We’re back and ready to take on the third, and most puzzling, type of Japanese text: katakana.

Recently, we started taking a look at the question of why the Japanese language needs three sets of written characters. To recap, we saw that kanji (complex characters that originated in China) are used to symbolize a term or concept, while hiragana (simpler, indigenous Japanese characters) represent sounds and provide extra context and grammatical information.

What we haven’t talked about yet is why Japanese needs two sets of phonetic script. Aside from hiragana, there’s also katakana, yet another group of 46 low-stroke-count characters used for writing things phonetically. Specifically, katakana get used for writing foreign loanwords.

But wait. We don’t need a whole new set of letters to write foreign loanwords in English. What makes things different in Japanese? Let’s dive into the answer, and since it’s going to take a while to explain, go ahead and pour yourself a cup of coffee.

▼ Which, incidentally, is written with katakana as コーヒー.

As mentioned last time, there are two huge advantages to using a mix of kanji and hiragana. There’s an extremely limited number of sounds available in the Japanese language, which results in many Japanese words having the same pronunciation but wildly different meanings, but the conceptual meanings kanji possess help to avoid confusion. Second, since Japanese is written with no spaces between words, using kanji for vocabulary and kana for grammar (to put things in broad terms) makes it easy to see the components of a sentence.

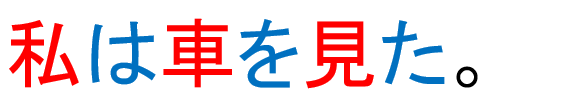

▼ Watashi ha kuruma wo mita or “I saw the car,” with kanji (i.e. vocabulary) written in red and hiragana (i.e. grammar) in blue.

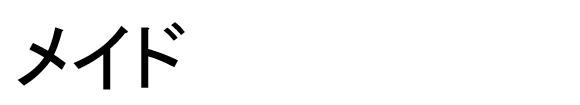

But that limited number of sounds means most foreign words can’t be properly rendered in written Japanese, which threatens to give the language even more homonyms. For example, let’s say we wanted to talk about a maid, of the maid cafe variety. Since Japanese syllables can’t end in a “D” sound, “maid” becomes meido (pronounced close to “maid-o”).

If we want to write meido in Japanese, it seems like the obvious thing to do is to write it in simple, phonetic hiragana. Technically we could do that, and it would look like this:

But this would make things confusing once we combined it with other words. Since hiragana is most commonly used for grammatical modifications, using it for a whole noun like “maid” can make it hard to see the breakdown of ideas in a sentence. Remember how easy it was to spot the breaks in “Watashi ha kuruma wo mita/I saw the car?” Look what happens when we replace the kanji for kuruma/car, 車, with meido, written all in hiragana (once again with kanji in red and hiragana in blue), to try to write Watashi ha meido wo mita/I saw the maid.

Now we’ve got that whole はめいどを cluster of hiragana, which makes it confusing to figure out where to draw the lines to separate the different ideas in the sentence. The は, めいど, and を are all serving different purposes, but because they’re in a singular mass of hiragana, it becomes difficult to differentiate one from the other. As a matter of fact, it can actually be somewhat confusing and cumbersome for Japanese adults to read young children’s storybooks if they’re predominantly written in hiragana without severely slowing down their reading speed so they can pick things apart.

OK, so now we’ve seen that using hiragana to write meido would be a bad plan. So how about writing it in kanji? The problem with that approach is that it raises the question of how, and more importantly when, to decide what the kanji for meido should be. There isn’t a starkly defined point at which vocabulary crosses over into other languages. Just look at the gradual manner in which “anime,” “otaku,” and “moe” have seeped into English.

In order to write everything in kanji, you’d need some sort of linguistic authority group constantly scanning for foreign words and developing new kanji for them before anyone in Japan has a need to write them. Even if such a framework existed, there’s the problem that if you chose the kanji based on how they’re pronounced, in an attempt to stay close to the original pronunciation of the loanword, the meaning of those individual kanji is going to be something completely different from that of the loanword they’re supposed to be representing.

▼ It’d be sort of like if I told you this picture represents a maid, and not approval, because “may” sounds similar to “maid.”

So now hiragana and kanji are both out. Using either for meido would both create new problems, and there’s no practical way to produce a universally accepted kanji for it either, so there needs to be another phonetic character set for writing foreign loanwords: katakana.

Which is why meido gets written in katakana like this:

Now armed with all three sets of characters, let’s go back and write Watashi ha medio wo mita again.

▼ Kanji in red, hiragana in blue, katakana in green

Now we’ve got a nice kanji-hiragana-katakana-hiragana-kanji-hiragana pattern, giving us the easy-to-spot breakdown of:

1. 私は: Watashi (I) and ha (the subject marker)

2. メイドを: meido (the maid) and wo (the object marker)

3. 見た: mi- (the verb see) and -ta (marking the verb as past tense)

Looking at the situation from the standpoint of how a language advances and evolves, katakana gives Japanese a way to quickly incorporate new concepts from other cultures with a non-kanji-based writing system. Without katakana, there’d be no way for Japan to efficiently add global ideas to its writing. Without hiragana, there’d be no way to easily modify grammar. And without either, you’d end up with basically the Chinese writing system, which makes the Japanese one look like a cakewalk in terms of difficulty for foreign learners.

Speaking of foreign learners, the existence of katakana actually works out in your favor, once you get the hang of some of the more common ways the pronunciation of foreign words gets corrupted in Japanese. Once again, say you’re reading the sentence Watashi ha meido wo mita/I saw the maid.

Even if you didn’t already know that meido is the Japanese word for “maid,” once you see that it’s written in katakana, you know it’s a foreign loanword. When you spot メイド, even if you’ve never seen the word used in Japanese before, you can ask yourself “Is there a word in English/French/Spanish/etc. that sounds like this?” and you’ve got a chance of deciphering the meaning on the spot.

Yes, until you get a little experience with the language and build up a base of vocabulary, sometimes it’s going to be extremely frustrating that Japanese has three different styles of writing. It didn’t all start making sense to me until a couple of months into studying the language, but one day it clicked, and in the roughly 20 years since I haven’t reversed my stance on it. Trust me, as weird as it might seem in the beginning, I’ve never met anyone for whom the relationship between kanji, hiragana, and katakana was the insurmountable stumbling block that kept them from becoming proficient in Japanese, so if that’s your goal, stick with it (and all three of them).

Got a burning question about Japanese? Ask Casey on Twitter! Got a question about any other kind of burning? Ask your doctor!

Top image: RocketNews24, Pakutaso (edited by RocketNews24)

Insert images: Pakutaso (1, 2), RocketNews24, Pakutaso (2)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1) Why are some types of Japanese rice written with completely different types of Japanese writing?

Why are some types of Japanese rice written with completely different types of Japanese writing? How to tell Japanese’s two most confusing, nearly identical characters apart from each other

How to tell Japanese’s two most confusing, nearly identical characters apart from each other Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character

Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character What does a kanji with 12 “kuchi” radicals mean? A look at weird, forgotten Japanese characters

What does a kanji with 12 “kuchi” radicals mean? A look at weird, forgotten Japanese characters Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism”

Osaka establishes first designated smoking area in Dotonbori canal district to fight “overtourism” 566 million yen in gold bars donated to Japanese city’s water bureau

566 million yen in gold bars donated to Japanese city’s water bureau Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Japanese bonsai trees made from paper stay beautiful without water or pruning

Japanese bonsai trees made from paper stay beautiful without water or pruning We tried all seven of Muji’s new “Bento of the Day” boxed lunch sets

We tried all seven of Muji’s new “Bento of the Day” boxed lunch sets Hey, 2020s kids! The ’90s have a sticker picture message waiting for you in Tokyo

Hey, 2020s kids! The ’90s have a sticker picture message waiting for you in Tokyo Shizuoka hot springs town invites you to see one of the longest hina doll displays in Japan

Shizuoka hot springs town invites you to see one of the longest hina doll displays in Japan We try out the upcoming R2-D2 virtual keyboard projector!

We try out the upcoming R2-D2 virtual keyboard projector! Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens

Now is the time to visit one of Tokyo’s best off-the-beaten-path plum blossom gardens Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】

Archfiend Hello Kitty appears as Sanrio launches new team-up with Yu-Gi-Oh【Pics】 Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning looks to be affecting tourist crowds on Miyajima

China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning looks to be affecting tourist crowds on Miyajima Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says One simple kanji character in super-simple Japanese sentence has five different pronunciations

One simple kanji character in super-simple Japanese sentence has five different pronunciations Why is the Japanese kanji for “four” so frustratingly weird?

Why is the Japanese kanji for “four” so frustratingly weird? Brain Gymnastics Quiz: Move one matchstick to create the name of a Japanese Prefecture

Brain Gymnastics Quiz: Move one matchstick to create the name of a Japanese Prefecture Japanese writing system gets turned into handsome anime men with Hiragana Boys video game

Japanese writing system gets turned into handsome anime men with Hiragana Boys video game German linguist living in Japan says kanji characters used for Germany are discriminatory

German linguist living in Japan says kanji characters used for Germany are discriminatory Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita

Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita Video of each Japanese hiragana getting “measured up” is oddly cute and satisfying【Video】

Video of each Japanese hiragana getting “measured up” is oddly cute and satisfying【Video】 Japanese park’s English dog turd warning minces no words【Why does Engrish happen?】

Japanese park’s English dog turd warning minces no words【Why does Engrish happen?】 Clever font sneaks pronunciation guide for English speakers into Japanese katakana characters

Clever font sneaks pronunciation guide for English speakers into Japanese katakana characters Yahoo! Japan finds most alphabetic and katakana words Japanese people want to find out about

Yahoo! Japan finds most alphabetic and katakana words Japanese people want to find out about How to write “sakura” in Japanese (and why it’s written that way)

How to write “sakura” in Japanese (and why it’s written that way) Twitter users say Japanese Prime Minister’s name is hiding in the kanji for Japan’s new era name

Twitter users say Japanese Prime Minister’s name is hiding in the kanji for Japan’s new era name Japanese first grader wins math contest by quantifying “which hiragana are the hardest to write”

Japanese first grader wins math contest by quantifying “which hiragana are the hardest to write” The extremely violent backstory of how to write the word “take” in Japanese

The extremely violent backstory of how to write the word “take” in Japanese Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video

Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video