In the 22nd year of the Meiji era (aka 1889), the very first Japanese kyūshoku (school lunch) was served up at an elementary school in Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture. Although the first menu was very simply prepared, it provided the growing children with an important source of nourishment that not all of them could receive at home.

Fast-forward to 2015–Japanese schoolchildren (and their teachers!) continue to eat school lunches every day, as opposed to children in many other countries who bring their lunches from home. If you’re working in a Japanese school, you should already be familiar with the daily feeling of either excitement or disappointment when you see the lunch menu for the day. But just consider this–would you rather eat the types of lunches served today, or those that were served 100 years ago? Read on to learn about the evolution of Japanese school lunches and decide for yourself!

Love’em or hate’em, school lunches at Japanese schools are here to stay. Everyone, including the teachers and even the principal, sit down to eat the same lunch every day. Children are encouraged to be thankful for the food and finish every last bite, including any foods that they’re not particularly fond of. If you’re interested in learning more about the daily routine revolving around preparing and serving the food, please see our previous post here. Otherwise, let’s dive right into the history of Japanese school lunches!

The Gakkō Kyūshoku website has provided a concise history of the lunches, including pictures of sample meals from different time periods. The following pieces of information and images were taken from their website.

The first school lunch in Japan was started by a Buddhist monk who oversaw a school in Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture. The idea to provide lunch at school came about when he noticed that many of the disadvantaged children weren’t coming to school with packed lunches from home. These first simple lunches consisted of onigiri (rice balls), grilled fish, and pickled vegetables called tsukemono, as seen below:

▼A typical school lunch from year 22 of the Meiji era (1889)

Years later, the people of Yamagata erected a commemorative monument on the school grounds where the first school lunch was served. Here’s what it looks like today:

Word spread about the success of the monk’s school lunch program. Before long, schools around the country had embraced the idea and were beginning to offer lunches to their students as well. Rice mixed with meat and/or vegetables, fish, and varieties of miso soup became typical food items found on the menus.

During these early years, schools usually served the food in porcelain bowls and other dishware, making it feel more like a home-cooked meal than a school-provided lunch.

▼Year 12 of the Taishō era (1923)

▼Year 2 of the Shōwa era (1927)

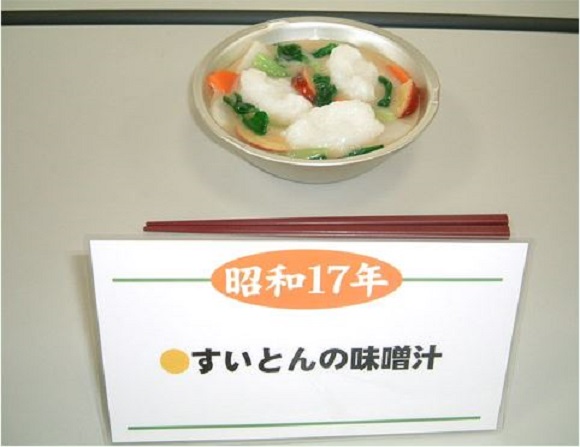

After the outbreak of WWII, school lunches were either cut or reduced in many parts of the country due to local wartime food shortages. The following image is an example of a dumpling miso soup eaten during the war years:

▼Year 17 of the Shōwa era (1942)

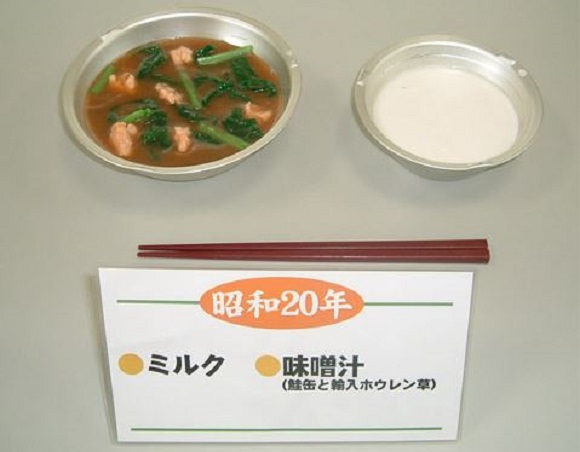

In 1944, approximately two million elementary school-aged children received school lunch in six major cities throughout Japan. Although the war ended in 1945, food shortages continued, and many children were left malnourished. It is estimated that elementary school sixth grade students at the time had bodies equivalent to those of fourth grade students of today due to stunted growth.

Note the inclusion of milk in the sample meal from 1945 below:

▼Year 20 of the Shōwa era (1945)

In 1946, the vice-minister of three governmental ministries released a decree to encourage the widespread implementation of school lunches throughout the country. Consequently, a school lunch system was implemented on December 24 of that year at all schools in Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Chiba prefectures. Today, some schools in those regions offer a special menu during the week of January 24-30 in commemoration (since holidays typically interfere with the final week of December and no school lunch is served then anyway).

In case you were wondering, that’s tomato stew in the picture below.

▼Year 22 of the Shōwa era (1947)

In 1947, approximately three million children around the country began receiving school lunch, including powdered non-fat milk donated from America. Two years later, UNICEF also donated free shipments of the powdered milk.

In 1950, elementary school-aged children in eight major Japanese cities received complete school lunches with the addition of bread made using wheat flour from America. A bread roll coupled with potato stew, croquette, sliced cabbage, and milk is an example of what a typical lunch served during this year would look like:

▼Year 25 of the Shōwa era (1950)

The year 1951 saw a movement unfold throughout the country for school lunches to be partially funded by government subsidies. By the following year, the government funded half the cost of the wheat flour used in school lunch bread. Starting in April, elementary school-aged children in all schools throughout the country received complete school lunches. Lunches over the following years tended to include a number of fried menu items.

▼Year 27 of the Shōwa era (1952)

In 1954, the School Lunch Act was implemented. School lunch was recognized as a legitimate part of children’s education as a way to teach knowledge about how food is produced and important dining customs. It also encouraged healthy social interaction between classmates and within the school, a tenet which is still promoted to this day.

▼Year 30 of the Shōwa era (1955)

▼Year 32 of the Shōwa era (1957)

In 1958, the administrative director of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) promoted an outline for the inclusion of milk in school lunches. Fresh cow’s milk gradually replaced powdered milk over the next several years.

▼Year 38 of the Shōwa era (1963)

The dish on the right-hand side of the tray below is oden, a Japanese favorite in the wintertime!

▼Year 39 of the Shōwa era (1964)

In addition, although bread rolls had been the norm for a long time, fried bread and other forms of cooked bread were being introduced into school lunches by the end of the 1950s (see the above photo). Soft noodles also began to appear in some school lunches in the central Kanto region of Japan.

▼Year 40 of the Shōwa era (1965)

▼Year 45 of the Shōwa era (1970)

In 1971, the contents of school lunches were more or less standardized by governmental decree.

▼Year 49 of the Shōwa era (1974)

▼Year 50 of the Shōwa era (1975)

Meals with warm, freshly cooked rice began to be served in 1976. There was also an increase in the variety of foods served compared to the selection from just two decades before.

▼Year 52 of the Shōwa era (1977)

▼Year 54 of the Shōwa era (1979)

In this next photo, you can see that the previously bottled milk was finally replaced by milk cartons. Continue to track these subtle changes in the remaining images.

▼Year 56 of the Shōwa era (1981)

Egg and spinach gratin, along with shrimp salad and braided bread? How fancy!

▼Year 58 of the Shōwa era (1983)

Even bibimbap, a Korean mixed rice dish, made its debut in 1985. Also, I spy some yummy-looking dessert pudding.

▼Year 60 of the Shōwa era (1985)

▼Year 62 of the Shōwa era (1987)

1993 and 1994 were bad years for rice crops, so school districts were singularly allowed to supplement their school lunches with rice not subject to governmental controls. By 2000, this type of rice became allowed for general usage.

▼Year 12 of the Heisei era (2000)

Japanese school lunches sure have come a long way over the past century. Menus are now more varied and nutritionally balanced to ensure the development of healthy school-aged children.

It’s worth noting that school lunches have also come under fire for issues regarding cleanliness and proper food preparation. In particular, a tragic incident in 1996 in Okayama Prefecture led to the deaths of two children caused by improper food preparation; an additional 468 showed symptoms of food poisoning. A subsequent investigation revealed the presence of E. coli bacteria in their school lunches.

I myself had the privilege to work for two years at a junior high school in Yamagata Prefecture, the original birthplace of Japanese school lunches. While the quality of the meals wasn’t always the greatest, I look back at them fondly for their convenience, low cost (less than 300 yen [US$2.49] per meal), and the opportunity to try a variety of foods that I wouldn’t normally have packed for myself. Plus, nothing beats a bowl of ready-to-eat, steaming rice in the middle of winter!

My school and other schools in the city operated on a rotating menu schedule, which always included a soup, some type of carb, a vegetable side dish, and milk. Bread was usually served on Mondays, noodles on Wednesdays (during cold months only), and rice on the rest of the days. I always looked forward to special holiday meals, which often included an extra special treat or a culturally relevant food.

I think it’s fitting to end this piece with two photos of Yamagata junior high school lunches. Just look at how far they’ve come since 1889!

▼Circa 2012

Sources/Images: Gakkou Kyuushoku, Unilab Tsuruoka, RocketNews24

School Lunch in Japan 【You, Me, And A Tanuki】

School Lunch in Japan 【You, Me, And A Tanuki】 Top 10 Japanese school lunch food items that adults miss the most

Top 10 Japanese school lunch food items that adults miss the most Our Japanese reporter’s encounter with American school lunch

Our Japanese reporter’s encounter with American school lunch Japanese survey takers go back to school to vote on their favorite school lunch menu items

Japanese survey takers go back to school to vote on their favorite school lunch menu items “How I learned to stop worrying and eat Japanese school lunches,” by P.K. Sanjun

“How I learned to stop worrying and eat Japanese school lunches,” by P.K. Sanjun Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Family Mart’s Shibuya Cat Street shop hosts first-ever rescue cat photo exhibition for Cat Day

Family Mart’s Shibuya Cat Street shop hosts first-ever rescue cat photo exhibition for Cat Day Skyscraper sized Pokémon cards to appear in Tokyo all year long in Tocho projection mapping event

Skyscraper sized Pokémon cards to appear in Tokyo all year long in Tocho projection mapping event Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service returns to theaters with first-ever IMAX screenings and remaster

Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service returns to theaters with first-ever IMAX screenings and remaster Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway

Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Osaka icon loses legs, restaurant says famous crab is exhausted

Osaka icon loses legs, restaurant says famous crab is exhausted This Hakata hotel is worth a little extra thanks to its all-you-can-eat steak breakfast buffet

This Hakata hotel is worth a little extra thanks to its all-you-can-eat steak breakfast buffet These apartments are crazy-small even by Tokyo standards, and super-popular with young people

These apartments are crazy-small even by Tokyo standards, and super-popular with young people Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Japanese School Lunch Fail【You, Me, And A Tanuki】

Japanese School Lunch Fail【You, Me, And A Tanuki】 Tokyo government building serves local school lunch to public in Japanese cafeteria

Tokyo government building serves local school lunch to public in Japanese cafeteria Japanese town axes milk from school lunches, debate likely to wage until cows come home

Japanese town axes milk from school lunches, debate likely to wage until cows come home Convenience store fried chicken going into school lunches in Japan for Family Mart anniversary

Convenience store fried chicken going into school lunches in Japan for Family Mart anniversary “Let them eat furikake!” says Mayor Hashimoto as Osaka school lunch saga rumbles on

“Let them eat furikake!” says Mayor Hashimoto as Osaka school lunch saga rumbles on Japanese school lunch noodles fried so hard that children and teachers chip teeth, go to hospital

Japanese school lunch noodles fried so hard that children and teachers chip teeth, go to hospital Hi-Chew releases new Japanese School Lunch flavor to stimulate appetites and nostalgia

Hi-Chew releases new Japanese School Lunch flavor to stimulate appetites and nostalgia Aichi woman arrested for mixing human excrement into school lunch

Aichi woman arrested for mixing human excrement into school lunch Why do kids in Japan use those large leathery “randoseru” school bags?

Why do kids in Japan use those large leathery “randoseru” school bags? Ghibli food brought to life for one week of amazing lunches at elementary school in Japan

Ghibli food brought to life for one week of amazing lunches at elementary school in Japan Okayama students! Ready yer breakfast and eat hearty, Fer lunch ye dine upon wild boar and deer!

Okayama students! Ready yer breakfast and eat hearty, Fer lunch ye dine upon wild boar and deer! Short video looks at why Japanese students serve their own school lunches, clean their classrooms

Short video looks at why Japanese students serve their own school lunches, clean their classrooms In Japanese elementary schools, lunchtime means serving classmates, cleaning the school 【Video】

In Japanese elementary schools, lunchtime means serving classmates, cleaning the school 【Video】 Japanese junior high school student pranks teacher by lacing school lunch with laxative

Japanese junior high school student pranks teacher by lacing school lunch with laxative Foreign student’s comment leads to Japan’s favorite tonkotsu ramen being added to school lunch menu

Foreign student’s comment leads to Japan’s favorite tonkotsu ramen being added to school lunch menu