But a potential problem is lurking in its proposed revision.

The Genetics Society of Japan, as you might expect, spends a lot of time discussing dominant and recessive genes. That doesn’t mean its members like those terms, though, and the organization has announced that it will no longer be using the traditional Japanese terms for “dominant” and “recessive,” citing a need to replace them in order to prevent misunderstandings about, and prejudice against, those in the latter group.

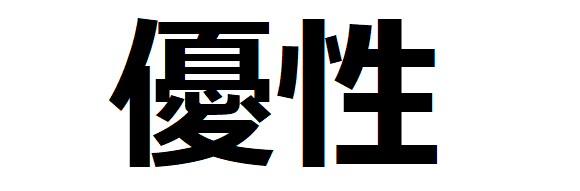

In Japanese, the word for dominant is yusei, which is written in kanji like this.

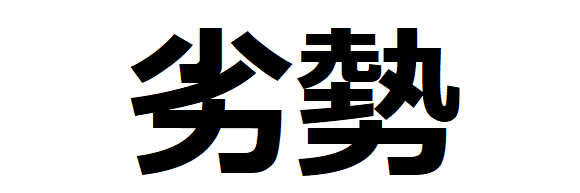

Recessive, on the other hand, is ressei, and written with these characters.

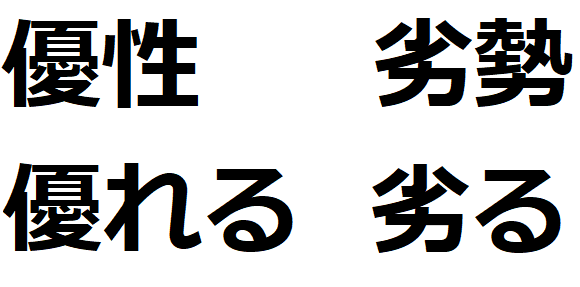

The problem with these terms, according to the GSJ, lies in the other vocabulary their respective first kanji show up in. 優 is the leading character in the verb sugureru (優れる), which means “to be better/superior/preferable.” Meanwhile, 劣 is found at the beginning of otoro (劣る), a verb that’s the opposite of sugureru and means “to be inferior.”

▼ Dominant and superior (left column) vs. recessive and inferior (right)

The GSJ contends that because of these overlapping kanji, laymen can become confused and arrive at the incorrect conclusion that dominant genes or genetic traits are preferable to recessive ones, and thus view people with recessive genes or traits as being less capable than others.

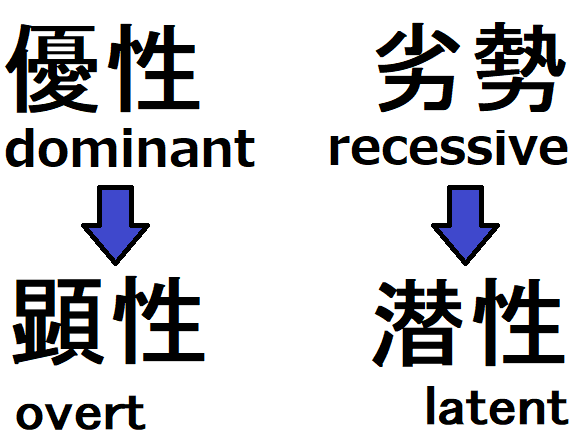

Because of that, the GSJ has revised its internal terminology standards. 優性/yusei/dominant has been replaced with 顕性/akirasei/overt, with 顕 having the meaning of “exposure” or “clarity.” The chosen replacement for 劣性/ressei/recessive is 潜性/sensei/latent, with 潜 representing the condition of latency or being hidden.

GSJ president and University of Tokyo professor Takehiko Kobayashi said that the organization plans to submit a petition to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to have the new terms replace existing ones in textbooks and educational materials. The GSJ will also be releasing a compiled collection of a number of proposed genetics terminology revisions commercially, for 2,800 yen (US$25), sometime later this month.

However, it’s debatable how necessary the change is. The 優 from 優性/dominant also shows up in 優しい/yasashii/kind-hearted, yet Japanese culture has no widely held perception of people with dominant genes being more caring or considerate than people of any other genotype. In the case of long-established compound-kanji vocabulary, native speakers don’t necessarily have their image of the word colored by its kanji components, in much the same way as English speakers don’t get a sense of repetition from the word “respect,” despite its origins lying in the concept of “looking back/repeatedly (hence the “re-“) at someone in admiration.”

There’s also the fact that while 潜性/sensei means “latent,” the kanji 潜 also shows up in the verb 潜む/hisomu, which means “to be hidden,” or, in more sinister contexts, “to lurk.” That’s something which isn’t likely to leave the best impression on people who get caught up on etymology, and may end up being a major sticking point in the GSJ’s bid to have its proposed terms become the new standard.

Source: Asahi Shimbun Digital via Hachima Kiko

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images ©SoraNews24

Follow Casey om Twitter, where he wonders how much trouble would have been averted if Metal Gear Solid’s Liquid Snake understood that recessive genes aren’t bad.

Kansai area people more genetically predisposed to liking coffee than elsewhere in Japan

Kansai area people more genetically predisposed to liking coffee than elsewhere in Japan Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video

Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video Tokyo government announces new name for maternity/paternity leave, hopes to change attitudes

Tokyo government announces new name for maternity/paternity leave, hopes to change attitudes Japanese students despair over the many, MANY ways you can describe a dead flower

Japanese students despair over the many, MANY ways you can describe a dead flower U.S. college student learns the hard way to get your Japanese kanji tattoo checked by an expert

U.S. college student learns the hard way to get your Japanese kanji tattoo checked by an expert McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there

The oldest tunnel in Japan is believed to be haunted, and strange things happen when we go there Arrest proves a common Japanese saying about apologies and police

Arrest proves a common Japanese saying about apologies and police Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】

Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】 Dogs now allowed on Catbus! Ghibli Park vehicles revise service animal policy

Dogs now allowed on Catbus! Ghibli Park vehicles revise service animal policy Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 Tokyo’s most famous arcade announces price increase, fans don’t seem to mind at all

Tokyo’s most famous arcade announces price increase, fans don’t seem to mind at all Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community

We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it?

Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it? There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park

There’s a park inside Japan where you can also see Japan inside the park Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball

Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down

Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train

Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules

Kyoto bans tourists from geisha alleys in Gion, with fines for those who don’t follow rules Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears?

Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears? New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure

Studio Ghibli’s new desktop Howl’s Moving Castle will take your stationery on an adventure Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet

Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet Draft bill proposal seeks to curtail unconventional “kirakira” kanji name readings in Japan

Draft bill proposal seeks to curtail unconventional “kirakira” kanji name readings in Japan Get your name, genetic information engraved on a Japanese name stamp that’s uniquely you

Get your name, genetic information engraved on a Japanese name stamp that’s uniquely you Tired of looking for The One? Try Japan’s new DNA matchmaking service and maybe you’ll find them

Tired of looking for The One? Try Japan’s new DNA matchmaking service and maybe you’ll find them Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice

Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice Genetically altered rice could solve Japan’s pollen allergy problem

Genetically altered rice could solve Japan’s pollen allergy problem Japan slowly begins to openly discuss crossdressing men in heterosexual relationships

Japan slowly begins to openly discuss crossdressing men in heterosexual relationships Iketara iku: A simple Japanese phrase that people in Tokyo and Osaka take completely differently

Iketara iku: A simple Japanese phrase that people in Tokyo and Osaka take completely differently Meaning of life discovered using Japanese calligraphy, math, and puns

Meaning of life discovered using Japanese calligraphy, math, and puns Japan’s Kanji of the Year revealed, reflects both the good and the bad of 2022

Japan’s Kanji of the Year revealed, reflects both the good and the bad of 2022 The three ways to say “love” in Japanese, and when to use them

The three ways to say “love” in Japanese, and when to use them “Ugly” South Korean woman goes from “Old Lady Face” to “Dream Girl” with help of cosmetic surgery

“Ugly” South Korean woman goes from “Old Lady Face” to “Dream Girl” with help of cosmetic surgery W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most difficult kanji ever【Weird Top Five】

W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most difficult kanji ever【Weird Top Five】 Oita lures travelers with wonderful montage of synchronized hot spring bathing 【Video】

Oita lures travelers with wonderful montage of synchronized hot spring bathing 【Video】

Leave a Reply