He got his start in tuna wholesale when he was just 16, and today we’re learning from his experience.

Tuna, or maguro, as it’s called in Japanese, is one of Japan’s very favorite kinds of fish. It’s most popular raw, either sliced as sashimi, placed atop blocks of vinegared rice as sushi, or used as the topping for a maguro rice bowl.

Because it’s such a staple of the Japanese diet, you can find blocks of sashimi-grade tuna in any grocery store in the country. That’s definitely something to be happy about, but it also presents a puzzle: Which block should you choose for maximum deliciousness?

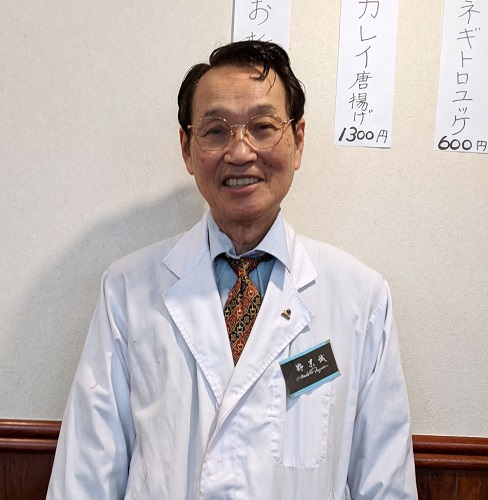

To find out, we took a trip to Tsukuda Takisaburo, a sushi restaurant in Tokyo’s Toyosu neighborhood, not far from the city’s massive fish market. The restaurant is part of the company Nariichi Sakahama, a fish wholesaler, and they’d set up a meeting between us and Makoto Nosue, their special advisor.

The 84-year-old Nosue first started working in the tuna wholesale business when he was just 16 years old, and he’s been in it ever since. He made a name for himself when Tokyo’s main fish market was still located in Tsukiji, and even now he regularly gets up at 3 a.m. to head to the new facility in Toyosu to pick out tuna for Nariichi Sakahama and their restaurant.

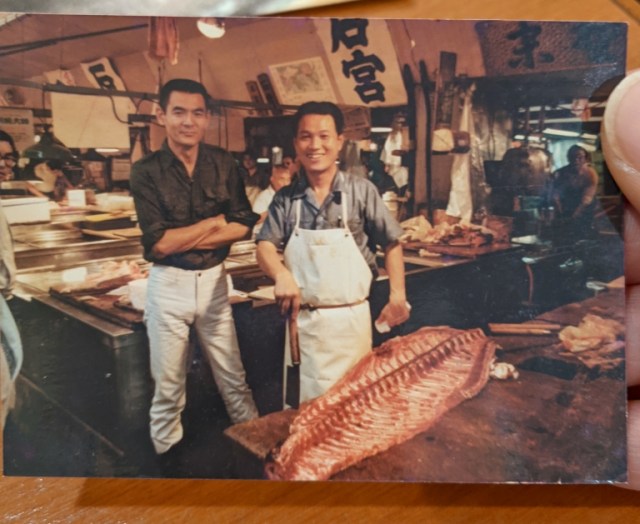

▼ Nosue (right) in his younger days, posing with actor Bunta Sugawara

Our Japanese-language reporter Mr. Sato was eager to glean what knowledge he could from this maguro master with 66 years of experience, and wasted no time in asking the question that’s been captivating his mind and stimulating his appetite.

Sato: “Mr. Nosue, thank you for taking the time to talk with me today. I’ll get right to it. I want to eat good tuna, but when I go to the supermarket there are so many different kinds, so are there any hints for picking a good block?”

Nosue: “Well, it’d probably be hard to understand if I just explained it in words, so I’ve prepared a selection of maguro cuts, some from our wholesaling business, and some from the supermarket.

Sato: “So, I’m guessing this is like the most basic of basic things, but between wild-caught and farm-raised tuna, wild tuna tastes better, right?”

Nosue: “Actually, we can’t just say that wild tuna tastes better, because it depends on how you’re going to prepare and eat the fish. Farm-raised tuna just has a bit of an image problem, in that there’s a tendency for people to assume that wild tuna is better.”

“For example, farm-raised tuna goes extremely well with vinegared rice, so many sushi restaurants use it instead of wild tuna.”

Sato: “Oh wow I had no idea! I’d just always kind of figured wild must be better…”

Nosue: “You can even find expensive sushi restaurants in Ginza that use farm-raised maguro. Between the two, farm-raised tuna tends to have more fat. Wild tuna is leaner, which makes it the better choice if you’re going to broil or stew it. So really the thing to do is consider how you’re going to eat the tuna, and use that to determine whether you should go for wild or farm-raised.

▼ 養殖, the kanji for youshoku/“farm-raised,” as opposed to 天然/tennen/”wild”

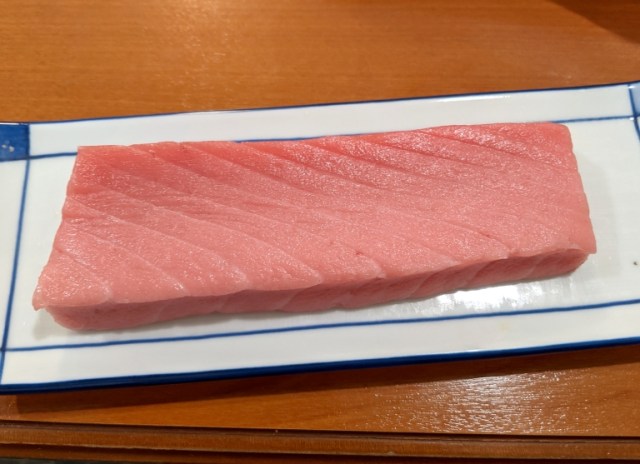

▼ As proof of the potential of farm-raised maguro, Nosue brought out a stunningly beautiful farm-raised tuna block from their wholesale business, and it took all of Mr. Sato’s willpower to not just start gnawing on it right then and there.

Sato: “Okay, but between frozen and non-frozen maguro, the non-frozen kind has got to be better, right?”

Nosue: “That’s also a misconception. Frozen maguro is quite tasty, and it actually has the fresher flavor, since they freeze it right after it’s caught.

Sato: “Ah, that makes sense! But then why do people think frozen maguro doesn’t taste as good?”

Nosue: “Yes, people do often say ‘Frozen maguro doesn’t taste as good.’ But really, the problem is with how the fish was defrosted before they purchased it.”

“What often happens is that the fish hasn’t been completely thawed while they’re eating it. There are still ice crystals inside the fish, and ones that have just recently melted, so they’re not just eating maguro, they’re eating water too, so naturally the flavor of the fish gets watered down. So the important thing to do is to make sure you get rid of that unwanted moisture.”

Nosue then demonstrated how to do just that. First, wrap the cut of tuna in paper towels or butcher paper.

Then, press against the fish gently but firmly with the palms of your hands. This should draw out some of the water and moisten the towel.

Repeat this two or three times, then remove the towel, cover the fish with plastic wrap, and put it in the refrigerator until you’re ready to eat it. And if you want to double-check if your fish is frost-free, Nosue says to pick it up by the middle part and balance it atop your fingers. If the block of fish shows a natural-looking curve, like in the photo below, then it’s good, but if it’s stiff and resists bending, it probably still has ice crystals or excess water in it.

Okay, so now we know farm-raised tuna (養殖) can be just as good as wild (天然), if not better, and maguro that’s been shipped frozen (冷凍) actually has advantage over non-frozen (生), provided we make sure it’s thoroughly thawed. Anything else we should be aware of?

Nosue: “It might be unkind of me to say this, but this block of tuna, which I bought at the supermarket, is the kind you should probably avoid.”

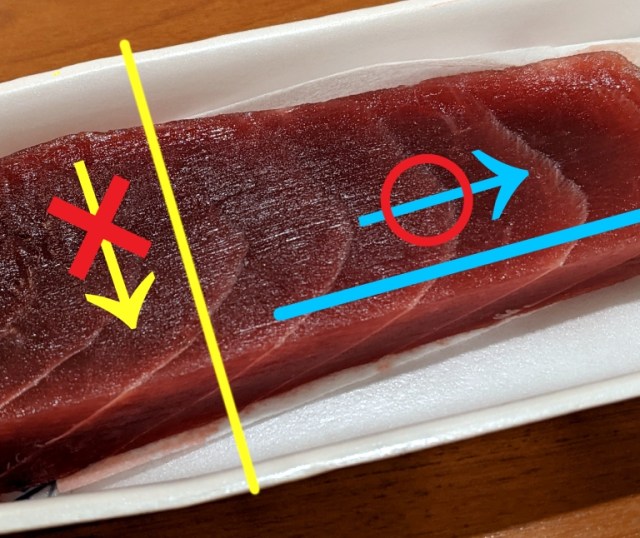

According to Nosue, the problem is how the tendons (the white lines in the fish) are oriented. Because they’re going lengthwise across the block, if you just start making vertical cuts, which would seem to be the most natural way to slice the fish, you’re going to get a lot of tough, stringy texture in each mouthful. When you have a choice, a block where the lines go diagonally across, like in the photo below, will make for a smoother texture and more pleasant chewing sensation, he says.

That said, it’s not like all hope is lost if you have a block of tuna with horizontal tendon lines. You just need to slice it a little counterintuitively, making lengthwise cuts. You’ll might still need to make one or two cuts across the fish in order to keep the pieces bite-sized, and so a little toughness at the edges isn’t going to be something you can completely avoid, but still, it’ll come out better than making nothing but vertical cuts.

▼ Cut like blue arrow, not the yellow one.

Speaking of slicing, Nosue says that a thickness of one centimeter (0.4 inches) is ideal for sashimi that’s being eaten by itself, say, as a snack with a glass of beer or cup of sake. For actual mealtime maguro, he recommends a thinner slice of three to four millimeters. He’s got some serving temperature suggestions, too, saying that 12 degrees Celsius (53.6 degrees Fahrenheit) will give you the best flavor in the summer, and 15 Celsius (59 Fahrenheit) is the best in the winter.

▼ Presumably spring and autumn maguro should be somewhere in between those temperatures.

That’s a lot of numerical advice, but then again, the guy’s been in the maguro game for an impressive number of years, and with all of his pointers being pretty easy to follow, even following just a few of them sounds like it’ll make our home sushi/sashimi sessions better than ever.

Photos ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Which Japanese conveyor belt sushi chain has the best tuna sushi?【Taste test】

Which Japanese conveyor belt sushi chain has the best tuna sushi?【Taste test】 There’s only one place in Japan where this kind of sushi isn’t red, but why?

There’s only one place in Japan where this kind of sushi isn’t red, but why? Yaizu: Japan’s best sushi market destination even most foodies in Japan have never heard of

Yaizu: Japan’s best sushi market destination even most foodies in Japan have never heard of Huge tuna fish sells for a whopping 190 million yen at the first wholesale auction of the year

Huge tuna fish sells for a whopping 190 million yen at the first wholesale auction of the year Bluefin tuna fish sells for bargain low price of roughly US$200,000 in Tokyo auction

Bluefin tuna fish sells for bargain low price of roughly US$200,000 in Tokyo auction How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan

How to order snacks on a Shinkansen bullet train in Japan Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba gets new roller coaster attractions and food at Universal Studios Japan New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir

New samurai glasses are Japan’s latest weird must-have souvenir Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide

Burger King Japan suddenly adds Dr. Pepper and Dr. Pepper floats to its menu nationwide Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys

Nintendo history you can feel – Super NES, N64, and GameCube controllers become capsule toys High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】

High-fashion Totoro cuddle purse is like an elegant stroll in the forest【Photos】 Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience

Japan’s new difficult-to-drink-from beer glass protects your liver, but it’s a brutal experience Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters

Kyoto Tower mascot termination reveals dark side behind cute Japanese characters New Pokémon ice cream, dessert drinks, and cool merch coming to Baskin-Robbins Japan【Pics】

New Pokémon ice cream, dessert drinks, and cool merch coming to Baskin-Robbins Japan【Pics】 To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners

To combat declining birth rate, Japan to begin offering “Breeding Visas” to foreigners Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration

Hello, cosmetics! Clinique teams up with Hello Kitty this summer for first-time collaboration “The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】

“The most Delicious Cup Noodle in history” – Japan’s French Cup Noodle wins our heart【Taste test】 Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan

Starbucks releases a cute Frappuccino and Unicorn Cake…but not in Japan McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches

McDonald’s Japan’s Soft Twist Tower: A phantom ice cream only sold at select branches Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous?

Yabai Ramen: What makes this Japanese ramen so dangerous? Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not

Finally! Nintendo Japan expands Switch 8-bit controller sales to everybody, Online member or not Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists

Japanese government wants to build luxury resorts in all national parks for foreign tourists 10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan

10 things you should buy at 7-Eleven in Japan Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear

Studio Ghibli releases anime heroine cosplay dresses that are super comfy to wear Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka

Woman charged for driving suitcase without a license in Osaka Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model

Studio Ghibli unveils My Neighbour Totoro miniature house model Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose

Kyoto experiencing problems with foreign tourists not paying for bus fares, but not on purpose Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】

Fighting mild hunger with a Japanese soda that turns into jelly in the stomach【Taste test】 Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle tapestry unveiled in Japan for first time McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society

Foreigner’s request for help in Tokyo makes us sad for the state of society Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Hungry in Tokyo’s Ueno? This restaurant’s all-you-can-eat sushi bowl deal is all you need

Hungry in Tokyo’s Ueno? This restaurant’s all-you-can-eat sushi bowl deal is all you need Rare ghost-white tuna caught off Bali — we go to see it on display in Shibuya!

Rare ghost-white tuna caught off Bali — we go to see it on display in Shibuya! Tokyo restaurant wins prized tuna at New Year auction for 114.2 million yen and serves it up to customers

Tokyo restaurant wins prized tuna at New Year auction for 114.2 million yen and serves it up to customers Semi-secret Shinjuku sushi lunch is a great way to get your fish fix for cheap in central Tokyo

Semi-secret Shinjuku sushi lunch is a great way to get your fish fix for cheap in central Tokyo RocketKitchen: A simple and delicious recipe for cooking tuna

RocketKitchen: A simple and delicious recipe for cooking tuna Who’s got the best, cheapest one-person sushi delivery in downtown Tokyo? Mr. Sato investigates!

Who’s got the best, cheapest one-person sushi delivery in downtown Tokyo? Mr. Sato investigates! Tuna born from mackerel: Japanese scientists develop surrogate tech to save threatened species

Tuna born from mackerel: Japanese scientists develop surrogate tech to save threatened species Upcoming party in Shibuya combines house music with cutting open a tuna, girls get in free

Upcoming party in Shibuya combines house music with cutting open a tuna, girls get in free Supermarket sushi becomes a hot topic with foreigners on Reddit, but is it any good?

Supermarket sushi becomes a hot topic with foreigners on Reddit, but is it any good? What’s the best type of sushi to end a meal on? Japanese survey picks the pieces

What’s the best type of sushi to end a meal on? Japanese survey picks the pieces Japan super budget dining – What’s the best way to spend 1,000 yen at sushi restaurant Sushiro?

Japan super budget dining – What’s the best way to spend 1,000 yen at sushi restaurant Sushiro? Japan’s biggest ham company is making “tuna” that contains neither ham nor fish

Japan’s biggest ham company is making “tuna” that contains neither ham nor fish Japanese people list their top ten fish, and tuna isn’t number one

Japanese people list their top ten fish, and tuna isn’t number one Which Japanese conveyor belt sushi chain has the best bintoro sushi?【Taste test】

Which Japanese conveyor belt sushi chain has the best bintoro sushi?【Taste test】 J-rock legend Gackt says he only eats the fish part of his sushi, never touches the rice

J-rock legend Gackt says he only eats the fish part of his sushi, never touches the rice Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo

Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo

Leave a Reply