Our spoiler-free review of Hayao Miyazaki’s first new film in five years comes with a sneak-peek look at the official movie programme.

Late last year, Japan’s national broadcaster NHK screened a documentary about Studio Ghibli’s co-founder and acclaimed director Hayao Miyazaki, revealing that he was working on his first film in five years, which would be an anime short screened exclusively at the Ghibli Museum in the Tokyo city of Mitaka.

Ever since the announcement, we’d been counting down the days until the movie’s first screening on 21 March, and after securing a ticket to one of the very first showings, it was time to head down to the museum’s in-house Saturn Theatre, the only place in the world where the much-hyped Kemushi no Boro, or Boro the Caterpillar, is being shown.

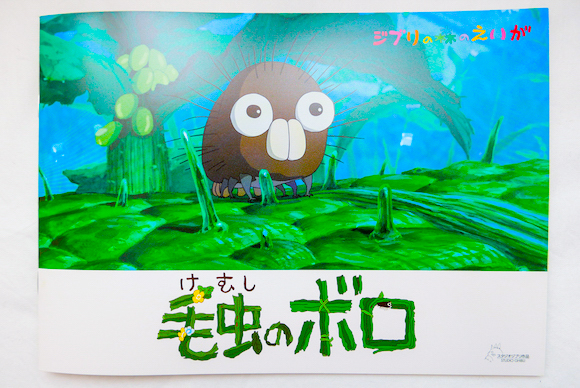

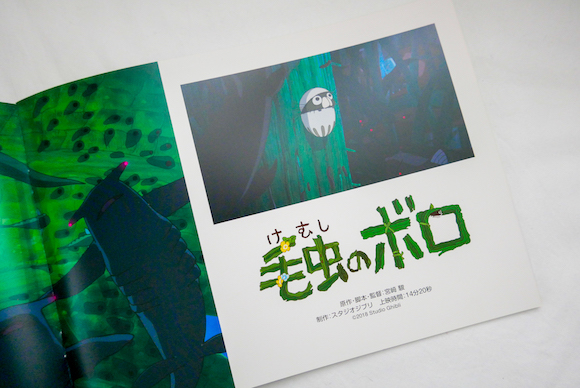

▼ Say hello to Boro the caterpillar.

Before viewing the film, we had a vague idea of what to expect, given all the media updates surrounding the new work in the lead-up to its release. Miyazaki himself, who’d been planning the story for almost 20 years, has described the short as “a story of a tiny, hairy caterpillar, so tiny that it may be easily squished between your fingers”, and just days ago it was revealed that famous Japanese comedian Tamori had lent his voice to the sound effects of the film.

Still, despite all this background information, nothing could’ve prepared us for what we saw – and heard – during the short anime’s 14-minute-20-second screening. Without giving away any major plot points or spoilers, there’s still a lot that can be said about this movie, particularly given that it’s an original screenplay, written and directed by the famously talented Miyazaki while he was meant to be retired from filmmaking.

So is Boro the Caterpillar set to be one of the best original shorts ever shown at the Ghibli Museum? Or will it end up being viewed as a self-indulgent post-retirement project that failed to hit the mark? Well, in our opinion, it might very well find itself slotting somewhere in between the two, and here’s why.

The film opens with Boro the Caterpillar hatching from an egg on a stalk of grass, surrounded by a new and unfamiliar environment, which he immediately sets out to explore. From the very beginning, the tone is strangely dark and unsettling, which works well to transport the audience into the 16-legged body of Boro, from where we can view the giant world through his tiny eyes, but at the same time, it’s a departure from many of the gentler, more child-friendly Ghibli shorts shown at the museum.

The first thing viewers are bound to notice, aside from the visuals, is the audio soundtrack. Miyazaki has been quoted as saying, “This film would not have been completed without Tamori-san”, and that’s entirely true, as his voice is used to bring sound to everything, from the titular caterpillar himself, to other flying insects, and even the sound of a girl’s squeaky tricycle.

To be honest, though, it’s an odd choice to use the voice of a 72-year-old male actor to bring life to the just-born baby character of Boro, and it’s even more peculiar to have this one actor create sounds, at a similar low pitch, for all the characters that appear in the movie. This makes it difficult for the viewers to distinguish Boro’s noises, and therefore connect to his emotional responses, in amongst all the other insects when they’re pictured together onscreen.

What’s even more surprising is the absence of any range in volume level; whether an insect is pictured close-up or buzzing further away in the distance makes no difference to its volume. While some might argue that this one-dimensional sound is due to the lack of a high-quality stereo system in the theatre – and it must be, because this is the work of an acclaimed animation studio and not an amateur college project – others might say that a different approach, perhaps with more range in volume and tone, would make it easier for audiences to get a feel for the different insect characters and add to the overall enjoyment of the film.

Miyazaki’s 2013 feature-length anime, The Wind Rises, was well-known for featuring mouth-made sound effects, but this short film takes this concept to a whole other level entirely. There’s very little range in tone here, and little effort made towards achieving any sense of realism. Whether he’s voicing the baby character of Boro, the caterpillar’s older senpai senior figures, or even a passing bumblebee, Tamori’s deep voice is neither light nor feminine, which means that all the insects in the film appear to be male.

Still, Tamori does an admirable job of making insects sound more like vehicles, jackhammers, and passing traffic rather than real insects, which makes us consider our own lives and the noisy environments we live in, and one of his best performances comes with the appearance of a hunting wasp, which Miyazaki has drawn to appear like an “aircraft on a battlefield”.

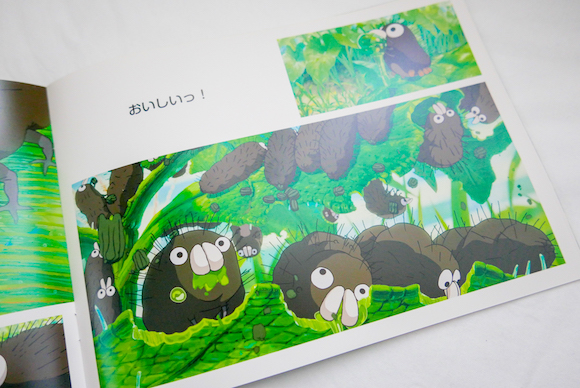

What the audio lacks in variety, the visuals make up for in spades, with beautifully drawn scenes capturing the moment Boro gets his first taste of “air jelly”, comes into contact with the sun’s rays, and munches on deliciously green nutrient-rich leaves.

Miyazaki has always been a masterful visual storyteller, needing nothing more than an image to evoke a mood, with even the tiniest of movements helping to convey an emotion. If you’ve ever seen Miyazaki’s 2006 short Mizugumo Monmon (The Water Spider) at the Ghibli Museum, you’ll see some common similarities in Boro the Caterpillar, both in imagery and storyline.

Water spiders and caterpillars are both tiny beings in large and often frightening environments, yet nothing in life remains constant, and both characters go on a journey of self-discovery, where they learn to adapt to new worlds and experiences. In this sense, Boro is a metaphor for our own lives, as seen through the eyes of a caterpillar, only without the pleasant sound effects and majestic soundtrack that featured in The Water Spider.

In fact, in Boro, even the incidental noises made by natural movements – like caterpillars pooping, which takes up a good portion of screentime – are all silent. This absence of real-world noise throughout the film, with cars, buses, and even the footsteps of humans left silent as Boro makes his journey through life, is a puzzling, pared-back move you’d expect to encounter in an arthouse film by an avante-garde director.

Watching the movie turns out to be like viewing the world from an inch below water, where you can see things going on around you, but all you can hear is your own voice in your head.

Is Miyazaki trying to tell us that caterpillars are hard of hearing? Or that we need to listen harder to the subtle noises in the natural environment around us? It’s an interesting and thought-provoking approach to filmmaking, and one which could probably only have been made by Miyazaki at this point in his career, when he has nothing to prove to anyone and can make stylistic choices that his producer friend Toshio Suzuki would have resisted years ago. After all, it was Suzuki who advised Miyazaki to put Boro on the backburner and go ahead with Princess Mononoke instead, when Miyazaki first pitched the film to him 20 years ago.

While viewers will be divided over Boro’s soundtrack, there’s no denying that Miyazaki has achieved what he set out to achieve with this new film. By viewing the world through the eyes of a tiny caterpillar with the use of stunning visuals, we are encouraged to re-evaluate our own lives and the way we live them.

While the soundtrack might be less grandiose than those of his other movies, by reminding us of the natural world around us, and the characters that live within it, Miyazaki’s legacy of promoting an environmentally aware lifestyle has never been louder or clearer. Sure, it’s a self-indulgent project that ties up unfinished business from the start of his career, but at the same time, it’s pretty wonderful in its unique style too.

Photos ©2018 Studio Ghibli © SoraNews24

New Hayao Miyazaki anime for Tokyo’s Ghibli Museum has spring debut date announced

New Hayao Miyazaki anime for Tokyo’s Ghibli Museum has spring debut date announced Miyazaki’s new animated short Boro the Caterpillar completed, voice actor revealed

Miyazaki’s new animated short Boro the Caterpillar completed, voice actor revealed Ghibli Museum merchandise from Boro The Caterpillar short anime movie now on sale!

Ghibli Museum merchandise from Boro The Caterpillar short anime movie now on sale! Studio Ghibli producer dishes the dirt on Hayao Miyazaki, Your Name, and their next big project

Studio Ghibli producer dishes the dirt on Hayao Miyazaki, Your Name, and their next big project The Place Where Totoro Was Born: New Studio Ghibli book includes art by Hayao Miyazaki’s wife

The Place Where Totoro Was Born: New Studio Ghibli book includes art by Hayao Miyazaki’s wife McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there

The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there Arrest proves a common Japanese saying about apologies and police

Arrest proves a common Japanese saying about apologies and police Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Our reporter takes her 71-year-old mother to a visual kei concert for the first time

Our reporter takes her 71-year-old mother to a visual kei concert for the first time Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it?

Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it? Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】

Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】 We tried Japan’s Strawberry Daifuku? liqueur, one of three dessert-themed liqueurs

We tried Japan’s Strawberry Daifuku? liqueur, one of three dessert-themed liqueurs Starbucks Japan’s new sakura collection arrives in stores for hanami season 2023

Starbucks Japan’s new sakura collection arrives in stores for hanami season 2023 Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community

We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park

There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park New Studio Ghibli bedding sets are cool in all senses of the word

New Studio Ghibli bedding sets are cool in all senses of the word Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball

Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball Hanton rice — a delicious regional food even most Japanese people don’t know about, but more should

Hanton rice — a delicious regional food even most Japanese people don’t know about, but more should New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Hamburg and Hamburg Shibuya: A Japanese restaurant you need to put on your Tokyo itinerary

Hamburg and Hamburg Shibuya: A Japanese restaurant you need to put on your Tokyo itinerary Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down

Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train

Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules

Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears?

Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears? New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty Kyoto creates new for-tourist buses to address overtourism with higher prices, faster rides

Kyoto creates new for-tourist buses to address overtourism with higher prices, faster rides Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure

Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure Hayao Miyazaki Working on Proposed New Anime Feature Film

Hayao Miyazaki Working on Proposed New Anime Feature Film Ghibli reveals genre of Hayao Miyazaki’s next anime, and that it’s also working on new CG film

Ghibli reveals genre of Hayao Miyazaki’s next anime, and that it’s also working on new CG film Hayao Miyazaki is getting worried about how his new anime is being marketed, Ghibli producer says

Hayao Miyazaki is getting worried about how his new anime is being marketed, Ghibli producer says Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno wants to make a live-action Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno wants to make a live-action Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind Pop-up “Very Hungry Caterpillar” cafe now open in Tokyo, very hungry fans rejoice

Pop-up “Very Hungry Caterpillar” cafe now open in Tokyo, very hungry fans rejoice Ghibli’s Boy and the Heron wins Academy Award, studio COO apologizes for Hayao Miyazaki’s absence

Ghibli’s Boy and the Heron wins Academy Award, studio COO apologizes for Hayao Miyazaki’s absence Our take on Studio Ghibli’s newest anime, When Marnie Was There【Impressions】

Our take on Studio Ghibli’s newest anime, When Marnie Was There【Impressions】 Ghibli’s The Boy and the Heron won a Golden Globe. Now can it win an Oscar?

Ghibli’s The Boy and the Heron won a Golden Globe. Now can it win an Oscar? Hayao Miyazaki sketches cute characters for new signboard at the Ghibli Museum【Video】

Hayao Miyazaki sketches cute characters for new signboard at the Ghibli Museum【Video】 Hayao Miyazaki appears at Ghibli Park…or does he?

Hayao Miyazaki appears at Ghibli Park…or does he? Ghibli Park: Opening date, first photos, and a new promo video produced by Studio Ghibli!

Ghibli Park: Opening date, first photos, and a new promo video produced by Studio Ghibli! Producer clarifies Studio Ghibli’s future, mentions that Miyazaki “would like to make an anime”

Producer clarifies Studio Ghibli’s future, mentions that Miyazaki “would like to make an anime” Miyazaki Blu-ray collection to be released with special bonus content but won’t come cheap!

Miyazaki Blu-ray collection to be released with special bonus content but won’t come cheap! Hayao Miyazaki speaks out against relocation of Okinawa U.S. base, criticizes Prime Minister Abe

Hayao Miyazaki speaks out against relocation of Okinawa U.S. base, criticizes Prime Minister Abe Video documentary explores the Essence of Humanity in the film works of Hayao Miyazaki【Video】

Video documentary explores the Essence of Humanity in the film works of Hayao Miyazaki【Video】

Leave a Reply