Commonly used kanji’s components don’t make a lot of sense nowadays, but once upon a time…

The Japanese language has three types of writing, and kanji are by far the most difficult. There are more than 2,000 kanji characters to remember, and that huge number is a daunting goal not just for foreigners learning Japanese as a second language, but for kids growing up in Japan as well.

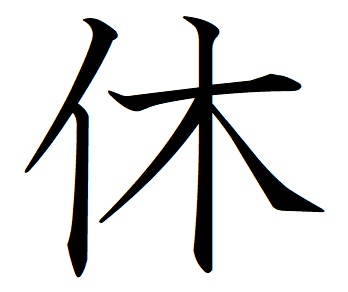

But while learning kanji is always going to be a challenge, there’re a few ways to make it more manageable, and one of the best is to look for ways to break a single kanji down into its component parts. For example, the kanji character for “rest,” seen here…

…becomes easier to remember if you already know that 木 is the kanji for “tree,” and the left portion of 休 represents a person. In other words, the kanji for “rest” is a picture of a person leaning against a tree, taking a break and relaxing in the shade.

So yeah, kanji can be tough, but the more you learn, the easier they get…at least that’s usually how it goes. However, you might find yourself scratching your head when you come to the kanji for “take…”

…since the left half is pretty much the same as the kanji for ear.

But maybe things instantly make sense when you add in the right half of 取? Not really, since the right portion means “hand,” making 取 a visual representation of “holding an ear.”

And it’s not like the metaphor is “grab someone by the ear to take them somewhere with you” either, since that meaning for the English word “take” (i.e. forcibly leading someone somewhere) is a completely separate word/kanji in Japanese (連). No, 取 is strictly for the idea of willfully obtaining something, but why is it the concept connected to ears?

Because long ago, if you were a soldier on the field of battle, and you wanted to bring proof back to camp that you’d killed a bunch of dudes, you’d cut off the ears of your fallen foes.

▼ It was, after all, an age where far more people had swords on them than camera-equipped phones.

With “take” being such a necessary, fundamental communication concept, and kanji having been in use for centuries, originally in China and later in Japan, 取, and the reason it’s written the way it is, aren’t new linguistic developments. 取 is one of the most commonly written/typed kanji, though, and with its components themselves being fairly simple and easy to remember, many Japanese people haven’t really bothered to dig into its conceptual origins. Recently, though, Japanese Twitter user and linguistics tutor @tutor_gonta brought the violent backstory to people’s attention while sharing that he himself only learned about it recently when a third-grade pupil asked him why 取 is written that way, and both of them were shocked when he looked into the reason.

小3の生徒に「どうして『取る』っていう字は耳へんなんですか?」と聞かれ、私も知らなかったのでその場で漢字字典で調べたところ『捕虜や敵の耳を戦功の印としてしっかり手に持つことを表す』と書かれていて、生徒と二人でぶるぶる震えた。

— ごん太@家庭教師 (@tutor_gonta) March 13, 2021

In the meantime, if you’d like to learn the origins of a less bloodstained kanji, can we interest you in why “cherry blossom” is written the way it is in Japanese?

Sources: Fusen Arare no Kanji Blog, OKjiten

Top image: Pakutaso (edited by SoraNews24)

Insert images: SoraNews24, Pakutaso

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

Follow Casey on Twitter for more about Japanese linguistics and/or swords.

Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet

Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video

Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video Renowned Japanese calligraphy teacher ranks the top 10 kanji that foreigners like

Renowned Japanese calligraphy teacher ranks the top 10 kanji that foreigners like Poop Kanji-Drill toilet paper is the best way to accomplish your Japanese studying doo-ties

Poop Kanji-Drill toilet paper is the best way to accomplish your Japanese studying doo-ties Kanji Tetris is the coolest way to practice and play with Japanese that we’ve ever seen【Video】

Kanji Tetris is the coolest way to practice and play with Japanese that we’ve ever seen【Video】 Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration

Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan

How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide

Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience

Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir

New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir Studio Ghibli releases Ponyo donburi bowl to bring anime ramen to life

Studio Ghibli releases Ponyo donburi bowl to bring anime ramen to life New Nintendo Lego kit is a beautiful piece of moving pixel art of Mario and Yoshi【Photos】

New Nintendo Lego kit is a beautiful piece of moving pixel art of Mario and Yoshi【Photos】 Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys

Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】

High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】 “The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】

“The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】 Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan

Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters

Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches

McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous?

Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous? Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not

Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists

Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners

To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners 10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan

10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear

Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka

Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model

Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose

Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】

Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】 Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Tired of wasting paper practicing your kanji? Try these reusable water-activated practice sheets

Tired of wasting paper practicing your kanji? Try these reusable water-activated practice sheets Japanese government tells teachers not to be so strict, at least about some kanji radicals

Japanese government tells teachers not to be so strict, at least about some kanji radicals “Gold” named 2016 Kanji of the Year

“Gold” named 2016 Kanji of the Year The hidden meaning of the U.S. Air Force’s “shake and fries” patch in Japan

The hidden meaning of the U.S. Air Force’s “shake and fries” patch in Japan W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most difficult kanji ever【Weird Top Five】

W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most difficult kanji ever【Weird Top Five】 Four new era names the Japanese government rejected before deciding on Reiwa

Four new era names the Japanese government rejected before deciding on Reiwa Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice

Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice What’s funnier and more likely to make you study than poo? How about male pattern baldness?

What’s funnier and more likely to make you study than poo? How about male pattern baldness? Tokyo government announces new name for maternity/paternity leave, hopes to change attitudes

Tokyo government announces new name for maternity/paternity leave, hopes to change attitudes Japanese teacher’s explanation about “individuality” to kids has a deep, beautiful meaning

Japanese teacher’s explanation about “individuality” to kids has a deep, beautiful meaning Japan’s top baby names for 2015: Will Naruto-influenced monikers still reign supreme?

Japan’s top baby names for 2015: Will Naruto-influenced monikers still reign supreme? 11 different ways to say “father” in Japanese

11 different ways to say “father” in Japanese Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita

Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita Anime-style magic circles summon vocabulary for you in this language-learning app from Japan【Vid】

Anime-style magic circles summon vocabulary for you in this language-learning app from Japan【Vid】 Dodge the biggest problem of giving yourself a kanji name with these for-foreigner personal seals

Dodge the biggest problem of giving yourself a kanji name with these for-foreigner personal seals How do Japan’s host club hosts get their professional names? We talk with five Kabukicho pros

How do Japan’s host club hosts get their professional names? We talk with five Kabukicho pros Draft bill proposal seeks to curtail unconventional “kirakira” kanji name readings in Japan

Draft bill proposal seeks to curtail unconventional “kirakira” kanji name readings in Japan

Leave a Reply