with the secret basement at this Japanese train station?

What’s up with the secret basement at this Japanese train station? Man stops train from leaving station in Japan, video goes viral online

Man stops train from leaving station in Japan, video goes viral online The results are in! One Piece World Top 100 characters chosen in global poll

The results are in! One Piece World Top 100 characters chosen in global poll Chance to play Teris on a massive staircase in Kyoto Station coming in March

Chance to play Teris on a massive staircase in Kyoto Station coming in March Tokyo street sweets: The must-snack treats of Nakano’s Refutei

Tokyo street sweets: The must-snack treats of Nakano’s Refutei McDonald’s Japan is now adding to my giant pile of home delivery junk mail

McDonald’s Japan is now adding to my giant pile of home delivery junk mail Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag

Eevee returns to Japan’s famous Tokyo Banana, bundled with a cute tote bag Pokémon Tokyo Banana’s latest offering is adorable Pikachu and Eevee chocolate cookie sandwiches

Pokémon Tokyo Banana’s latest offering is adorable Pikachu and Eevee chocolate cookie sandwiches Death Spray from Japan causes buzz online for powerful ability to cut ties with bad energy

Death Spray from Japan causes buzz online for powerful ability to cut ties with bad energy “Hey, Japanese taxi driver, take us to the best seafood restaurant in Noboribetsu!”

“Hey, Japanese taxi driver, take us to the best seafood restaurant in Noboribetsu!” Hello Kitty turns scary and cosplays as Japanese horror character – but still manages to be cute!

Hello Kitty turns scary and cosplays as Japanese horror character – but still manages to be cute! Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels

Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Train otaku say this is the narrowest train station platform in Japan

Train otaku say this is the narrowest train station platform in Japan Japanese train station stirs up nostalgia with beautiful rural setting and one-carriage train

Japanese train station stirs up nostalgia with beautiful rural setting and one-carriage train This unstaffed Japanese train station is like a Ghibli anime come to life

This unstaffed Japanese train station is like a Ghibli anime come to life Empty Tokyo train stations look like video game dungeons 【Photos】

Empty Tokyo train stations look like video game dungeons 【Photos】 Is it a Lawson or a train station? We investigate the mysterious Sekiguchi Station

Is it a Lawson or a train station? We investigate the mysterious Sekiguchi Station The Japanese train station where staff bow to departing passengers

The Japanese train station where staff bow to departing passengers Japanese train drivers caught performing cute in-sync movements at the station 【Video】

Japanese train drivers caught performing cute in-sync movements at the station 【Video】 Tokyo farewells Japan’s only double-decker Shinkansen with a special escalator at the station

Tokyo farewells Japan’s only double-decker Shinkansen with a special escalator at the station Chikan molester runs away from Japanese schoolgirls at train station in Japan【Video】

Chikan molester runs away from Japanese schoolgirls at train station in Japan【Video】 “Miyako” – one of the most beautiful, feels-inducing Japan videos you’ll ever see【Video】

“Miyako” – one of the most beautiful, feels-inducing Japan videos you’ll ever see【Video】 The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there

The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there New Japanese train station has no entrance or exit, only used to admire the scenery

New Japanese train station has no entrance or exit, only used to admire the scenery My Neighbour Totoro train jingles now playing at Tokorozawa Station【Videos】

My Neighbour Totoro train jingles now playing at Tokorozawa Station【Videos】 Shinkansen breaks down, causes all-day commuter chaos at Tokyo Station

Shinkansen breaks down, causes all-day commuter chaos at Tokyo Station A visit to Japan’s train station that looks like a spaceport in the middle of nowhere【Photos】

A visit to Japan’s train station that looks like a spaceport in the middle of nowhere【Photos】