Linguistics professor explains the centuries-old background of the omnipresent anime and manga verbal tic.

If you’re studying Japanese, three of the first words you’ll learn are arimasu, imasu, and desu. While they all more or less translate into English as “be,” they’re used for different situations in Japanese.

Arimasu is for showing the existence or location of inanimate objects. For example, if you wanted to say “Mt. Fuji is in Japan,” you’d say “Fujisan ha Nihon ni arimasu.” Imasu, on the other hand, is for the existence/location of people and animals. So for “I am in Japan,” it’d be Watashi ha Nihon ni imasu.” And finally, desu is used with adjectives that describe the condition of things or people. “Mt. Fuji is beautiful” is “Fujisan ha kirei desu,” and, if you’re confident enough to make the same boast about your own fetching good looks, it’d be Watashi ha kirei desu.”

But in the world of anime and manga, if the scriptwriter or author is creating dialogue for a Chinese character who’s supposed to be less than fluent, there’s a better-than-even chance the character will completely bypass imasu and desu and just use arimasu, or it’s more casual version, aru, for everything. Instead of the grammatically correct “Watashi ha Chugokujin desu” (“I am Chinese”), you’ll often hear Chinese characters saying “Watashi ha Chugokujin arimasu.”

The weird thing, though, is that you’ll rarely, if ever, hear actual Chinese learners of Japanese putting arimasu at the end of everything like this. So where does this stock speaking style for anime and manga come from? According to Satoshi Kinsui, a linguistics professor at Osaka University, it comes from history.

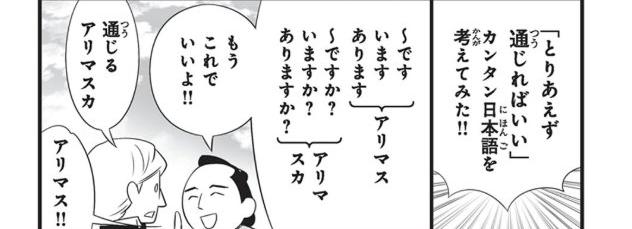

Manga artist Hebizo and author Umino Nagiko asked Kinsui about the “Chinese people say arimasu” stereotype as part of the research for their new book, Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3 (“Japanese Language that Japanese People Don’t Know 3”). Kinsui says this overreaching use of arimasu has its roots in the mid-19th century, as Japan’s feudal Edo period was coming to an end and the modernization of the Meiji period was beginning.

▼ Cover of Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3

With Japan finally opening up to international trade and relations after centuries of government-mandated isolation, there was a sudden influx of foreigners coming into the country. However, this was long before online dictionaries, budget-priced phrasebooks, or other easy ways to bridge low-to-moderate language barriers. So instead, a simplified, pidgin-like version of Japanese came about, in which arimasu, imasu, and desu all got lumped together as arimasu.

▼ One of Hebizo’s illustrations for the book, showing a topknotted Japanese local explaining to a light-haired Westerner that he can still make himself understood even if he lumps desu (です), imasu (います), and arimasu (あります) all together as just arimasu.

But as the caricatured Kinsui himself points out, this form of simplified Japanese was used by foreigners of many different nationalities, not just those who spoke Chinese as their native language. So why has the verbal tick been attached so firmly to Chinese anime characters?

Kinsui himself doesn’t address the question, but a couple of possibilities come to mind. First, Kinsui mentions that the “everything is arimasu” style of pidgin also seems to have been used in Japanese-occupied China, with the Imperial Japanese Army holding on to those territories until the end of World War II. On the other hand, few foreigners were coming into Japan during its era of military aggression. Once the war was over many of the foreigners in the country were part of the occupying Allied Forces, and the balance of power became such that Japanese businessmen and politicians were now expected to be able to communicate in English for international affairs. That would make the era of arimasu-style pidgin a few decades more recent among native speakers of Chinese than other languages, and could be why Chinese anime characters are so much more likely than any other ethnicity to speak that way.

▼ A selection of pages from Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3

アニメの博士はなぜ「~じゃ」と話すのか。謎の中国風キャラはなぜ「アルヨ」と話すのか。実際にそんな人見たことないのに!

— 蛇蔵@天地創造デザイン部8巻発売中 (@nyorozo) November 3, 2018

という疑問に答える漫画を描いたことがあるのでどうぞ。https://t.co/hXaliIfPXc pic.twitter.com/XrMg1MvHqV

There’s also the practice that when looking for dialogue-based ways to emphasize a character’s foreignness, if said character is from a Western background, anime creators often just have the character speak English, or pepper their Japanese dialogue with English vocabulary that Japanese audiences will be at least somewhat familiar with. English is a required subject in Japanese schools, and loanword-loving Japanese has adopted a large number of English terms, so it’s a simple matter to have, for example, an American character suddenly say “Great!” instead of “Ii na! or “Me ha very happy desu,” instead of “Watashi ha totemo shiawase desu.”

Doing that makes the character still sound foreign, but also leaves the dialogue understandable to a Japanese audience (even if the English isn’t being used like an actual English-speaker would use it). But with the average Japanese person far less familiar with basic Chinese vocabulary, that’s not a viable dialogue-writing option, leaving many creators falling back on just slapping arimasu at the end of Chinese characters sentences.

▼ English being a required subject also no doubt makes it easier to ask anime voice actors to power through a few lines of English dialogue than to do the same with Chinese.

Granted, anime and manga are first and foremost entertainment media, and having a simple way of telling he audience “This person isn’t a Japanese national” lets creators quickly move on to what they want to focus their storytelling on. Still, the fact that real world Chinese natives who’re learning Japanese don’t put arimasu at the end of all their sentences can be irksome and distracting for anyone who’s spent much time around learners of Japanese as a second language.

Source: Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3, Twitter/@nyorozo

Top image: Pakutaso

Insert images: Nihonjin no Shiranai Nihongo 3, Twitter/@nyorozo

[ Read in Japanese ]

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he has to admit he is fond of using the word “GET!” when speaking Japanese.

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 2)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 2) How to respond to Japanese people saying “I don’t speak English” when you’re speaking Japanese?

How to respond to Japanese people saying “I don’t speak English” when you’re speaking Japanese? Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1) Some thoughts on Netflix’s Evangelion anime translation controversy, like, and love

Some thoughts on Netflix’s Evangelion anime translation controversy, like, and love What’s the best Rumiko Takahashi anime of all time? Fans decide, pick best characters too【Survey】

What’s the best Rumiko Takahashi anime of all time? Fans decide, pick best characters too【Survey】 Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Family Mart’s Shibuya Cat Street shop hosts first-ever rescue cat photo exhibition for Cat Day

Family Mart’s Shibuya Cat Street shop hosts first-ever rescue cat photo exhibition for Cat Day Skyscraper sized Pokémon cards to appear in Tokyo all year long in Tocho projection mapping event

Skyscraper sized Pokémon cards to appear in Tokyo all year long in Tocho projection mapping event Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service returns to theaters with first-ever IMAX screenings and remaster

Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service returns to theaters with first-ever IMAX screenings and remaster Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway

Development of Puyo Puyo puzzle game for use in nursing homes underway Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Osaka icon loses legs, restaurant says famous crab is exhausted

Osaka icon loses legs, restaurant says famous crab is exhausted This Hakata hotel is worth a little extra thanks to its all-you-can-eat steak breakfast buffet

This Hakata hotel is worth a little extra thanks to its all-you-can-eat steak breakfast buffet These apartments are crazy-small even by Tokyo standards, and super-popular with young people

These apartments are crazy-small even by Tokyo standards, and super-popular with young people Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics]

Is Sapporio’s Snow Festival awesome enough to be worth visiting even if you hate the snow? [Pics] Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why?

Japan has trams that say “sorry” while they ride around town…but why? Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies

Sakura Totoro is here to get spring started early with adorable pouches and plushies Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season

Poop is in full bloom at the Unko Museums for cherry blossom season Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month

Shibuya Station’s Hachiko Gate and Yamanote Line stairway locations change next month Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are

Japan’s new “Cunte” contact lenses aren’t pronounced like you’re probably thinking they are Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says