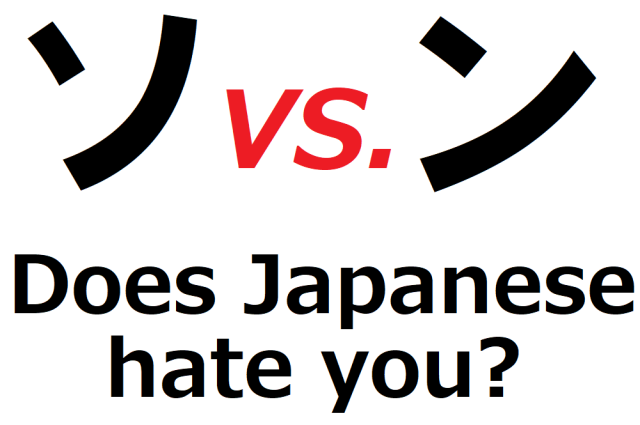

Katakana is supposed to be the easy set of Japanese characters to learn, but there’s a huge exception.

As we’ve talked about before, the Japanese language has three kinds of writing. There’s kanji, the characters originally imported from China in which each one stands for a concept, and also hiragana and katakana, which are both phonetic sets, in which each character stands for a sound.

For most native English-native students of Japanese and expats living in Japan, katakana is by far the easiest. In contrast to the literally thousands of kanji you need to learn to become fluent, there are only 46 hiragana and 46 katakana, and katakana’s more angular shape makes them closer in appearance to the Latin alphabet, and thus easier to remember.

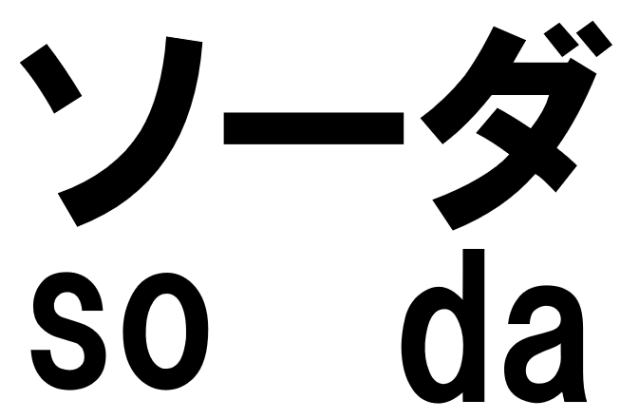

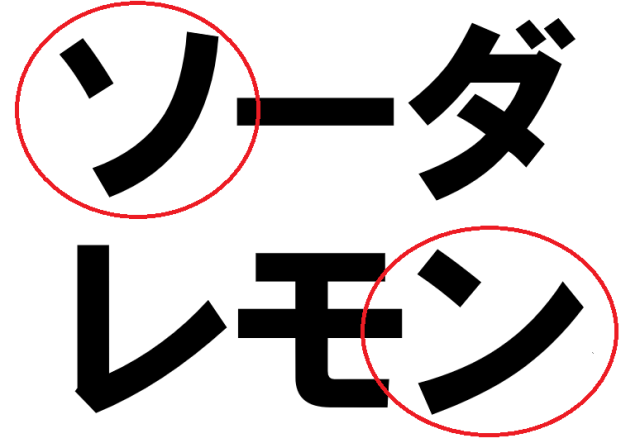

Then there’s the fact that since katakana are used to write foreign loanwords and names, they’re immediately useful, since they’re used to spell vocabulary a native English speaker might already know. For example, in katakana “soda,” as in the fizzy drink, looks like this:

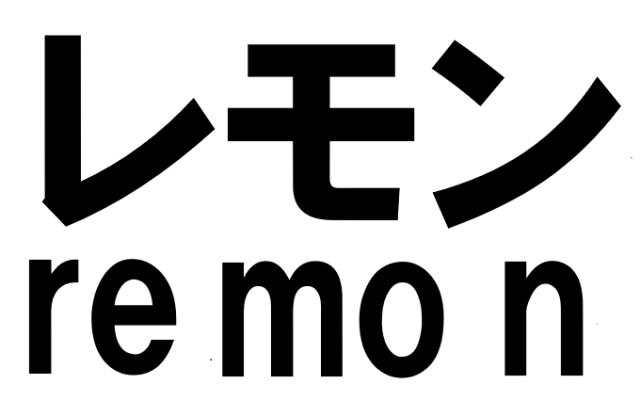

Same deal if you’re writing “lemon” in Japanese (though the L switches to an R, since Japanese doesn’t have Ls): you use katakana.

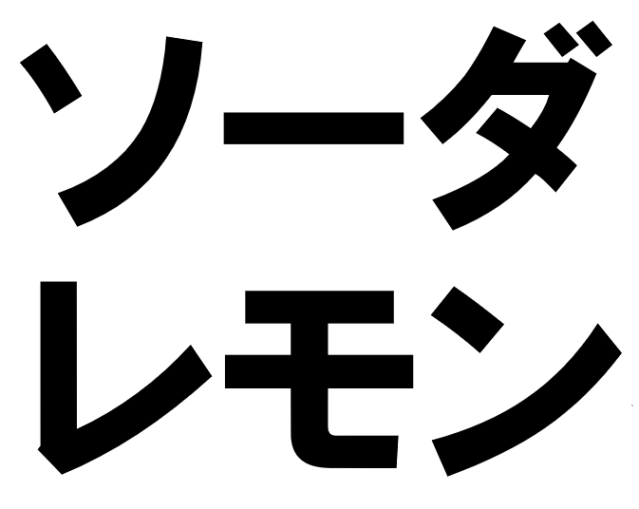

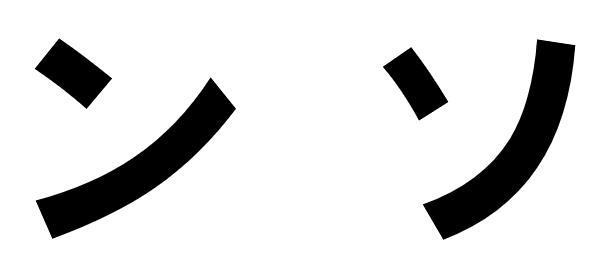

But…wait. Let’s take another look at the katakana versions of “soda” and “lemon.”

How come the same katakana is pronounced “so” in “soda,” but “n” in “lemon?”

Because they’re actually not the same katakana. While they might look identical at first glance, to the trained eye those are two different characters, with two different pronunciations.

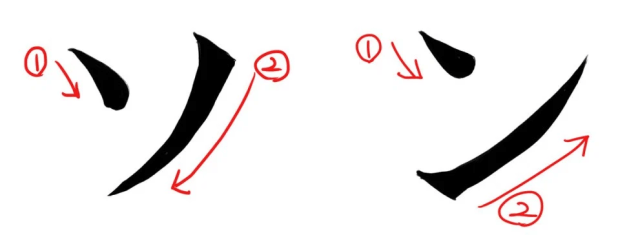

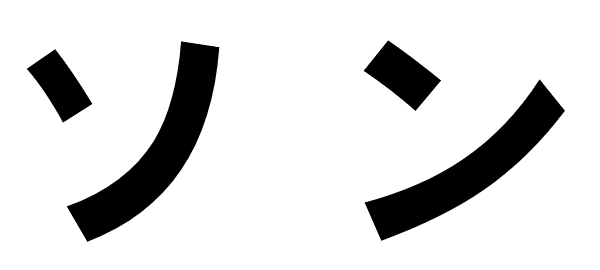

Okay, so how do you train your eye? While it might seem kind of counterintuitive, one way is to understand how the “so” and “n” katakana are written. In both causes, you start with the smaller stroke, but for “so,” that first stroke curves slightly downwards, while for “n” it curves up. The more significant difference, though, is in the direction you write the longer stroke in. For “so,” it’s a downward stroke, and for “n”it’s an upwards one.

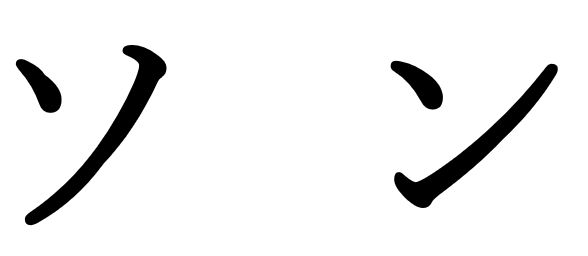

That might not seem so important, but if the katakana are written with a brush, or a font that imitates brushstrokes, the longer strokes for these characters will be thicker at their start, and narrower at their end. That makes “so’s” longer stroke thick at the top, and “n’s” thicker at the bottom.

▼ “so” (left) and “n” (right)

▼ Soda (top) and lemon (bottom)

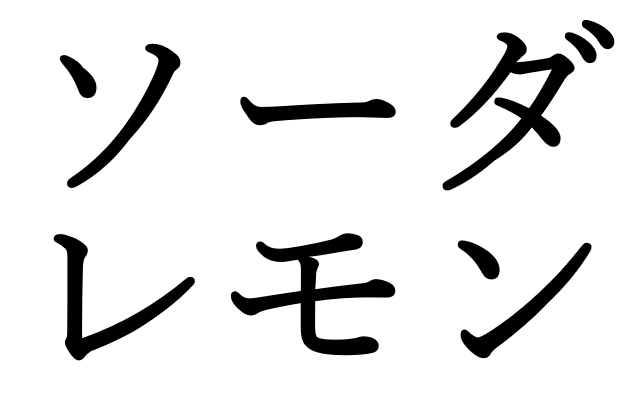

Unfortunately, those stroke order/thickness clues can often disappear with modern, blockier fonts.

For example, you know how in the side-by-side examples so far, “so” had been on the left, and “n” on the right? Did you notice they’re switched directly above, and it’s “n” on the left?

▼ And now they’re flipped again, with “so” back on the left.

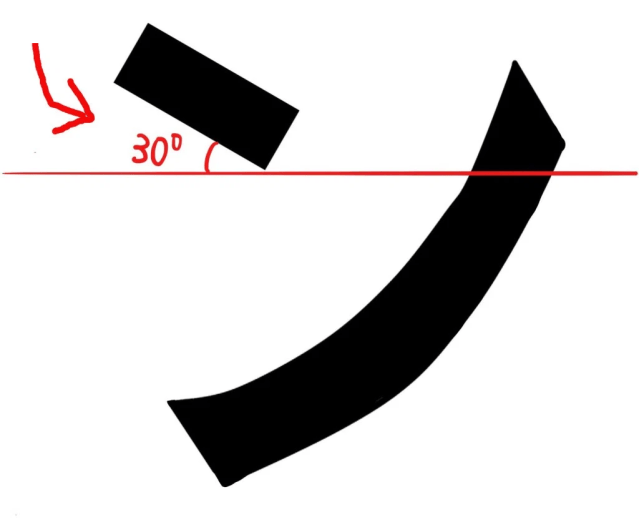

So what’re you supposed to do when confronted with a non-brushstroke font, other than deciding to study Spanish instead? Easy: you look for the angle of the short stroke.

Or, well, sort of easy. See, while the short stroke won’t have any curvature to it in a blocky font, it should be closer to horizontal for “n,” and closer to vertical for “so.” However, the stroke isn’t supposed to be entirely flat or straight up and down. Penmanship pros say it should be at about a 30-degree angle for “n,” and a larger one for “so.”

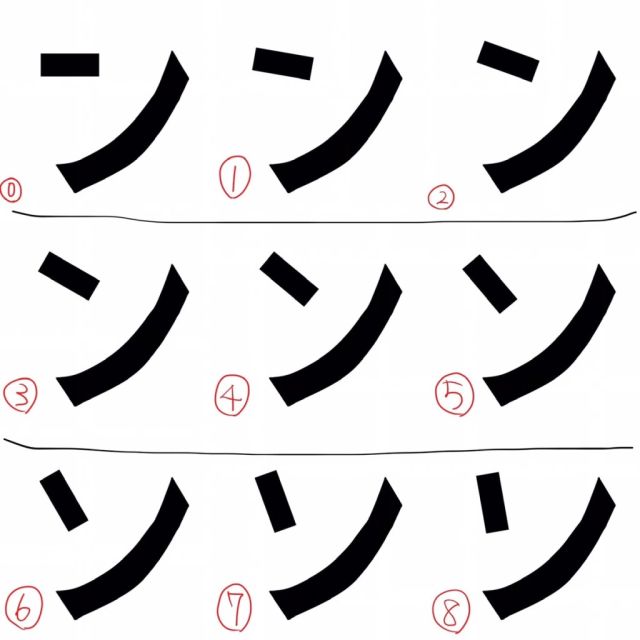

That said, it’s not like people in Japan carry around protractors to use when reading and writing, and the exact point where the angle of the short stroke leaves the “n” zone and crosses over into the alternate “so” world is kind of a gray area. We decided to run a little test, slowly twisting the short stroke from 0 to 80 degrees, and ask our native-Japanese coworkers to tell us where they feel the cutoff is.

We collected 20 responses, and the results were:

● It’s “n” if it’s under 60 degrees, after that it’s “so” (9 votes)

● It’s “n” if it’s under 50 degrees (8 votes)

● It’s “n” if it’s under 40 degrees (3 votes)

If you’re still feeling a little lost, don’t beat yourself up too badly. As our survey shows, even Japanese people don’t have a complete consensus on the visual differences between “so” and “n,” but the more time you spend practicing reading Japanese, the easier it’ll get to sort them out. And if this has you feeling like Japanese is an impossible language to learn, cheer up, because in a lot of ways it’s really not that bad.

Images ©SoraNews24

● Want to hear about SoraNews24’s latest articles as soon as they’re published? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

[ Read in Japanese ]

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he first started remembering katakana from the spines of Bubblegum Crisis soundtrack CDs and the Street Fighter II instruction booklet.

[ Read in Japanese ]

Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character

Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 1) Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 2)

Why does Japanese writing need three different sets of characters? (Part 2) Clever font sneaks pronunciation guide for English speakers into Japanese katakana characters

Clever font sneaks pronunciation guide for English speakers into Japanese katakana characters German linguist living in Japan says kanji characters used for Germany are discriminatory

German linguist living in Japan says kanji characters used for Germany are discriminatory Sakura Festival in Chiyoda mixes illuminations, boats, music, and Rilakkuma in the heart of Tokyo

Sakura Festival in Chiyoda mixes illuminations, boats, music, and Rilakkuma in the heart of Tokyo Viral Japanese cheesecake from Osaka has a lesser known rival called Aunt Wanda

Viral Japanese cheesecake from Osaka has a lesser known rival called Aunt Wanda Chance to play Teris on a massive staircase in Kyoto Station coming in March

Chance to play Teris on a massive staircase in Kyoto Station coming in March Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura cherry blossom collection for hanami season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura cherry blossom collection for hanami season 2026 Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels

Japan’s craziest burger chain takes menchi katsu to new extreme levels Kyoto raises hotel accommodation tax to fight overtourism, travelers could pay up to 10 times more

Kyoto raises hotel accommodation tax to fight overtourism, travelers could pay up to 10 times more Survey finds more than 70 percent of Japanese children have an online friend

Survey finds more than 70 percent of Japanese children have an online friend Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results

Which convenience store onigiri rice balls are the most popular? Survey reveals surprising results Why is Japan such an unpopular tourist destination?

Why is Japan such an unpopular tourist destination? The best Hobonichi diaries, covers and stationery for 2026

The best Hobonichi diaries, covers and stationery for 2026 Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino

Starbucks Japan releases first-ever Hinamatsuri Girls’ Day Frappuccino Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring

Japanese restaurant chain serves Dragon Ball donuts and Senzu Beans this spring Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky

Highest Starbucks in Japan set to open this spring in the Tokyo sky Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 1] Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】

Japan has only one airport named after a samurai, so let’s check out Kochi Ryoma【Photos】 Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2]

Japan Extreme Budget Travel! A trip from Tokyo to Izumo for just 30,000 yen [Part 2] Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven?

Japanese drugstore sells onigiri at pre-stupid era prices, but how do they compare to 7-Eleven? Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant

Yakuzen ramen restaurant in Tokyo is very different to a yakuza ramen restaurant Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season

Tokyo Skytree turns pink for the cherry blossom season Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video]

Japan’s newest Shinkansen has no seats…or passengers [Video] Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan releases new sakura goods and drinkware for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido

Foreigners accounting for over 80 percent of off-course skiers needing rescue in Japan’s Hokkaido Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed

Super-salty pizza sends six kids to the hospital in Japan, linguistics blamed Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026

Starbucks Japan unveils new sakura Frappuccino for cherry blossom season 2026 Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism

Foreign tourists in Japan will get free Shinkansen tickets to promote regional tourism The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals

The 10 most annoying things foreign tourists do on Japanese trains, according to locals Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth

Take a trip to Japan’s Dododo Land, the most irritating place on Earth Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos]

Naruto and Converse team up for new line of shinobi sneakers[Photos] Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant?

Is China’s don’t-go-to-Japan warning affecting the lines at a popular Tokyo gyukatsu restaurant? Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer

Survey asks foreign tourists what bothered them in Japan, more than half gave same answer Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo

Japan’s human washing machines will go on sale to general public, demos to be held in Tokyo Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day

Starbucks Japan releases new drinkware and goods for Valentine’s Day We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan

We deeply regret going into this tunnel on our walk in the mountains of Japan Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home

Studio Ghibli releases Kodama forest spirits from Princess Mononoke to light up your home Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid

Major Japanese hotel chain says reservations via overseas booking sites may not be valid Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】

Put sesame oil in your coffee? Japanese maker says it’s the best way to start your day【Taste test】 No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says

No more using real katana for tourism activities, Japan’s National Police Agency says Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita

Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita Why is the Japanese kanji for “four” so frustratingly weird?

Why is the Japanese kanji for “four” so frustratingly weird? One simple kanji character in super-simple Japanese sentence has five different pronunciations

One simple kanji character in super-simple Japanese sentence has five different pronunciations Struggling with Japanese? Let Tako lend you a hand…or five

Struggling with Japanese? Let Tako lend you a hand…or five How to write “sakura” in Japanese (and why it’s written that way)

How to write “sakura” in Japanese (and why it’s written that way) Test your knowledge of Japanese convenience stores with this katakana puzzle

Test your knowledge of Japanese convenience stores with this katakana puzzle Busty Japanese brushstroke calligraphy artist shares visual appeal in video series【Videos】

Busty Japanese brushstroke calligraphy artist shares visual appeal in video series【Videos】 Yahoo! Japan finds most alphabetic and katakana words Japanese people want to find out about

Yahoo! Japan finds most alphabetic and katakana words Japanese people want to find out about Tried-and-tested ways to learn Japanese while having fun!

Tried-and-tested ways to learn Japanese while having fun! Why are some types of Japanese rice written with completely different types of Japanese writing?

Why are some types of Japanese rice written with completely different types of Japanese writing? Six (and a half) essential resources for learning Japanese

Six (and a half) essential resources for learning Japanese Twitter users say Japanese Prime Minister’s name is hiding in the kanji for Japan’s new era name

Twitter users say Japanese Prime Minister’s name is hiding in the kanji for Japan’s new era name What does a kanji with 12 “kuchi” radicals mean? A look at weird, forgotten Japanese characters

What does a kanji with 12 “kuchi” radicals mean? A look at weird, forgotten Japanese characters “We wasted so much time in English class” — Japanese Twitter user points out major teaching flaw

“We wasted so much time in English class” — Japanese Twitter user points out major teaching flaw How to speak Japanese like a gyaru【2024 edition】

How to speak Japanese like a gyaru【2024 edition】